antonio saura - Accion Cultural Española

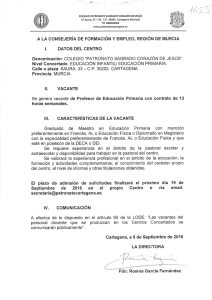

Anuncio