Lopadusa: an elusive mint*

Anuncio

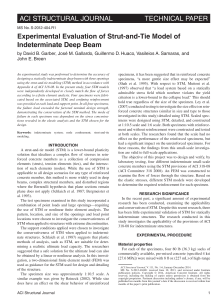

FABRIZIO ROSSINI Lopadusa: an elusive mint* In Africo maris, non procul a Thapso, iacet ignobilis insula quam Plinius longam VI miles dicit. Ab una parte Iouis caput, ab altera piscis. Ludovicus Nonnius, 1618 Introduction The greek Lopadousa, today Lampedusa, is a flat barren island, deeply set in the Mediterranean sea lying 120 km south of the coast of Sicily and only 70 km north of Tunis. Early mentions of the island are reported by Tolomeus, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, Livy and Ovidius. Lopadusa has a documented history going back to the Bronze Age, it was colonized by the Greek, experienced Punic influence for a long time and was conquered by the Romans who used the small island as a strategic naval base in their operations against the Carthaginians. The tiny and unassuming island has produced one of the lesser known bronze coinage of the entire Sicily and Magna Graecia series. The only known coin-type bears on the obverse a bearded head, probably Zeus, and on the reverse a tuna-fish with the island’s ethnicon in greek characters. Literary evidence It is peculiar that the Lopadusa coinage had been known as early as the late XVI century. The very first evidence that has been possible to assess, concerning this coinage, comes from a thesaurus written by XVI century engraver, publisher and humanist Hubertus Goltzius (1526-1583). The book1, the last one he published in Antwerp during his lifetime, is a reference book of ancient monumenta, namely marble inscriptions and coins, which had been either directly examined or collected by Goltzius. Under the list of cities and peoples cited we find the entry “Lopadoussaion”, in greek letters and next to it the abbreviation “num.” which stands for numismatum monumentis2, the book contains no plates or drawings. A few years before, in 1576, Goltzius had published the first part of his work devoted to Greek coinage3, the sequel to this work, dealing with the coins of continental Greece and its islands (among which Lopadusa coinage was to be included), was, however, published only after his death, by Jacob de Bie4, in 1618, who apparently used only the coin plates that Goltzius had already engraved, but not his text manuscript5, today at the Plantin-Moretus Museum, which is still unpublished6. The commentary to the plates was provided by Ludovicus Nonnius (Luis Nunnez), a physician and an antiquarian active in Bruges at the onset of the XVII century. Nonnius provides a very short description of the island and of the coin (cited above), whose engraved image appears, for the first time, on plate XVIII (nº 1) of this work. This first illustration is very important because it will be published, identical, for more than four hundred years, by all subsequent authors who have treated Lopadusa coinage (as no other example of the issue had, in the meanwhile, surfaced), until Calciati (see below) finally produced the first picture of a Lopadusa coin. Goltzius * 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 369 I am very much indebted to Christian Dekesel for his invaluable assistance in locating, checking and interpreting for me long forgotten manuscripts, as well as to my friends Alberto Campana and NS for their intelligent suggestions that helped me filling some gaps in the history of Lopadusa coinage. Goltzius, H.: Thesaurus Rei Antiquariæ Huberrimus, Antwerp, 1579 ibidem, Index XVII Regionum, Populorum, Opidorum, Fluviorum Nomina Alia Chorografica, pag. 138 Goltzius, H.: Sicilia et Magna Græcia, Brugis Flandrorum, 1576 Goltzius, H.: Græciæ Eiusque Insularum et Asiæ Minoris Nomismata ab Huberto Goltzio quondam Sculpta, Ludovici Nonni Commentario Illustrata, Antwerp 1618 Goltzius, H.: Historiæ Urbium et Populorum Insulæ Græciæ, 2 volumes, Antwerp, Plantin Moretus Museum, Manuscript M 156 I & M 156 II In the manuscript Goltzius describes extensively the island of Lopadusa but, apparently, makes no reference to its coinage. FABRIZIO ROSSINI had probably been the first and only one to actually see the coin and certainly the first to write on it, though we have no sure clue where he could have seen it. size and with only the first four letters of the island’s name visible, notwithstanding the supposedly poor conditions the coin-type is definitely that of Lopadusa. From the documentation we have left we know that Goltzius had travelled extensively to see collections all across Europe. We have an accomplished list7 of the collections he can have possibly visited during his grand tour that lasted two years (1558-1560). In the section concerning Italian collections, though, names stop little south of Naples and he seems never to have