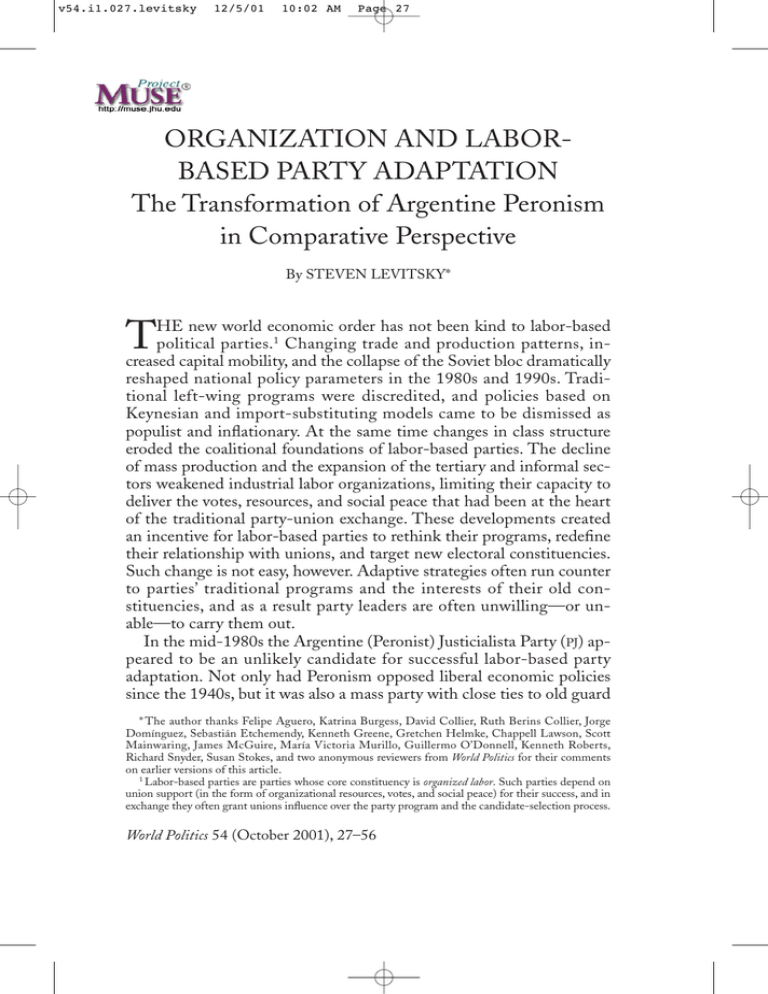

ORGANIZATION AND LABOR- BASED PARTY ADAPTATION The

Anuncio