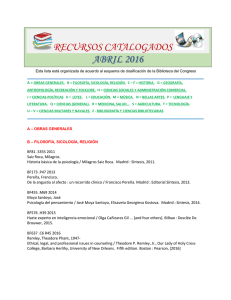

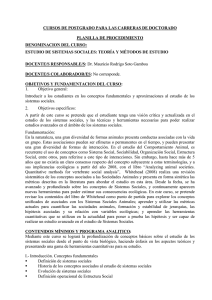

Bibliografía sobre revoluciones: teorías e investigaciones

Anuncio