THE SPANISH PRONOUN SYSTEM I. Subject Pronouns

Anuncio

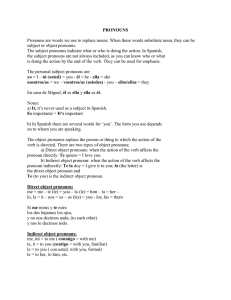

APPENDIX 1: THE SPANISH PRONOUN SYSTEM One of the most complicated aspects of grammar for learners of Spanish is the pronoun system. Subject pronouns, direct object pronouns, indirect object pronouns, reflexives —students very often end up with a “mish mash” of pronouns, trying to use se to mean he, me as a subject pronoun, and so on. The special grammar supplements here are meant to help give students a greater understanding of pronouns than they would have with typical textbook presentations. I. Subject Pronouns A. The notion of “subject” is a grammatical notion and refers to the relationship between a noun (boy, John, dogs) or a noun “phrase” (the boy, the happy boy, all of those dogs) and a verb. Generally, the subject answers the question Who or What VERBs? or Who or What is VERBing?as in Who or What eats? Who or What is looking? The man is smiling. The green houses are for sale. Who is smiling? The man. (So, the man = subject.) What is for sale? The green houses. (So, The green houses = subject.) B. A pronoun refers to a small word that stands in place of a noun or noun phrase, especially when the speakers already know who or what is being talked about. Let’s take the example, John is a responsible student. He studies every day. In the second sentence, he is a pronoun that stands for John, who is already mentioned in the sentence before. Pronouns are used to avoid redundancy. Look how awkward the following would be spoken aloud: Jaime knows a lot about wines. Jaime drinks them all the time. Jaime lived in Napa and Jaime has also worked in a winery. We use the subject pronoun he to avoid the repetition. C. The subject pronouns that stand for other nouns in English are he, she, it, and they. CORRESPONDING SAMPLE SUBJECTS SUBJECT PRONOUN John, the boy, the dog, Mr. Smith Mary, my aunt, the ugly witch the book, the time, the big white house John and Mary, the kids, the big dogs he she it they We also call I, you, and we subject pronouns because they stand for us. For example, if your name is Bill you don’t say, Bill went to the store yesterday. You say, I went to the store yesterday. If you are talking to your friend Sally, you don’t say, Does Sally want to come? You say, Do you want to come? So, in a sense, these pronouns stand for names of people who are involved in the conversation. The entire set of subject pronouns in English then are the following, along with their Spanish equivalents. I you you he, she yo tú usted (Ud.) él, ella we you you they nosotros/as vosotros/as ustedes (Uds.) ellos/ellas Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 345 The English pronoun it does not have a Spanish equivalent; no pronoun is used in sentences such as the following. Este libro es bueno, pero cuesta mucho. This book is good, but it costs a lot. In the sentence, the verb cuesta includes the idea of it as a subject. D. Remember that subject pronouns in general are omitted in Spanish when the person or thing referred to is clearly understood. Hablo español. Jaime es bilingüe: habla inglés y español. (No need to add yo because the verb form hablo tells us who speaks Spanish.) (No need to add él. The verb form habla encodes that information as well as ella and usted. However the context of the sentence makes it clear that Jaime/él is the only logical subject.) E. Self-test on Subject Pronouns 1. Using the question Who or What VERBs? or Who or What is VERBing? determine the subject of each sentence. a. Michael has a cold. b. Amy and John have broken up. c. Two big brown dogs attacked a man on the street. d. I refuse to believe you. 2. Continue each “story” using the correct subject pronoun. a. Michael has a cold. took some medicine and now b. Amy and John have broken up. c. 3. are not speaking to each other. Two big brown dogs attacked a man on the street. d. I refuse to believe you. feels better. mauled him in front of witnesses. am not that gullible. Using the same technique as in item 1, identify the subject in each sentence in Spanish. a. María es profesora. b. Mis amigos no hablan español. c. Todos en la clase estudiamos español. d. Tomo mucho vino. 4. Why does the following series of sentences sound unnatural in Spanish? Mis amigos no hablan español. Ellos hablan francés. Ellos son de Quebec. Answers 1. a. Michael b. Amy and John c. two big brown dogs d. I 2. a. He, he b. They c. They d. I 3. a. María b. mis amigos c. todos en la clase d. yo (Did you remember that Spanish does not need to use subject pronouns? For this item, you ask, Who drinks (a lot of wine)? The answer is I.) 4. Because, unlike English, Spanish omits subject pronouns when the subject of the sentence is clear. The use of ellos is unnecessary and sounds like English, not Spanish. 346 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System II. Direct Objects and Direct Object Pronouns A. Direct object is a grammatical notion and, like subject, refers to the relationship between a noun (boy, John, dogs) or a noun phrase (the boy, the happy boy, all of those dogs) and a verb. However, unlike subjects, the question you ask to determine the direct object of a verb is Who or What is VERBed? or Who or What is being VERBed? Robert respects his professor. The dog really hates baths. Jaime knows wines well. Who is respected? His professor. (So, his professor = direct object.) What is hated? Baths. (So, baths = direct object.) What is known well? Wines. (So, wines = direct object.) B. As you may recall from your study of subjects and subject pronouns, a pronoun refers to a small word that stands in place of a noun or noun phrase, especially when the speakers already know who or what is being talked about. Let’s take the example, Jaime knows wines well. He drinks them all the time. In the second sentence, them is a pronoun that stands for wines, something that is mentioned in the sentence before. Pronouns are used to avoid redundancy. Look how awkward the following would be spoken aloud: Jaime knows a lot about wines. He drinks wines all the time. He used to sell wines. We use the direct object pronoun them to avoid the repetition of the word wines. Now, try the same with the following. What word would you use to replace María? Jaime meets María in the park. He follows María. He helps María with her books. You are right if you replaced the direct object noun María with the direct object pronoun her, as in the following. Jaime meets María in the park. He follows her. He helps her with her books. C. You already know that I is a subject in English, as are you and we. But what are their corresponding direct object pronouns? That is, what if I, you, and we are not subjects of verbs but direct objects of verbs? The corresponding pronouns are me, you, and us. Robert likes me. Who is liked? Me. (So, me = direct object.) I like Robert. Who is liked? Robert. (So, Robert = direct object.) We visit our parents. Our parents visit us. Who is visited? Our parents. (So, our parents = direct object.) Who is visited? Us. (So, us = direct object.) Here is the list of English direct object pronouns. Remember, to identify an object, you normally ask, Who or What is VERBed? or Who or What is being VERBed? me you him her it us you them John knows me well. John knows you well. John knows him well. John knows her well. John knows it well. John knows us well. John knows you well. John knows them well. Note that only it and you can be both objects and subjects. You ate my pie. I hate you! It’s on the floor. I ate it. Who ate my pie? You. (So, you = subject.) Who is hated? You. (So, you = object.) What is on the floor? It. (So, it = subject.) What was eaten? It. (So, it = object.) Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 347 D. Spanish has direct object pronouns just like English and they have pretty much the same function: to avoid repetition. Let’s take the Jaime example with wines again: Jaime knows a lot about wines. He drinks wines all the time. He used to sell wines. We avoid repeating the direct object noun, wines, by using a direct object pronoun, them: Jaime knows a lot about wines. He drinks them all the time. He used to sell them. In Spanish, we would do something similar, except that direct object pronouns must be placed in front of conjugated verbs (that is, verbs with endings that show the subject): Jaime conoce bien los vinos. Bebe los vinos mucho. Vendía los vinos. → Jaime conoce bien los vinos. Los bebe mucho. Los vendía. So, literally, you are saying, Them (he) drinks all the time. Them (he) used to sell. Remember the example about Jaime and María from section B? Here it is again, in English followed by the equivalent in Spanish. Jaime meets María in the park. He follows María. He helps María with her books. Jaime conoce a* María en el parque. Sigue a María. Ayuda a María con sus libros. (Note how the subject pronoun él is omitted because we know what the subject of sigue and ayuda is.) So, how would this look in Spanish? The direct object pronoun that would replace María, a feminine, singular noun, is la. Jaime conoce a María en el parque. La sigue. La ayuda. After the first sentence, which introduces Jaime as the subject and María as the direct object, what you literally say is, Her (he) follows (he is understood). Her (he) helps (he is understood). Here is a quick summary of the main points for direct objects and direct object pronouns so far. 1. 2. 3. A direct object refers to a noun or noun phrase that answers the question Who or What is VERBed?, Who or What is being VERBed? A direct object pronoun is a small word that replaces a direct object noun when we know who or what is being talked about. In Spanish, direct object pronouns go in front of conjugated verbs. In English, they go after. E. Now, here is the list of English and Spanish direct object pronouns with examples. ENGLISH SPANISH me: John knows me. me: Juan me conoce. you: John knows you. te: Juan te conoce. him: John knows him. lo: Juan lo conoce. her: John knows her. la: Juan la conoce. it: John knows it. lo/la†: Juan lo conoce. us: John knows us. nos: Juan nos conoce. you: John knows you (the two of you). os: Juan os conoce. los/las†: Juan los conoce. them: John knows them. los/las†: Juan los conoce. *This a does not mean to. Instead, it is what we call the object marker a. It has no English equivalent. You will learn about it later. † Remember that these pronouns can refer to masculine (lo, los), feminine (la, las) or a mixed group (los). For example, if we’re talking about a book: Es un buen libro; Juan lo conoce. If we’re talking about a novel: Es una buena novela; Juan la conoce. 348 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System F. Self-test On Direct Objects and Direct Object Pronouns 1. Using the question Who or What is VERBed?, identify the direct objects in each sentence in English and Spanish. a. The dog chases cats. b. My aunts and uncles visit my mother all the time. c. Cathy admires her brother very much. d. El profesor conoce bien a sus estudiantes. 2. e. Mi hermana toma café mucho. f. Jaime encuentra la tarjeta de María. Continue each “story” in English using the correct direct object pronoun. a. The dog chases cats. In general, he hates . b. My aunts and uncles visit my mother all the time. They always call she’s home. c. 3. Cathy admires her brother very much. In fact, she puts first to make sure on a pedestal. Continue each “story” in Spanish using the correct direct object pronoun. Remember that the subject will not be expressed in the second sentence and is understood from the verb! a. El profesor conoce a sus estudiantes. Claro, b. Mi hermana toma café mucho. c. ve todos los días en clase. prepara al estilo italiano, con mucha leche. Jaime encuentra la tarjeta de María. Al final, Answers 1. a cats c. her brother b. my mother d. sus estudiantes 2. a. them b. her c. him 3. a. los b. Lo c. la guarda. e. f. café la tarjeta de María III. The Object Marker a A. Spanish uses the little word a to mark object nouns and noun phrases when both the subject and object are theoretically capable of performing the action expressed by the verb. Let’s take the example of to know in the following sentences. Jaime conoce a María. Jaime conoce los vinos. In the first example, both Jaime and María are capable of performing the act of knowing. Thus, we mark María with the object marker a to be sure everyone knows we mean she is the object of the verb and not the subject. However, in the second, wines are not animate things capable of performing the act of knowing, hence no a is needed to mark wines as the object of the verb. See if you can explain the use and non-use of a as object marker in these two sentences. La señora ve a su hija. La señora ve la televisión. Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 349 You are right if you said that in the first example, both the woman and her daughter presumably are capable of the act of seeing. So, the daughter (su hija) is preceded by a to indicate she is the object and not the subject. But televisions don’t have sight and hence can’t see. Thus, no a is needed in the second example. You might wonder why the a is even necessary if the subject always comes before the verb and the object after. We will see why in the section on word order. B. Self-test on Object Marker a 1. Complete each sentence twice, using each object. Insert an a where necessary. Mario espera... a. (el autobús, Jaime) b. El chico llama... (su profesora, el ascensor [elevator]) Jaime no comprende... c. la situación, el Sr. Rasser Answers 1. a. Mario espera el autobús. Mario espera a Jaime. b. El chico llama a su profesora. El chico llama el ascensor. c. Jaime no comprende la situación. Jaime no comprende al Sr. Rasser. IV. Word Order A. English is fairly rigid in its word order. That is, English uses almost exclusively subject-verb-object word order, as indicated by the following examples. Jaime knows wines. SUBJECT VERB OBJECT The three dogs are chasing my cats. SUBJECT VERB OBJECT Mario likes her. SUBJECT VERB OBJECT PRONOUN He hates children. SUBJECT PRONOUN VERB OBJECT B. Spanish, however, is less rigid in its word order. You have already seen subject-verb-object, subject-object-verb, and object-verb word orders. Jaime conoce los vinos. SUBJECT VERB OBJECT Jaime los toma mucho. SUBJECT OBJECT PRONOUN VERB PHRASE Los toma. OBJECT PRONOUN VERB Spanish makes frequent use of object-verb-subject word order as well. 350 Los toma Jaime. OBJECT PRONOUN VERB SUBJECT Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System C. Spanish can even put an object noun in front of the verb. This is where the a comes in handy. Note that when this happens, Spanish generally “copies” the function of the object by adding an object pronoun as well. (This is the one time when direct objects and direct object pronouns are redundant in a sentence.) A María la ve Jaime. OBJECT OBJECT PRONOUN VERB SUBJECT A Jaime lo ve María. OBJECT OBJECT PRONOUN VERB SUBJECT You will learn in your studies when such constructions are normally used. For now, it is enough to know they exist and when you see them, not to misinterpret them by thinking the first noun is the subject as in English! D. Self-test on Word Order in Spanish Remember the trick in Spanish is not to rely on English word order to make or interpret sentences. Determine which English equivalent is best for the italicized sentence in Spanish. 