set foot in Sicily where, most logically, he might have seen the coin either in some private collections or on the antiquarian market. Torremuzza expresses extreme satisfaction for having managed to find a specimen of the rare coinage. The coin described in his work is particularly important since it appears to be the second known specimen of Lopadusa at that time. Spanheim8, in 1671, is the second author to make reference to Lopadusa. In his dissertatio quarta dedicated to the animals depicted on coins, he describes the piece citing the same coin plate number of the Goltzius/Nonnius work. He relates that Goltzius had been the first to see the coin and that Nonnius, in its commentary, does not mention which type of fish is represented on the coin’s reverse. The fish is unmistakably a tuna, very abundant in that portion of the Mediterranean sea. The drawing reported by Spanheim shows only the reverse of the coin with the fish looking left instead of the correct right (very probably a print error). Also the coin’s legend is identical to the Goltzius plate engraving. In 1755 the coin is mentioned by Gessnerus9, in his main work that is basically an atlas of all the ancient coin types known at that time, with no written commentary. Gessnerus illustrates the coin providing references to both Goltzius and Spanheim works, correctly indicating the plate number and page references for each source. Prince of Torremuzza10, mentions and illustrates the coin, first in his main work published in 1781. At the beginning Torremuzza doubts the existence of the piece, not having confidence in Goltzius, but since the coin had been described also by Spanheim and Gessnerus, he thought appropriate to make a reference to it anyway, and to publish an engraving identical to the archetypal type originally reported by Goltzius/Nonnius. In his first Addenda11, however, published in 1789, he recounts to have finally seen and bought a specimen of the coin. The specimen illustrated looks quite small in The last ancient author to mention Lopadusa coins is Eckhel12, who, in his Doctrina, again reiterates that nobody, except Goltzius, had seen any specimen of that coinage. After Eckhel for more than a 150 years no author apparently makes reference to the island’s coinage. All the main authors who wrote on Greek and Sicilian numismatics (Sambon, Head, Babelon, Gardner, Salinas, Rizzo, Gabrici, Kraay etc.) remain silent not only about the coinage but even failing to mention the island. In addition, all the published catalogues and Sylloges of major public and private collections of greek coins make no reference at all to the mint of Lopadusa. After a fleeting, almost oblivious mention by Cirami13, in 1959, who just reports the usual coin’s description giving a line-drawing illustration of, once more, the original Goltzius engraving, we have to wait until 1979, when Miní14 provides description and weights, but no pictures, of the first new specimens appeared since the XVIII century. Miní describes two coin types, the first (n. 1), which we know, with the bearded head to the right, for which he gives the Torremuzza reference and provides three weights that, however, do not match at all with those of the specimens we know today. 7. Beuther, M.: Calendarium Historicum, Frankfurt am Main, David Zephel, 1557. (Royal Library Albert I Brussels, II 38334), with a mention of nearly 800 collections. 8. Spanheim, E.: Dissertationes de Præstantia et usu Numismatum Antiquorum, Amsterdam 1671, page 231 9. Gessnerus, Joh. Jacobus,: Numismata Græca Populorum et Urbium, Ulm 1755, Plate 26, nº 10 10. Torremuzza, Gabriele Lancillotto Principe di, Siciliæ Populorum et Urbium Regum quoque et Tyrannorum Veteres Nummi Saracenorum Epocham Antecedentes, Palermo 1781, page 93, plate XCV 11. Torremuzza, Gabriele Lancillotto Principe di, Auctarium I, Palermo 1789, page 19 pl. VIII. 12. Eckel, I.: Doctrina Numorum Veterum, Wien 1792, Vol. 1 page 269-270 13. Cirami, G.: La Monetazione Greca della Sicilia Antica, Bologna 1959, pag.29, pl. 87 14. Miní, A.: Monete di Bronzo della Sicilia Antica, Palermo 1979, pag 496, nº 1; nº 1a 370 LOPADUSA: AN ELUSIVE MINT The second coin type (n. 1a) is described as showing the bearded head looking left. Again, no pictures are supplied and three different weights are provided. It looks quite unusual that although he terms the coins reported as “collezione privata”, a mention he often employs to make reference to specimens coming from his own collection, he does not supply pictures for any of them. The most recent author to mention Lopadusa coins is Calciati15 who, in his work on Sicilian bronze coinage of 1983 cites two types. The usual one with the head to the right, and the Miní supposed variant