The prevalence, correlates and treatment of pain in

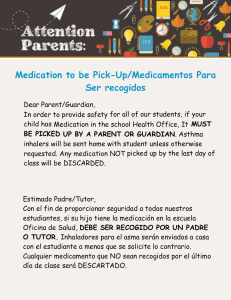

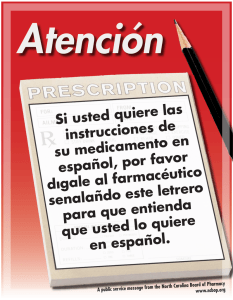

Anuncio