Lynching in Guatemala Legacy of War and Impunity

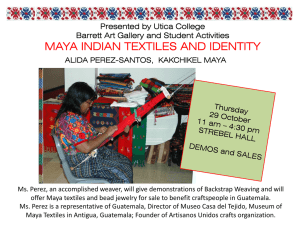

Anuncio