El problemático lugar de José Rizal dentro de la literatura española

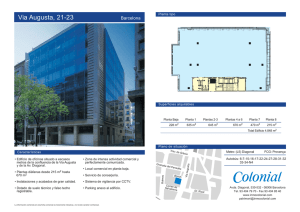

Anuncio