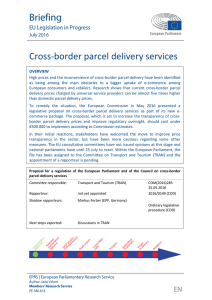

E-commerce and delivery

Anuncio