1. Jaime ve a María en el supermercado. La invita a tomar un café. a. He invites her for a coffee. b. She invites him for a coffee. 2. La señora quiere mucho a su perro. La acompaña a todas partes. a. She accompanies him everywhere. b. He accompanies her everywhere. 3. A su hermano no lo comprende Juan para nada. Pero, así son las relaciones familiares. a. His brother doesn’t understand Juan at all. b. Juan doesn’t understand his brother at all. Answers 1. a 2. b 3. b V. Indirect Objects and Indirect Object Pronouns A. Indirect objects involve yet another relationship between a noun and a verb. Recall that subjects answer the question Who or What VERBs (Who or What is VERBing)? and direct objects answer the question Who or What is VERBed (Who or What is being VERBed)? I told a secret to Mary. Who tells? I. (So, I = subject.) What is told? A secret. (So, a secret = direct object.) Indirect objects normally answer the question To whom or to what is X VERBed? (X refers to the direct object.) They can also answer the question For whom or for what is X VERBed? Let’s take the example from above. To whom is a secret told? Mary. So, Mary is the indirect object. Here’s the complete picture. I told a secret to Mary. Who tells? I. (So, I = subject.) What is told? A secret. (So, a secret = direct object.) To whom is a secret told? Mary. (So, Mary = indirect object.) Without looking ahead, try identifying the subject, direct object, and indirect object in the following sentence: The dog brought his ball to me. Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 351 You are correct if your explanation looks similar to the following: The dog brought his ball to me. Who brings the ball? The dog. (So, the dog = subject.) What is brought? His ball. (So, his ball = direct object.) To whom is his ball brought? Me. (So, me = indirect object.) Try the same procedure but with a different sentence: The canaries are singing a sweet song for the cat. The canaries are singing a sweet song for the cat. Who or what sings? The canaries. (So, the canaries = subject.) What is sung? A sweet song. (So, a sweet song = direct object.) For whom is a sweet song sung? The cat. (So, the cat = indirect object.) B. There are two things to keep in mind with indirect objects. You may have noticed that with many verbs in English the standard word order seems to be subject-verb-direct object-indirect object. English, however, can reverse the order of the direct and indirect objects and eliminate the to or the for as in the following examples. Jerry fed tuna to his cat. Jerry fed his cat tuna. In both sentences, his cat remains the indirect object because it answers the question, To whom is the tuna fed? And, of course, tuna remains the direct object because it answers the question, What is fed? The second thing to keep in mind is that just because there is a to or a for in a sentence in English does not mean the noun that follows it is an indirect object. Some verbs in English require prepositions, for example, there is a difference between to look, to look at, and to look for. Thus, in the following sentence, you have to expand your questions to determine subject, direct object, and indirect object by linking for with the verb look. The dog is looking for bones for me. Who looks for something? The dog. (So, the dog = subject). What is looked for? Bones. (So, bones = direct object.) For whom are the bones looked for? Me. (So, me = indirect object.) Thus, only one noun with a for in front of it is the indirect object in the above sentence. C. As is the case for subjects and direct objects, indirect objects also have corresponding pronouns, little words that replace indirect objects when we know who or what is being talked about. The indirect object pronouns in English are: me, you, him, her, it, us, and them. As in the case with direct objects and direct object pronouns, only him, her, it, and them actually “replace” a noun once it is mentioned. Did you buy something for mother? Yes, I bought her some candy. (or I bought some candy for her.) In this sentence, her replaces mother to avoid redundancy. Try replacing the indirect object in the following “story” to avoid redundancy. I found a rock for Johnny. I gave it to Johnny and he was happy. Maybe tomorrow I’ll bring Johnny another present. If you applied everything you know so far, then your revision should look like this. I found a rock for Johnny. I gave it to him. Maybe tomorrow I’ll bring him another present. 352 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System By the way, did you notice how in the third sentence, we eliminated the to by reversing the order of direct and indirect objects? However, Johnny remained the indirect object. Have you noticed that indirect object pronouns can be side by side with direct object pronouns? You might think this would be confusing, but as a speaker of English you sort it all perfectly in your head. Remember, the difference between direct and indirect object pronouns are the questions they answer: Who or What is VERBed? and To whom or For whom is X VERBed? So, imagine a situation in which a person is a direct object and another person is an indirect object. You should be able to use the questions you’ve learned to determine which is which. The kidnapper brought him to me. The kidnapper brought me him. In this situation the questions go like this: Who brings something? The kidnapper. (So, the kidnapper = subject.) Who is brought? Him. (So, him = direct object.) To whom is he brought? Me. (So, me = indirect object.) D. Spanish is similar to English in that it has both indirect objects and indirect object pronouns. As in the case of English, in Spanish indirect objects and their pronouns answer the question To/For whom or To/For what is X VERBed? ENGLISH SPANISH me: John brings flowers to me. me: Juan me trae flores. you: John brings flowers to you. te: Juan te trae flores. le: Juan le trae flores. ( formal you, Ud.) him: John brings flowers to him. le: Juan le trae flores. her: John brings flowers to her. le: Juan le trae flores. us: John brings flowers to us. nos: Juan nos trae flores. you: John brings flowers to you. os: Juan os trae flores. les: Juan les trae flores. ( formal you, plural, Uds.) them: John brings flowers to them. les: Juan les trae flores. In Spanish, indirect objects are almost always marked by the preposition a, which is equivalent to both to and for in corresponding English sentences.