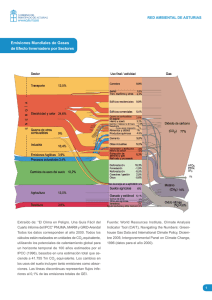

Primer on Short-Lived Climate Pollutants

Anuncio