Inside Outside In-Between

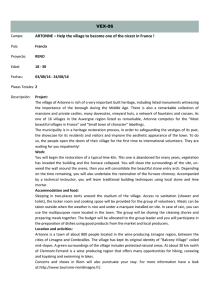

Anuncio