33AmIndLRev201(2009)HatueyChe - Larry Catá Backer`s Personal

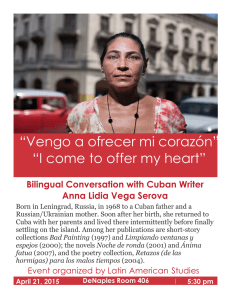

Anuncio