with the head to the left. Calciati gives pictures only of two specimens of the first type (for the second of these, n.1/1, he gives an incorrect weight) and also cites three more specimens known to Miní (one of these has the same weight, gr. 4.11 as the specimen he illustrates, presumably being the same coin). For the second type he cites the three Miní specimens pari passu including the same weights quoted by Miní, but no pictures, again, are shown. Incidentally, since three of the weights quoted by Miní are absurdly low and do not match with any of the specimens found so far, one would be brought to think that the Miní specimens are either the specimens we know with incorrectly reported weights or altogether (head-to-the-left type) non existent. Description of coin types and known specimens So far, six original bronze coins can be unmistakeably attributed to the mint of Lopadusa. Three specimens, which share the same style and belong to the same issue, possibly coming from the same hoard, had already been known, two of these described and illustrated by Calciati. Three other specimens belong to a slightly different, possibly later, issue and had not been known before. 1. First Type D/= Bearded and laureate male head, probably Zeus, to the right, hair and beard long and flowing down to the neck R/= Tuna-fish looking right, with legend above and under fish: LOPADOUS - SAIWN AE gr. 6.112 – 4.112 References: Goltzius (1618) pl. XXVIII, nº 1; Torremuzza, Auctarium (1789), pl.VIII; Cirami (1959) pl.87; Miní (1979), pag. 496, nº 1; Calciati (1983), Vol. III, pag. 368-370, n. 1, 1/1 The known specimens of this issue are (Plate 1, types 1.a - 1.c): 1.a gr. 6.112 Formerly Coll. M.; sold at Bank Leu, auction 79, Ø cm. 2.25 31st October 2000, lot n. 452. Unpublished. 1.b gr. 4.668 Legend incomplete. Formerly Coll. C.; Ø cm. 1.91 [Calciati, vol.III, pag. 369, n. 1/1]. 1.c gr. 4.112 Formerly Coll. C.; sold at Numismatica Ars Classica, Ø cm. 1.84 17th May 2001, lot n. 140. [Calciati, vol. III, pag. 369, n. 1] On the obverse a bearded and laureate head of Zeus is represented. The head has a straight nose, deep-set eyes and fine, narrow, lips. Hair and beard are long, wavy, and flowing down to the neck. On the reverse a tuna fish of full rounded flat shape is represented. Several other coins circulating in the Mediterranean basin show the tuna-fish type, though usually in the other issues the fish are normally two and of a more elongated shape (cfr. Solous and some Punic mints, like Gadez, etc.). The letters of the legend are small, squarish, wide-spaced, and quite different from other contemporary greek legends. The three coins illustrated, share the same reverse die as clearly shown by the examination of the letters of the legend. We have evidence that the two lighter specimens come from a small hoard that was found on the island in the years 1946-1948. From the very scant information that we have been able to trace back, we know that they were found when ploughing a cultivated field at the foot of the only small hill of the island. The hoard probably contained other coins, but unfortunately we totally ignore what they were. We only know for sure that no coins bearing the little 15. Calciati, R.: Corpus Nummorum Siculorum, Mortara 1983, vol. III pag. 368-370, nº 1, 1/1, 2 371 FABRIZIO ROSSINI crab, a type often attributed to the island, were present in the hoard. We would be inclined to believe that the specimens with the crab and punic characters are more likely to have been minted by nearby islands, or possibly Motya, under Punic rule, rather than by Lopadusa. Originally, the two lighter coins were sold by the heirs of the land’s owner to a small collector from whom they subsequently passed into a private collection of bronze coins. Although we lack formal evidence, we believe that in all probability also the heavier specimen may come from the same hoard. 2. Second Type D/= Bearded and diademed male head, probably of Zeus; Diadem, at the top of the head, is surmounted by a lotus flower (?) R/= Tuna-fish looking right, with legend above and under fish: LOPADOUS - SAIWN AE Zeus-Serapis found on the coins of Menai or Syracuse of the Roman period. The features of the head, if confronted with those of the first issue show a coarser, less refined style. The regular, straight, features of the god’s head in the first issue (look in particular at 1.c) are gone leaving place to thicker traits, the eye is globular, the nose large and the lips fleshy. The beard is no longer flowing but forms rather undistinguished short curly flocks, bulging the cheeks. On the reverse, the tuna appears more elongated and thicker than the the more rounded and flattish shape of the other issue. The shape