* What is more, in Spanish indirect objects rarely occur without a corresponding indirect object pronoun, thus making Spanish redundant within a sentence. See how the indirect object su amigo and the indirect object pronoun le both appear in the same sentence below. Marcos le da muchos consejos a su amigo. Marcos gives a lot of advice to his friend. A redundant indirect object noun typically appears only with third-person indirect object pronouns (that is, when you’re talking about someone else—Mary, the dog, them). When you or the person or people you are talking to is the indirect object, then redundancy doesn’t normally occur. Marcos me da muchos consejos. Marcos gives a lot of advice to me. *You’ve learned that para means for and you’re right. But when it comes to indirect objects, a is the equivalent of English for. So, use a for indirect objects and para in other situations—until you learn something new! Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 353 Have you noticed that indirect object pronouns precede a conjugated verb (that is, a verb with an ending that shows the subject)? This is quite different from English, which places both indirect objects and their pronouns after verbs 100 percent of the time. E. Sometimes you need to add emphasis or clarify an indirect object pronoun. Spanish does this by adding a plus an appropriate pronoun (or noun). English would add vocal stress, making the word louder as in They’re not for YOU. or He’s giving them to ME. The following chart illustrates this. UNEMPHASIZED, NOT CLARIFIED EMPHASIZED OR CLARIFIED Juan me da buenos consejos. add a mí (note the accent mark) Pues, no sé cómo es la situación contigo pero Juan me da a mí buenos consejos. Juan te da buenos consejos. add a ti (no accent) Juan te da buenos consejos a ti pero a mí no. Juan le da buenos consejos. add a él, a ella, a Ud., a + noun No a ella. Juan le da a él buenos consejos. No a Julia. Juan le da a Gloria buenos consejos. Juan nos da buenos consejos. add a nosotros, a nosotras Bueno, Juan siempre nos da a nosotros buenos consejos. Juan os da buenos consejos. add a vosotros, a vosotras Juan os da mejores consejos a vosotros en comparación con los consejos que nos da a nosotros. Juan les da buenos consejos. add a ellos, a ella, a Ud., a + noun Sí, sí. Juan les da a Uds. buenos consejos mientras ni* nos habla a nosotros. Before continuing, let’s review indirect objects and indirect object pronouns. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Both English and Spanish indirect objects answer the question To whom or To what is X VERBed (is being VERBed)? Spanish only uses a to mark indirect objects, even when the English translation would use for or to. In Spanish, indirect object pronouns always precede conjugated verbs. Indirect object pronouns are often redundant, especially in third-person situations (when you’re talking about someone else). You can emphasize or clarify an indirect object pronoun by adding a plus the appropriate noun or pronoun. F. Self-test On Indirect Objects and Indirect Object Pronouns 1. For each sentence, identify the subject, direct object, and indirect object using the “test questions” that you know. a. The man donated money to the church. b. My aunt spins tall stories to anyone who will listen. c. I tell my friend everything that happens. d. El profesor nos da mucha tarea. e. El perro le ofrece (offers) su pata (paw) al señor. f. Le digo «sí» a mi mamá todo el tiempo. *When ni is used like this, the English equivalent is doesn’t even or not even as in, “He doesn’t even talk to us.” 354 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 2. Continue each “story” in English using the correct indirect object pronoun. a. The cat kills mice for Mary, his owner. He leaves them for on the doorstep. b. My aunts and uncles visit my grandfather all the time. They always bring clothing. c. 3. Susie thinks I’m good with secrets. She always says things to beyond us. gifts, usually , expecting them to not go Continue each “story” in Spanish using the correct indirect object pronoun. Remember that the subject may not be overtly expressed and is understood from the verb! a. El profesor es difícil con sus estudiantes. b. Veo a mi padre con frecuencia. Cuando visita = to pay a visit.) c. Cuando Jaime encuentra a María, da mucha tarea todos los días. hago visita, siempre está contento. (Note: hacer ofrece su tarjeta pero ella le dice: «Si quiere, la guarda.» Answers 1. a. S: the man, DO: money, IO: the church b. S: my aunt, DO: tall stories, IO: anyone who will listen c. S: I, DO: my friend, IO: everything that happens d. S: el profesor, DO: mucha tarea, IO: nos (nosotros) e. S: el perro, DO: su pata, IO: le (el señor) f. S: yo (understood), DO: sí, IO: mi mamá 2. a. her b. him c. me 3. a. Les b. le c. le G. Do Sentences Always Have Both Direct and Indirect Objects? From what you have seen so far, you may think sentences with indirect objects always have direct objects, too, as in The man donated money to the church. But this is not the case. Lots of times, verbs can be used without a direct object and with an indirect object only. Here are some examples in English. She told me. I spoke to him already. (she = subject, me = indirect object) (I = subject, him = indirect object) In Spanish, the most frequent verb that appears without a direct object and only an indirect object is hablar. Spanish is unlike English in that the verb decir and others, cannot appear without a direct object pronoun. I speak to him every day. She tells me things. She tells me. Le hablo todos los días. Me dice cosas. Me dice would be incorrect. As you learn more and more Spanish, you will see how verbs work in terms of direct and indirect objects. For now, you can always locate an indirect object by asking To whom or For whom is X VERBed? VI. Another Note about a Have you figured out that the tiny word a in Spanish has two meanings and two functions? One is as the preposition meaning to or for, which can indicate direction or mark indirect objects. Voy a la plaza. El perro le da besos a Juan. I’m going to the plaza. The dog gives kisses to John. (The dog gives John kisses.) Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 355 As you have seen in section III, a is also used to mark the direct object when both it and the subject are theoretically capable of performing the action or activity expressed by the verb. Mi mamá conoce al presidente. El presidente conoce a mi mamá. Mi mamá conoce San Francisco. My mother knows the president. The president knows my mother. My mother knows (is familiar with) San Francisco. El gato sigue al perro. El perro sigue al gato. El gato sigue la línea. The cat follows the dog. The dog follows the cat. The cat follows the line. Remember that because there is an a in the sentence doesn’t mean the word that follows it is automatically the direct object. Look at the following sentences and see if you can tell which nouns are the direct objects and which are the indirect objects. Remember to use the questions you have learned so far. Ramón no le habla a Paco mucho. El león mira a la señora con mucha atención. El doctor toca (touches) al paciente durante un examen. Enrique les compra a sus padres regalos turísticos. You were correct if you said the following. Ramón no le habla a Paco mucho. Paco is an indirect object because when I ask the question To whom is something spoken? the answer I get is Paco. There is no direct object in this sentence. (I know Ramón is saying something, speaking something, but it is not expressed.) El león mira a la señora con mucha atención. La señora must be the direct object because when I ask, Who or what is looked at? I get the answer the woman. There is no indirect object in this sentence. El doctor toca al paciente durante un examen. Paciente has to be the direct object because it does not answer the question To/For whom is (something) touched? but instead Who is touched? Enrique les compra a sus padres regalos turísticos. Padres has to be the indirect object because only it answers the question, For whom are the gifts bought? Regalos turísticos is the direct object because it answers the question Who or what is bought? VII. Gustar A. While English uses the verb like to express a certain relationship between two entities as in John likes Mary and John likes milk, Spanish has no such verb. Instead, Spanish frequently uses the verb gustar. This verb means something similar to to be pleasing, as in Mary is pleasing to John and The milk is pleasing to John. Note how there is an indirect object in each sentence: to John. With the verb like, John is the subject (Who likes?) but with the verb to be pleasing, John is the indirect object (To whom is Mary pleasing?). Likewise, the direct object of to like normally is the subject of to be pleasing in sentences with the same meaning. In the example, John likes milk, milk is the direct object (What is liked?) whereas in The milk is pleasing to John, milk is the subject (What is pleasing?). Before moving on, convert the following sentences from like in English to to be pleasing. TO LIKE 356 1. The dog likes the cat. 2. The dog likes to chase the cat. 3. The dog likes me. 4. The dog likes beans. Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System TO BE PLEASING You are correct if your to be pleasing sentences look like the following. 1. 2. 3. 4. The cat is pleasing to the dog. To chase the cat is pleasing to the dog. I am pleasing to the dog. Beans are pleasing to the dog. Did you notice in number 4 that you used the plural form of to be pleasing, that is, are pleasing and not the singular (is pleasing)? That’s because in item 4, when beans becomes the subject of to be pleasing, the verb has to agree with the subject and beans is a plural noun. B. As we mentioned, gustar works like to be pleasing. In each sentence there is something or someone doing the pleasing (the subject) and someone or something to whom that thing or person is pleasing (the indirect object). The typical sentence structure for gustar requires a + noun (the indirect object) followed by an indirect object pronoun, then the verb then the subject. This is exactly the reverse order from English to be pleasing. Note the differences below. (We are using IO to abbreviate indirect object.) A Juan a + IO le IO pronoun gusta Verb Milk Subject is pleasing Verb to John. to + IO la leche. Subject So, in most instances you can take English word order with to be pleasing, reverse it, and you have the basic sentence structure for gustar in Spanish (plus or minus a few words). Milk is pleasing to John. → To John is pleasing milk. A John le gusta la leche. Try reversing the word order in English of the following to be pleasing sentences and see if you can come up with the Spanish equivalents. For now, we’re keeping everything singular so you don’t have to worry about verb agreement and the correct indirect object pronoun. STANDARD ENGLISH REVERSE WORD ORDER SPANISH The dog is pleasing to Mary. Soup is pleasing to my mother. Cheese is not pleasing to our teacher. You would be correct if your sentences looked like this: STANDARD ENGLISH REVERSE WORD ORDER SPANISH The dog is pleasing to Mary. To Mary is pleasing the dog. A Mary le gusta el perro. Soup is pleasing to my mother. To my mother is pleasing soup. A mi mamá le gusta la sopa. Cheese is not pleasing to our teacher. To our teacher is not pleasing cheese. A nuestra profesora no le gusta el queso. The problem you may have is that if you think in English, the verb like is much more common than be pleasing. What you have to do is convert like sentences to be pleasing sentences. Then you can get to the correct Spanish structure. But don’t worry! You won’t do that for long. After you hear lots and lots of gustar sentences, you’ll get the hang of it and won’t have to think about it. Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 357 C. For the next two parts of section VII, we are going to assume you are familiar with indirect objects and indirect object pronouns. If you aren’t, you may wish to review those concepts. As you know, gustar requires not only a subject, but also an indirect object pronoun. When you are talking about someone else, it also requires a redundant indirect object noun phrase; this is not the case when talking about to me, to you, and to us. What this means is that the verb gustar has to agree with the subject and the indirect object pronoun has to agree with the indirect object. Look at the following examples, being sure to interpret them correctly. Do not misunderstand the sentences because you expect them to have subject-verb-object word order! A Juan le gusta el perro. verb: gusta, because el perro is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: le because Juan is the indirect object A Juan le gustan los perros. verb: gustan, because los perros is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: le because Juan is the indirect object A mi perro le gusta la carne. verb: gusta, because la carne is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: le because mi perro is the indirect object A mi perro le gustan los huesos. verb: gustan, because los huesos is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: le because mi perro is the indirect object A los estudiantes les gusta el profesor. verb: gusta, because el profesor is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: les because los estudiantes is the indirect object A los estudiantes no les gustan los exámenes. verb: gustan, because los exámenes is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: les because los estudiantes is the indirect object Me gusta la carne. verb: gusta, because la carne is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: me (no redundant indirect object noun phrase is required) Me gustan los mariscos. verb: gustan, because los mariscos is the subject ind. obj. pronoun: me (no redundant indirect object noun phrase is required) In addition to nouns, verbs can be the subjects of gustar, just as they can be the subject of to be pleasing. Remember that a subject answers the question, Who or What VERBs? or alternatively, Who or What is VERBing? As you look at the examples below, note how English has two ways to use a verb as a subject. To eat is pleasing to me. Eating is pleasing to me. What is pleasing? To eat / Eating. (So, to eat / eating is the subject.) To drink wine is pleasing to me. Drinking wine is pleasing to me. What is pleasing? To drink wine / drinking