Biblical evidence from Obadiah and Psalm 137

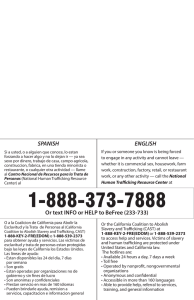

Anuncio