of the legend’s lettering is also slightly different, although the truncation takes place at exactly the same letter. Finally, the flan of this issue is considerably narrower and thicker, consequently, though these specimens appear rather smaller, their weights are much the same as those of the other issue. The weights equivalence would suggest a close temporal proximity in the minting of the two series. On the other hand, the resort to a narrower, thicker flan, easier to prepare than a fully broad, flat one, would imply a more hasty preparation for their minting, which may as well explain the less refined features of this issue. gr. 6.140 - 4.062 References: This type does not seem to be known to the authors who had previously treated Lopadusa coinage, and is seemingly unpublished. The specimens, so far known, belonging to this issue, are (Plate 1, types 2.a - 2.c): 2.a gr. 6.140 The coin was part of a small hoard, located at the foot of a hill, whose composition appears to have contained some fractional bronze coins of Lipari (type with Ephestos and dolphin), eight silver litrae of Ziz, and other no better specified punic small bronzes. The presence of these coins, again if correctly reported, is also of extreme interest since it constitutes the first evidence for a tentative dating, at least, for the second issue of this coinage. Recent Contessa Entellina find. Unpublished. Ø cm. 1.80 2.b gr. 4.695 2002 Contessa Entellina find. Unpublished. Ø cm. 1.70 2.c gr. 4.062 The provenance of the heavier specimen (2.a) is from a recent hoard found in the proximity of Contessa Entellina, probably the original location of ancient Entella, 80 km. south of Palermo. If the reported news is correct, this, together with the next piece (2.b) would be the first testimonial of the circulation of Lopadusa coins beyond their island of origin. 1999-2000 unspecified find. Unpublished. Ø cm. 1.65 These three specimens clearly belong to a different issue. The Zeus head is no longer laureate but shows a diadem with two small protuberances at its top which may perhaps be a lotus flower, suggesting a similitude of the head with the representation of More scant information is available about the other two, lighter, coins. Specimen 2.b comes from an isolated find (circa 2002) again in the proximity of Contessa Entellina, albeit from a different location than the preceding specimen. Further investigation should be devoted to the underpinnings for the presence of two specimens of such rare issue in this particular location. Coin 2.c is also from a recent find (ca. 1999/2000), 372 LOPADUSA: AN ELUSIVE MINT possibly located in North-western Sicilian mainland, on which, however, no other information, at present, has unfortunately been possible to collect. As for the approximate dating of this issue the only hoard, albeit incomplete, evidence we have would suggest a dating around the IV century BC, supported by the Ziz litrae and not contradicted by the Lipari bronzes, also present in the hoard, whose production extended well into the fourth century as well. In addition to these specimens whose whereabouts are today known, we have sure evidence of two more pieces, as we have seen from the sources examined. The first is the original specimen seen and, most probably, bought by Goltzius, either for his own or possibly for the collection of Marcus Laurinus, a nobleman form Bruges for whom Goltzius often acted as an agent. Such provenance would have suggested a possible Belgian location for the coin today, however, a check with the principal Belgian public collections did not confirm the presence of a Lopadusa specimen. Moreover, the Marcus Laurinus collection was stolen in antiquity and probably dispersed in England. Again, a search through all major British public collections, as well as, incidentally, all other major European ones, did not produce any results. The second specimen mentioned by the literature is the one described and purchased by Torremuzza (see above). The Prince’s collection knew an early dispersal into many different streams. A portion of it going to enrich the funds of what will become the coin cabinet of the Archeological Museum of Palermo. Another portion was sold to the Hunter collection, today at the Glasgow Museum; others to Lord Northwick and, finally, some portions were dispersed into several major and minor Sicilian private collections. All the checks made to verify the presence of the Lopadusa specimen, owned by Torremuzza, in the above mentioned public collections have so far yielded negative results16. It has, however, been possible to verify only a few private collections. At some point, other specimens have been claimed to be around at different locations. One had been