Energy consumption in the management of avocado orchards in

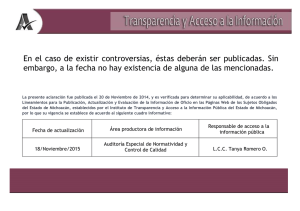

Anuncio