03-024 (Transformación genética...)

Anuncio

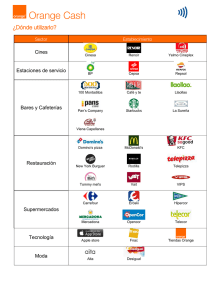

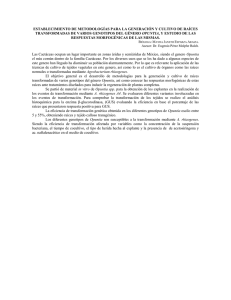

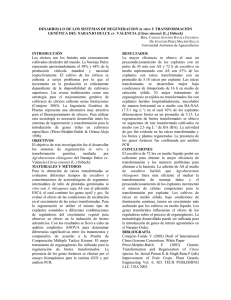

TRANSFORMACIÓN GENÉTICA DEL NARANJO AGRIO USANDO Agrobacterium rhizogenes GENETIC TRANSFORMATION OF SOUR ORANGE USING Agrobacterium rhizogenes Norma A. Chávez-Vela, Lucía I. Chávez-Ortiz, y Eugenio Pérez-Molphe Balch Centro de Ciencias Básicas. Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes. Av. Universidad 940. 20100 Aguascalientes, Aguascalientes, México. Tel.: (449)910-84-20, Fax. (449)910-84-01 ([email protected]) RESUMEN ABSTRACT Se regeneraron plantas transgénicas de naranjo agrio (Citrus aurantium L.) a partir de raíces transformadas con Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Para obtener las raíces transformadas se cocultivaron, por 96 h, segmentos internodales de tallo de plántulas germinadas in vitro con A. rhizogenes cepa A4 con el plásmido ESC4 que contiene los genes nptII y gus. La mayor eficiencia se obtuvo al usar una suspensión de 1× ×108 células −1 mL y 96 h de cocultivo. En estas condiciones, 91% de los explantes produjeron raíces transformadas, con un promedio de 3.6 raíces por explante. Para la regeneración de brotes se cultivaron segmentos de raíz transformada en medio con 5.0 mg L−1 de benciladenina (BA) y 1.0 mg L−1 de ácido naftalenacético (ANA). En este medio, 18% de los segmentos de raíz transformada produjeron brotes adventicios con un promedio de 1.25 brotes por explante. La actividad de gus fue evidente en las raíces transformadas y los brotes y plantas regeneradas. La presencia de los genes foráneos fue confirmada por análisis PCR y Southern blot. Este sistema se utilizó posteriormente para generar raíces y brotes de naranjo agrio transformados con el gen que codifica para la proteína de la cápside del Virus de la Tristeza de los Cítricos. Transgenic Sour orange (Citrus aurantium L.) plants were regenerated from Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed roots. To obtain the transformed roots, internodal stem segments from in vitro germinated seedlings were cocultured for 96 h with Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain A4 with the ESC4 plasmid that contains the nptII and gus genes. The highest efficiency was obtained using a suspension of 1× ×108 cells mL−1 and 96 h of coculture. Under these conditions, 91% of the explants produced transformed roots with an average of 3.6 roots per explant. For shoot regeneration, segments of transformed roots were cultured on regeneration medium with 5.0 mg L−1 benzyladenine (BA) and 1.0 mg L−1 napthaleneacetic acid (NAA). In this medium, 18% of the transformed root segments produced adventitious shoots, with an average of 1.25 shoots per explant. Gus activity was evident in the transformed roots, shoots and regenerated plants. The presence of the foreign genes was confirmed by PCR analysis and Southern blot. Afterwards, this system was used to generate sour orange roots and shoots transformed with the gene that codes for the capsid protein of the Citrus Tristeza Closterovirus. Keywords: Citrus aurantium, citrus Tristeza Closterovirus (CTV), Palabras clave: Citrus aurantium, raíces transformadas, virus de la Tristeza de los Cítricos (VTC). transformed roots. INTRODUCTION INTRODUCCIÓN S our orange (Citrus aurantium L.) is used for extraction of essential oils and production of marmalades and conserved foods. However, its greatest importance lies in its use as rootstock for production of other Citrus species. In México, practically all commercial plantations of sweet orange, tangerine and grapefruit, as well as 16% of Mexican lime, are grafted on sour orange, which represents 85% to 90% of Mexican citrus production. Such a widespread use of sour orange is due to the fact that it supports crops of excellent internal quality, with high content of soluble solids and acidity, apart from its greater tolerance to drought and alkaline soils in comparison to other E l naranjo agrio (Citrus aurantium L.) se utiliza para la extracción de aceites esenciales y para la elaboración de mermeladas y conservas. Sin embargo, su mayor importancia radica en su uso como portainjertos para la producción de otros cítricos. En México, prácticamente todas las plantaciones comerciales de naranja dulce, mandarina y toronja, así como 16% de limón mexicano, están injertados sobre naranjo agrio, lo que representa 85 a 90% de la citricultura nacional. Esto se debe a que promueve cosechas de excelente Recibido: Abril, 2003. Aprobado: Octubre, 2003. Publicado como ARTÍCULO en Agrociencia 37: 629-639. 2003. 