Percepción e imagen de los consumidores españoles del pescado

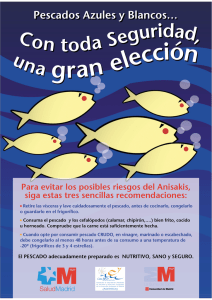

Anuncio