undue process - Human Rights Watch

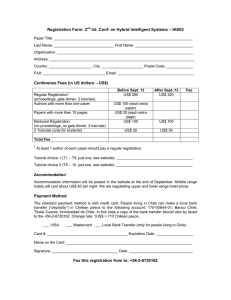

Anuncio