Alejandro Carballo Leyda - Revista Electrónica de Estudios

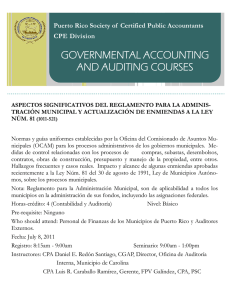

Anuncio