wine. (So, to drink wine / drinking wine is the subject.) Spanish does not have two ways to use a verb as a subject. When a verb is a subject, it appears in the -r form only (for example, hablar, comer, vivir). The previous sentences would look like the following in Spanish. Me gusta comer. Me gusta tomar vino. (comer is the subject of gusta) (tomar vino is the subject of gusta) You can never have a plural form of gustar when verbs are the subject. Me gusta comer y tomar vino. 358 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System (Even though two verbs form the subject, comer and tomar vino, the verb form is singular, gusta.) D. As we mentioned earlier, the use of a and third-person indirect object nouns (for example, John, Mary, the dog, the cats, my sisters) with gustar also requires the use of le or les, the corresponding indirect object pronouns. A Juan le gusta el perro. A los estudiantes les gusta el profesor. When the indirect object is me, you, or us, the a is used almost exclusively for emphasis and contrast, as in, Well, to me sushi isn’t pleasing. Compare the examples that follow. NORMAL ADDING EMPHASIS, CONTRAST No me gustan las zanahorias. Quizás a Juan le gustan las zanahorias pero a mí no me gustan. Te gusta ese chico. Si a ti te gusta ese chico, está bien. Pero cuidado. Nos gusta el español. A nosotros nos gusta el español, pero a ellos les gusta el francés. As you hear more and more Spanish, these subtle distinctions of emphasis and contrast will come to you. E. Self-test on gustar 1. Convert the following English sentences from like to be pleasing sentences. a. The dog likes vegetables. b. My cats like to watch television. 2. Translate the following sentences into English with be pleasing. Then convert the English sentences to like sentences. a. A Roberto le gustan los mariscos. b. A mis profesores no les gusta recibir tarea tarde. 3. Insert the correct form of gustar in each sentence. Then give an English equivalent using the verb be pleasing. a. No me los dulces. b. A mis amigos no les c. 4. ¿Te mi hermano. estudiar en la biblioteca? Insert the correct indirect object pronoun. Then give an English equivalent using the verb be pleasing. a. A Ramón no b. A los japoneses c. A mis perros gusta el yogur. gusta el pescado crudo. gustan las zanahorias crudas. Answers 1. a. The vegetables are pleasing to the dog. b. Watching (To watch) television is pleasing to my cats. 2. a. Seafood is pleasing to Robert. Robert likes seafood. b. Receiving (To receive) homework late is not pleasing to my professors. My professors don’t like receiving (to receive) homework late. 3. a. gustan; Candies are not pleasing to me. b. gusta; My brother is not pleasing to my friends. c. gusta; Is studying in the library pleasing to you? 4. a. le; Yogurt is not pleasing to Ramón. b. les; Raw fish is pleasing to the Japanese. c. les; Raw carrots are pleasing to my dogs. Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 359 VIII. Reflexive Pronouns A. So far, you’ve learned about subjects, direct objects, and indirect objects. Reflexive objects can be either direct or indirect objects. A reflexive noun or pronoun might answer the question Who or What is VERBed? or To whom or For whom is X VERBed? What is different is that reflexive nouns and pronouns refer to the same person or thing as the subject! Let’s see how this works. Let’s first identify the subjects and objects of the following sentences. The first two are done for you. By now you should be able to do the others. I see John. Who sees? I. (So, I = subject.) Who is seen? John. (So, John = direct object.) I gave a present to John. Who gives? I. (So, I = subject.) What is given? A present. (So, a present = direct object.) To whom is a present given? John. (So, John = indirect object.) John sees me. John gave me a present. Now, let’s switch the direct object in the first example. Let’s switch it so that I is both the subject and the direct object. Normally, the direct object that corresponds to I is me but in English we don’t say I see me, except in rare cases. Usually we say I see myself. Let’s apply our questions to this sentence. I see myself. Who sees? I see. (So, I = subject.) Who is seen? Me/Myself. (So, myself = direct object.) This is a classic reflexive construction and in English some form of -self or -selves is part of the reflexive pronoun. Let’s look at the second sentence, changing the indirect object so that the sentence becomes reflexive. I gave myself a present. Who gave? I. (So, I = subject.) What was given? A present. (So, a present = direct object.) To whom was a present given? To myself. (So, myself = indirect object.) Again, this is a classic reflexive construction in English. It also illustrates that the same pronoun (in this case, myself) can be either a reflexive direct object or a reflexive indirect object. So far so good. Now let’s look at the third sentence: John sees me. Let’s make John both the subject and the direct object. We wouldn’t normally say John sees John (unless there are two different Johns involved, such as Big John and Little John). We would say John sees himself. What about the fourth sentence? What if John both gives the present and receives the present? Again, we would use himself: John gives himself a present. Let’s analyze these using our questions. John sees himself. Who sees? John. (So, John = subject.) Who is seen? Him/Himself. (So, himself = direct object.) John gives himself a present. Who gives? John. (So, John = subject.) What is given? A present. (So, a present = direct object.) To whom is a present given? Him/Himself. (So, himself = indirect object.) Again, what these examples illustrate is that reflexives are merely another form of direct and indirect objects and that in English we use the same reflexive pronoun regardless of whether the object is direct or indirect. Below are some sample sentences. See if you can give the rest of the English reflexive pronouns. 360 I see myself. We see I buy it for myself. We buy it for Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System . . You see . You buy it for You ( pl.) see . You ( pl.) buy it for He sees himself. They see He buys it for himself. They buy it for . . . . She sees She buys it for It sees . . . Answers yourself, herself, itself, ourselves, yourselves, themselves Note: Some people get confused and think hisself and theirselves are pronouns, but technically they are non-standard and aren’t considered “proper” English. B. In Spanish, reflexives are also just another version of direct and indirect objects. What is different from English is that the reflexive pronouns are the same as the direct and indirect object pronouns except in the case of third-person (he, she, it, and they) and the formal Uds. The reflexive pronouns are me, te, nos, os, and se. me Veo a Juan. (I see Juan) Me veo. (I see myself.) Me compro un regalo. (I buy myself a present.) nos María y yo vemos a Juan. (María and I see Juan.) María y yo nos vemos. (María and I see each other.) María y yo nos compramos unos regalos. (María and I buy ourselves some gifts.) te Ves a Juan. (You see Juan.) Te ves. (You see yourself.) Te compras un regalo. (You buy yourself a present.) os Vosotros veis a Juan. (You all see Juan.) Vosotros os veis. (You all see yourselves.) Vosotros os comprais unos regalos. (You all buy yourselves some gifts.) se Ud. ve a Juan. (You see Juan.) Ud. se ve. (You see yourself.) Ud. se compra un regalo. (You buy yourself a present.) se Uds. ven a Juan. (You all see Juan.) Uds. se ven. (You all see yourselves.) Uds. se compran unos regalos. (You all buy yourselves some gifts.) se María ve a Juan. (María sees Juan.) María se ve. (María sees herself.) María se compra un regalo. (María buys herself a present.) se Ellos/Ellas ven a Juan. (They see John.) Ellos/Ellas se ven. (They see themselves.) Ellos/Ellas se compran unos regalos. (They buy themselves some presents.) Juan ve a María. ( Juan sees María.) Juan se ve. (Juan sees himself.) Juan se compra un regalo. ( Juan buys himself a present.) El perro ve a Juan. (The dog sees Juan.) El perro se ve. (The dog sees itself. / The dog sees himself.) Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 361 C. Some verbs that are typically reflexive in Spanish do not translate into English with some form of -self as a pronoun. These are indeed true reflexives in Spanish—it’s just that English doesn’t normally use a reflexive structure for these verbs, even though at times a person could. What is confusing is that English uses the same structure for these verbs when they are reflexive and when they aren’t. Here are the most frequent ones you will encounter. The reflexive verb for Spanish is indicated by se attached to the infinitive (unconjugated -r form). SPANISH LITERAL ENGLISH TYPICAL ENGLISH acostar Acosté al niño. acostarse to put to bed, to lay down I put the baby to bed. to put one’s self to bed, to lie one’s self down I put myself to bed late. to put to bed I put the baby to bed. to go to bed, to lie down afeitar El barbero afeitó al señor. afeitarse No me afeité esta mañana. to shave The barber shaved the man. to shave one’s self I didn’t shave myself this morning. to shave The barber shaved the man. to shave I didn’t shave this morning. bañar Bané al perro. bañarse Me bañé con Calgon. to bathe I bathed the dog. to bathe one’s self I bathed myself with Calgon. to bathe I bathed the dog. to take a bath I took a bath with Calgon. despertar Desperté a mi hijo. despertarse Me desperté temprano. to wake up I woke my son up. to wake one’s self up I woke myself up early. to wake up I woke my son up. to wake up I woke up early. ducharse* Me duché con agua fría. to shower one’s self I showered myself with cold water. to take a shower I took a shower with cold water. levantar Levanté la mesa para colocar el tapete. levantarse Me levanté del sofá. to raise, lift up I lifted up the table to put the rug in place. to raise one’s self up I raised myself from the sofa. to raise, lift up I lifted up the table to put the rug in place. to get out of bed, to get up I got up from the sofa. poner Le† puse la correa al perro. ponerse Me puse un abigo. to put I put the leash on the dog. to put on one’s self I put a coat on myself. to put on I put the leash on the dog. to put on I put on a coat. sentir Lo siento. sentirse to feel, to regret I feel/regret it. to feel something inside yourself I felt bad inside myself for what I said. to feel, to regret I’m sorry. to feel Me acosté tarde. Me sentí mal por lo que dije. I went to bed late. I felt bad for what I said. *Duchar and to shower are not normally used non-reflexively as we don’t typically shower other people but instead bathe them (yes, you can “shower someone with affection” but that’s a different meaning altogether). † When putting something on someone else, in Spanish we use indirect object pronouns and the preposition a. 362 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System SPANISH LITERAL ENGLISH TYPICAL ENGLISH vestir Vestí la muñeca de seda. vestirse Me vestí para la fiesta. to dress I dressed the doll in silk. to dress one’s self I dressed myself for the party. to dress I dressed the doll in silk. to get dressed I got dressed for the party. Self-test on Reflexives 1. Circle the sentences that when translated into Spanish would need a reflexive pronoun. a. I know him well. I know myself well. b. She loves him. c. She only loves herself. He took a bath. He bathed me. d. We put on hats. 2. We put a hat on him. e. Did you wake up early? Did you wake her up yet? f. I put him to bed. I went to bed. Now translate the sentences above from English to Spanish. Answers 1. a. I know myself well. d. We put on hats. b. She only loves herself. e. Did you wake up early? c. He took a bath. f. I went to bed. 2. a. Lo conozco bien. Me conozco bien. b. Lo quiere. Sólo se quiere a sí misma. c. Se bañó. Me bañó. d. Nos pusimos sombreros. Le pusimos un sombrero. e. ¿Te despertaste temprano? ¿La despertaste ya? f. Lo acosté. Me acosté. D. Remember what you learned about word order and correctly interpreting object pronouns and gustar? The same applies to reflexive structures. Do not interpret the reflexive pronoun as a subject pronoun. Remember that since Spanish can freely omit subjects and subject pronouns if the subject is understood, then the reflexive pronoun will appear without a subject pronoun. Don’t mistake it as a subject! Se vistió. Se vistió Juan. Me vistió Juan. Me vestí. Se is not the subject. Se is the part that refers to himself or herself. So the sentence means somebody dressed himself or herself. In more typical English, somebody got dressed. Juan is the subject and just happens to come after the verb. So, no one is dressing Juan. He’s dressing himself. Juan is still the subject as in the previous sentence and again happens to come after the verb. Who did he dress? Not himself this time but me. Me is not the subject but the pronoun that refers to myself. The verb ending tells you I is the subject so the sentence means I dressed myself or I got dressed. Self-test on Word Order and Reflexives Translate each of the following into English. a. Me bañó María. b. Se acostó el perro. Answers a. María bathed me. b. The dog went to bed. c. Lo levantamos. d. Te afeitaste. c. We lifted it. (Can also mean We woke him up.) d. You shaved (yourself). Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 363 IX. Reciprocal Reflexives A. As the term reciprocal suggests, a reciprocal action is one in which two or more entities perform the same action on each other or share the same reaction/emotion toward each other. I greet John. John and I always greet each other. Mary hates me. Mary and I hate each other. one-way and non-reciprocal action of greeting (I greet him, but he doesn’t greet me) two-way and reciprocal action of greeting (I greet John and he greets me) one-way and non-reciprocal reaction (Mary hates me, but I don’t hate her) two-way and reciprocal reaction (Mary hates me and I also hate her) The reason these are called “reflexives” is that the subjects and the objects are the same. In the second example of greeting, John and I are the subjects of the verb greet but these are also the direct objects. In the second example of hating above, Mary and I are the subjects of the verb hate but these are also the direct objects. (Remember that subjects answer the question Who or What is VERBing or VERBs?, direct objects answer the question Whom or What is VERBed? or Who or What is being VERBed? Note that the objects for reciprocal reflexives can be