Fidel Fajardo-Acosta, "The King is Dead, Long Live

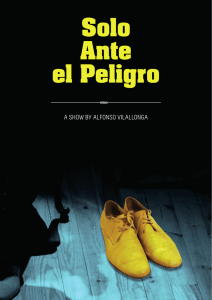

Anuncio