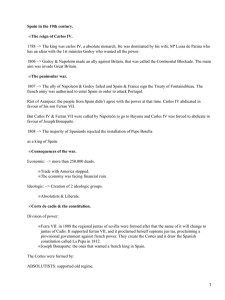

From Founding Father to Pious Son

Anuncio