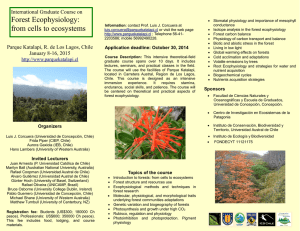

Bío Bío Region, Chile

Anuncio