direct or indirect. Indirect objects answer the question To/For whom or To/For what is something VERBed? In the preceding examples, the objects are direct. In the next examples, they are indirect, but the reciprocal structure does not change. John and Mary talk to each other all the time. My sister and I send each other emails daily. two-way reciprocal, subject and indirect object the same two-way reciprocal, subject and indirect object the same As you can see, the phrase each other is a good clue to reciprocity in English. But there are common reciprocal actions that are not necessarily expressed with each other. They kissed and then hugged. They met at a party. Who hugged and kissed whom? Well, the kissers and huggers are doing these actions to each other. Who met whom? The meeters are also the people met. This is a reciprocal action. In Spanish, reciprocal reflexives look like regular reflexives. Se abrazaron. No se hablan. Nos vemos todos los días. Nos conocimos en una fiesta. They hugged (each other). They don’t talk to each other. We see each other every day. We met (each other) at a party. The equivalent of each other can be added in Spanish (although you generally won’t see it), but it is typically used for emphasis. No se hablan el uno al otro. B. By their very nature, reciprocal actions can be plural only. Think about it this way: the concept of each other implies that two or more people have to be involved, so the verb forms will always be nosotros, vosotros/Uds., or ellos/ellas. Nos abrazamos. Os abrasteis. Uds. se abrazaron. Se abrazaron Juan y María. 364 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System We hugged. You all hugged. You all (form.) hugged. Juan and María hugged. If you see or hear Me abracé, the only possible meaning is that I hugged myself (a true reflexive). The subject and object are the same, but there is no reciprocity because there are not two people doing something to each other. C. Self-test on Reciprocal Reflexives Which of the following are clearly reciprocal actions and which are not? NOT RECIPROCAL RECIPROCAL 1. Mary and Jane lied in class. F F 2. Tom and Harry shook hands when they met. F F 3. My parents exchanged looks at dinner. F F 4. My sister and I screamed. F F 5. Sue’s and Bob’s fingers touched for a moment as they passed. F F Answers 1. not reciprocal (while two people can lie to each other, there is nothing here to indicate this is the case) 2. reciprocal (the normal routine of handshaking implies two people doing it to each other, especially given the context of meeting) 3. reciprocal (the parents exchanged looks with each other) 4. not reciprocal (while two people can scream at each other, there is nothing here to indicate this is the case) 5. reciprocal (there are two sets of fingers involved: Sue’s and Bob’s, and the only interpretation possible here is that these fingers touched each other and not other people’s) X. Pseudo-Reflexives A. You will recall that the concept of reflexivity means that the subject and object of a verb are the same. In English, this is often expressed with some form of -self but not always. (If this is not clear, you may wish to review the lesson on reflexives.) John understands himself. I can see myself. I dressed and left. I showered. John is both the understander and the one understood. I am both the seer and the one being seen. I am both the dresser and the one dressed. I am both the showerer and the one who was showered. Pseudo-reflexives in a language like Spanish are called reflexives because they rely on the reflexive pronouns me, te, nos, os, and se to express an action or event. They are called pseudo- because the action is not really reflexive: the subject and object are the same but the subject is not doing the action to itself. Observe the examples below. Juan odia a María. Juan me enoja todo el tiempo. Juan se odia. Juan se enoja fácilmente. Not any kind of reflexive. Juan is the subject (the one hating) and María is the object (the person hated). Not any kind of reflexive. Juan is the subject (the one who is angering) and I am the object of the action (the one angered). True reflexive. Juan is both the hater and the one hated. Not a true reflexive. Juan gets angry; he is not doing anything to himself. He is actually experiencing something caused by external forces. This is a pseudo-reflexive. Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System 365 If a pseudo-reflexive is not a reflexive, why bother to call it reflexive at all? The answer is partly based on the fact that reflexive pronouns are involved. When linguists first tried to describe these structures that didn’t exist in their own language, their only structural point of comparison were true reflexives (“Well, it kind of looks like a reflexive. There’s a reflexive pronoun involved . . . ”) In addition, when people began to think about the situations in which these kinds of structures occurred, it is clear that no second entity was involved. That is, in something like Juan se enoja, it is impossible to add María or el mesero or el perro or another subject to the sentence to indicate what makes John mad. That sentence would have to be María (el mesero / el perro) enoja a Juan. So linguists concluded that because the event contained only one person who structurally was both the subject and the object, perhaps this constituted a special kind of reflexive. With no other name to call it, it was dubbed pseudo-reflexive. B. Most pseudo-reflexives involve some kind of emotional change, although physical change can sometimes be expressed as a pseudo-reflexive. In Spanish, typical pseudo-reflexives are to get sad, to get angry, to get embarrassed, to worry, to get irritated, among others. Nonemotional pseudo-reflexives include to get rich, to get sick, and to get well. In Spanish, the verbs used in pseudo-reflexives can also be used nonreflexively, as in these examples. NONREFLEXIVE PSEUDO-REFLEXIVE Juan irrita a su amigo. Juan irritates his friend. El niño preocupa a su mamá. The boy worries his mother. La nota enojó a Ramón. The grade made Ramón angry. La comida enfermó a Julieta. The food made Julieta sick. La medicina curó al paciente. The medicine cured the patient. El buen trabajo le hizo rica a María. Hard work made María rich. Su amigo se irrita. The friend gets irritated. La mamá se preocupa. The mother gets worried. Ramón se enojó. Ramón got angry. Julieta se enfermó. Julieta got sick. El paciente se curó. The patient got cured. María se hizo rica. María got rich. Self-test on Pseudo-Reflexives Translate each of the following sentences from Spanish to English. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Juan se enoja fácilmente. Juan enoja a María fácilmente. El perro se alegró al ver su dueño (master). El perro alegró a su dueño cuando le dio un beso. El precio me preocupa. Me preocupo por todo. ¿Qué malos hábitos te irritan? ¿Te irritas fácilmente? Answers 1. Juan gets angry easily. 2. Juan angers María /makes María angry easily. 3. The dog got happy when it saw its master. 4. The dog made his master happy when he gave him a kiss. 5. The price worries me. 6. I get worried about everything. 7. What bad habits annoy/irritate you? 8. Do you get annoyed/irritated easily? 366 Appendix 1: The Spanish Pronoun System