629 630 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 37, NÚMERO 6, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2003 calidad interna, con altos contenidos de sólidos solubles y acidez, y es más tolerante a la sequía y a suelos alcalinos que otros portainjertos. Es resistente a la gomosis, exocortis, xiloporosis y psorosis de los cítricos, aunque altamente susceptible al Virus de la Tristeza de los Cítricos (VTC) (Orozco-Santos, 1996; DurónNoriega et al., 1999), lo que ha impulsado la substitución del naranjo agrio por otros patrones que no tienen todas sus ventajas pero son más tolerantes al VTC (Rocha-Peña et al., 1995). La única opción para seguir usando el naranjo agrio como portainjertos es la generación de plantas resistentes a VTC, y la herramienta más eficiente para lograrlo es la transformación genéticas. En la mayoría de transformaciones genéticas en cítricos se ha usado sistemas basados en Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Peña y Navarro, 1999). Con la transformación genética del naranjo agrio mediante el uso de A. tumefaciens se obtuvieron dos plantas transgénicas con los genes gus, nptII y el de la cápside del VTC (Gutiérrez et al., 1997). El estudio de factores que afectan la transformación de esta especie por A. tumefaciens permitió desarrollar un sistema más eficiente para generar algunas plantas transformadas con el gen de la cápside del VTC (Ghorbel et al., 2000). Los sistemas para la transformación genética de cítricos mediada por A. tumefaciens tienen algunas desventajas: La baja eficiencia y alto porcentaje de quimeras; la baja tasa de enraizamiento de los brotes transgénicos, lo que obliga en muchos casos a microinjertarlos sobre patrones no transformados con el fin de recuperar plantas completas (Peña et al. 1995, 1999; Cervera et al. 1998a y b). Por tanto, este sistema de transformación es poco aplicable a especies utilizadas como patrones y con un sistema radical propio, como el naranjo agrio. Un método que podría evitar estas desventajas sería usar Agrobacterium rhizogenes como vector para la transformación, y consiste en la generación de raíces transformadas con los genes silvestres del plásmido Ri, más los genes de interés en cada caso. Luego las raíces transformadas serían usadas como explantes para la regeneración de brotes transgénicos por la vía de la organogénesis. La obtención de plantas transgénicas por este método se ha reportado sólo para siete especies de frutales (Christey, 2001). En limón mexicano (Citrus aurantifolia Christm.), la transformación con A. rhizogenes ha sido más eficiente que la basada en A. tumefaciens. Además, no se producen quimeras y los brotes transgénicos generados forman raíces con facilidad, probablemente debido a la inserción en el genoma de la planta de los genes rol de A. rhizogenes (Pérez-Molphe-Balch y Ochoa-Alejo, 1998). A pesar de estas ventajas, la transformación genética del naranjo agrio usando A. rhizogenes no se ha reportado. En este trabajo se describe el desarrollo de un sistema de transformación para el naranjo agrio basado en el uso de rootstocks. It is resistant to citrus gummosis, exocortis, xyloporosis and psorosis, but highly susceptible to Citrus Tristeza Closterovirus (CTV) (Orozco-Santos, 1996; Durón-Noriega et al., 1999). The above mentioned has supported a strong trend of substitution of sour orange for other rootstocks, that lack some of its advantages, but are more tolerant to CTV (Rocha-Peña et al., 1995). The only alternative that would allow for continual use of sour orange as a rootstock in presence of CTV is the generation of CTV-resistant plants. The most efficient tool to attain this goal is genetic transformation. In most of genetic transformation of Citrus species Agrobacterium tumefaciens-based transformation systems have been used (Peña and Navarro, 1999). Gutiérrez et al. (1997) reported genetic transformation of sour orange using A. tumefaciens, and obtained two transgenic plants with gus, nptII and CTV capsid genes. Ghorbel et al. (2000) studied several factors that affect transformation of this species by A. tumefaciens, and developed a more efficient system to generate some plants transformed with the CTV capsid gene. A. tumefaciens-mediated genetic transformation systems for Citrus species have exhibited certain disadvantages: low efficiency and high proportion of chimeras; low rooting ratio of transgenic shoots, which in many cases has forced researchers to perform micro-grafts on untransformed rootstocks in order to retrieve whole plants (Peña et al. 1995, 1999, Cervera et al. 1998a y b). As a result, this transformation system has low application to species used as rootstocks and with a root system of their own, such as sour orange. A method that could eliminate these disadvantages would be the use of Agrobacterium rhizogenes as a transformation vector. This system consists of transformed root generation with the wild-type plasmid Ri genes, plus the genes of interest in each case. Then, transformed roots would be used as explants for regeneration of transgenic shoots via the organogenesis path. Obtainment of transgenic plants by this method has been reported for only seven species of fruit crops (Christey, 2001). Transformation with A. rhizogenes in Mexican lemon (Citrus aurantifolia Christm.) has proved to be more efficient than A. tumefaciens-based transformation. Furthermore, chimeras are not produced and transgenic shoots grow roots with ease, probably owed