reported at the Museum of Catanzaro, in Calabria. A thorough check with the curators of the collection, which has recently been entirely catalogued, has proved the statement inaccurate. Another specimen was claimed to be housed in the collection of Prof. Pugliatti of Messina. But Consolo-Langher, who has published the Pugliatti collection, does not report the piece17. Further investigation with the regional archeological Museum of Messina, where Prof. Pugliatti resided, did not produce any more evidence. Finally, we have received credible evidence that two more specimens, in rather poor conditions, had appeared on the antiquarian market in the late Seventies, possibly coming from a contemporary hoard, which has not been possible to locate so far. All in all, evidence has been ascertained for the existence of up to ten specimens, six of which have been possible to trace back and properly describe. Conclusions The only issue attributed with certainty to the island of Lopadusa confirms its character of rarity and obscure origin. The very few specimens survived and the scant information remained shed but little light on the issue’s history. Some of these coins’ elements may suggest a possible stylistic influence derived by the punic environment, as the island remained under Punic dominance for an extended period of time. However, the issue bears a distinct greek character that may conflict with the proposed dating placed between the 3rd and the 2nd centuries BC, under Roman rule18. The only hoard evidence so far retraced would support a dating anticipated to the IV century. Other Sicilian issues bearing the tuna-fish type are those of Solous19 also from the IV century, though the Lopadusa tuna looks more refined in style and detailed than the Solous representations, which in addition bear punic letters, not greek ones. 16. We would like to express our thanks, for their prompt and factual cooperation, to the curators and senior officers of the Soprintendenze and Archeological Museums of : Palermo, Trapani Agrigento, Siracusa, Catania, Messina, Reggio Calabria, Catanzaro, Crotone, Vibo Valentia, Milano, Padova, Bologna, Napoli, Roma. 17. Consolo-Langher, S.: Contributo alla Storia dell’Antica Moneta Bronzea in Sicilia, Milano, 1964 18. See Walker, Bank Leu Auktion 79, Zurich, 31-10-2000, description of lot 452 and Calciati (cit.) vol. III p. 368 19. See Calciati (cit.) Vol. I, nnº 11-12 and especially nº 15, dated by Calciati at 300-241 BC. See also Campana, A.: Corpus Nummorum Antiquæ Italiæ, CNAI, nº 20, dated by Calciati at 330-260 BC. 373 FABRIZIO ROSSINI The lettering utilized for the ethnicon is also puzzling as the irregular size, wide spacing, and squarish shape employed for its characters (in particular the “L”, “S” and the “N”), finds few parallels in the Sicilian series20. The mint , which was very probably situated on the island, could have been located close to the island’s natural harbour of Le Saline, thence the tuna-fish on the reverse of the coin. Tuna fishing and commerce had been popular for centuries in Sicily, as testified, for instance, by the delightful representation of the tuna seller on the Mandralisca crater (fig. 1) in the Cefalú museum. Incidentally, the tuna at the fisherman’s stall looks impressively similar to the fish shown on the first issue of Lopadusa. The minting must have been extremely limited in time and also in quantity, as is testified by the fact that the three known specimens of the first issue all share the same reverse die. And the three known pieces of the second issue also appear to share same obverse and reverse dies. The motives that led the tiny Lopadusa to mint these bronze coins can only be surmised. Almost certainly, the need for exchange currency did not justify the issue, as was amply satisfied by other contemporary currencies that circulated on the island. More imaginatively, we like to suppose that the crave for resurgence and self-determination of the small Sicilian city centers ensuing in the Timoleontian aftermath, might have provided the appropriate fertile ground to support the flourishing of small local mints that concentrated on a small bronze output as a means to voice their own self-determination. It is to be hoped that the excavations presently undergoing on the island, under the direction of Soprintendenza Archeologica di Agrigento, may bring in some new elements that will permit to better understand the historical implications and to help placing an appropriate dating for this intriguing issue. 20. Some bronze coins of Agyrion (Calciati, cit., vol. III, pag. 115 ss.) show legends which bear a faint resemblance to the Lopadusa legend’s characters. 374 LOPADUSA: AN ELUSIVE MINT 1a 1b 1c 2a 2b Fig. 1 2c 375