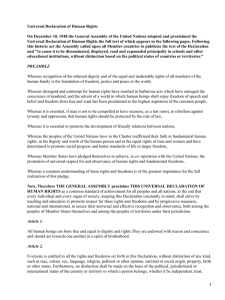

human dignity according to international instruments on human

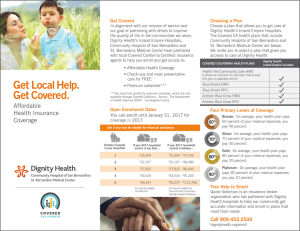

Anuncio