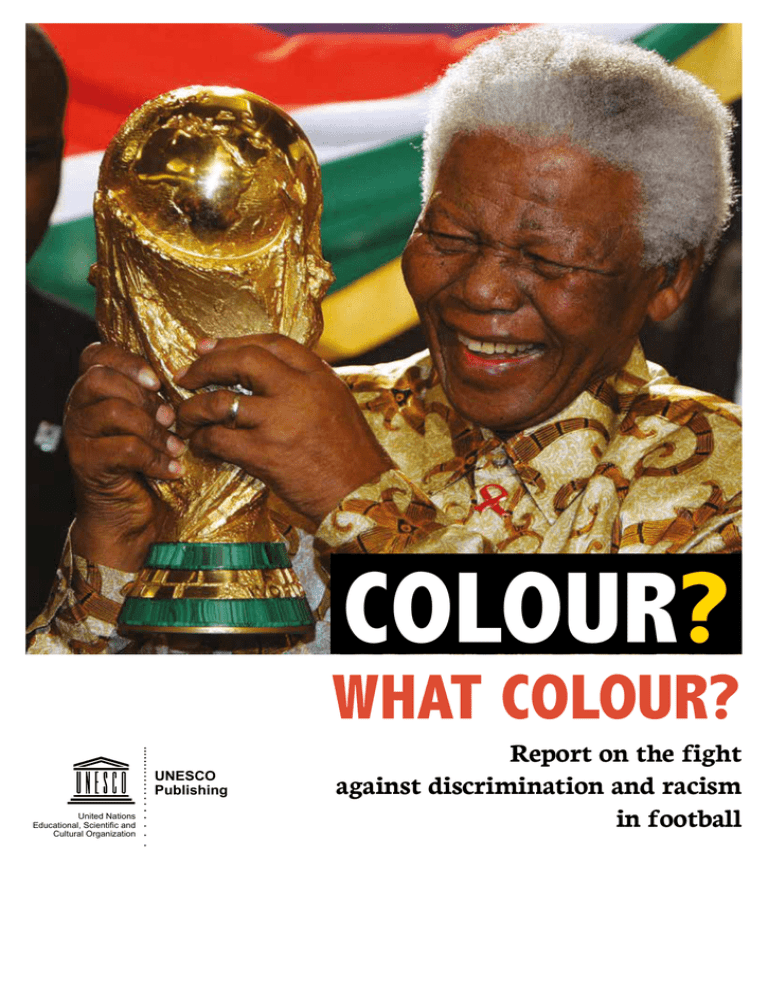

what colour?

Anuncio