Thailand in 2016: restoring democracy or reversing it?

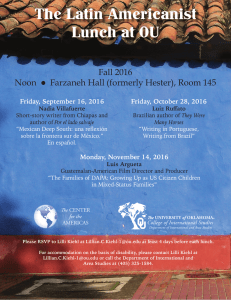

Anuncio