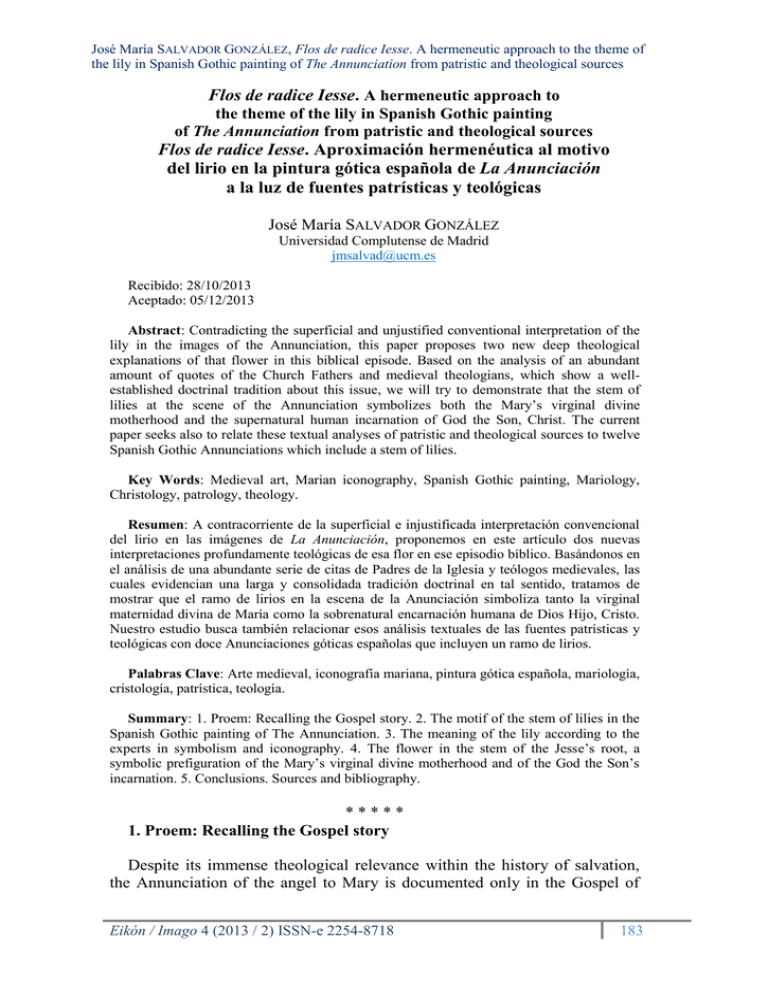

Flos de radice Iesse. Aproximación hermenéutica al motivo

Anuncio