Inter-American Court of Human Rights

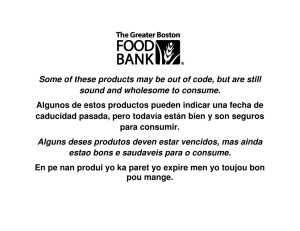

Anuncio