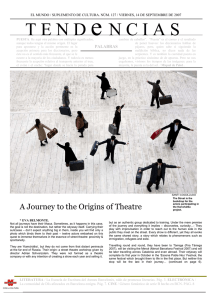

The Musical Theatre as a Vehicle of Learning: an

Anuncio