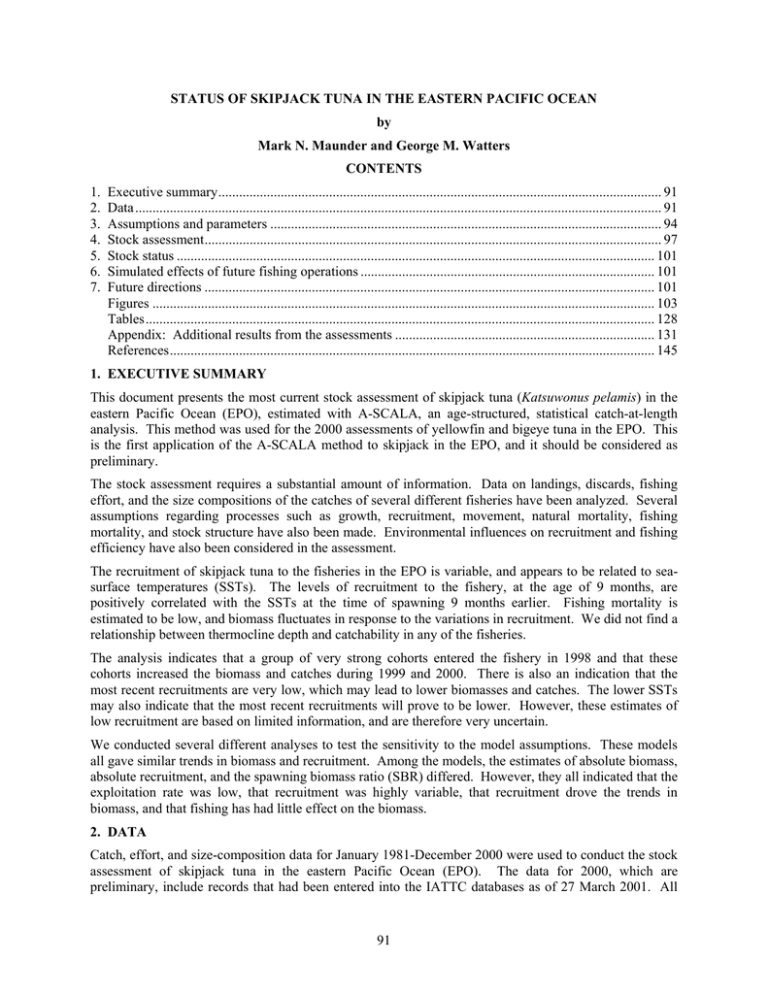

91 STATUS OF SKIPJACK TUNA IN THE EASTERN PACIFIC

Anuncio