to the insertion of A. rhizogenes rol genes in the plant genome (Pérez-Molphe-Balch y Ochoa-Alejo, 1998). Despite these advantages, genetic transformation of sour orange using A. rhizogenes has not been reported. The development of an A. rhizogenes-based transformation system for sour orange is described in this work, as well as its use for insertion of the gene that codes for the CTV capsid protein into the sour orange genome. CHÁVEZ-VELA et al.: TRANSFORMACIÓN GENÉTICA DEL NARANJO AGRIO USANDO Agrobacterium rhizogenes A. rhizogenes, así como su utilización para la introducción en su genoma de un gen que codifica para la proteína de la cápside del VTC. MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS 631 MATERIALS AND METHODS Plant material Seventy-five-day-old sour orange seedlings were used as source of explants for generation of transformed roots. The Material vegetal seedlings were obtained from seeds germinated in aseptic conditions. Seeds were collected from selected ripe fruit produced Como fuente de explantes para la generación de raíces transformadas se utilizaron plántulas de naranjo agrio (75 d edad), obtenidas a partir de semillas germinadas en condiciones asépticas. Las semillas se recolectaron de frutos maduros seleccionados procedentes del banco de germoplasma del Campo Experimental Tecomán (Colima) del Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP). Las semillas se desinfectaron lavándolas tres veces por 10 min con detergente líquido (Dermoclean) a 1% y enjuagándolas con agua corriente; luego se lavaron con etanol a 70% durante 45 s y se trataron por 25 min con una solución de blanqueador comercial (Cloralex) a 15%. Finalmente se enjuagaron cuatro veces con agua destilada estéril bajo condiciones de asepsia y se inocularon en el medio de cultivo. El medio utilizado fue MS 50% (Murashige y Skoog, 1962), pH 5.7 y con 8 g L−1 de agar (Sigma). Los cultivos se mantuvieron en la oscuridad a 25±2 oC por dos meses aproximadamente, y luego se incubaron dos semanas bajo luz continua (54 mmol m−2 s−1). in the Germoplasm Bank of the Tecomán Experimental Field of the INIFAP (Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias). The seeds were disinfected by washing them three times during 10 min with 1% Dermocleen, and rinsed with tap water; then they were washed with 70% percent ethanol during 45 s and treated 25 min with a 15% commercial bleach (Cloralex) solution. Finally, seeds were rinsed four times with sterile distilled water in aseptic conditions and inoculated in culture medium. The medium utilized was 50% MS (Murashige & Skoog, 1962), pH 5.7 with 8 g L−1 agar (Sigma). Cultures were kept in the dark at 25±2 o C during two months approximately, then incubated two weeks under continuous light (54 mmol m−2 s−1). Induction of transformed roots A. rhizogenes A4 agropine-type strain was used to develop the transformation system. A4 contains wild-type plasmid pRi A4 which confers hairy-root genotype, and binary vector pESC4. Inducción de raíces transformadas Para el desarrollo del sistema de transformación se utilizó la Cepa A4 de A. rhizogenes, del tipo agropina, y contiene el plásmido silvestre pRi A4 que confiere el genotipo de raíces pilosas, y el plásmido pESC4 como vector binario. Este último lleva el gen marcador de selección nptII bajo el control del promotor y terminador nos, y el gen reportero de gus bajo el control del promotor cab y el terminador ocs (Jofre-Garfias et al., 1997). Una vez conocidas las condiciones óptimas para la transformación, se utilizó también el plásmido binario B249CP-pGA482GG, el cual, además de los genes nptII y gus, contiene el gen que codifica para la cápside de una variante severa del VTC originaria de Venezuela (B249). Este gen se encuentra bajo el control de un promotor constitutivo 35S. Para el cocultivo, la bacteria se inoculó en medio YMB líquido (Hooykaas et al., 1977) con 50 mg L−1 de rifampicina y 50 mg L−1 de kanamicina para el pESC4, o bien 50 mg L−1 de rifampicina y 12 mg L−1 de tetraciclina para el B249CP-pGA482GG, y se incubó 72 h a 28 oC con agitación orbital a 120 rpm. La densidad de la bacteria se determinó a partir de la medición de absorbancia a 620 nm e interpolando en una curva patrón. El cultivo bacteriano se diluyó en medio MS líquido. El cocultivo se realizó colocando segmentos internodales de 20 mm, con cortes transversales, dentro de la suspensión bacteriana, por 45 min. Luego se eliminó el exceso de bacteria con una gasa estéril y los explantes se transfirieron a medio MS sólido sin antibióticos ni reguladores del crecimiento. Los cultivos se mantuvieron en la obscuridad a 28 oC por 48 a 96 h; The latter carries the selection marker nptII gene under control of nos promoter and terminator, and reporter gene gus under control of cab promoter and ocs terminator (Jofre-Garfias et al., 1997). Once optimal conditions for transformation were known, the binary plasmid B249CP-pGA482GG was used as well, which in addition to nptII and gus genes contains the gene that codes for the capsid protein of a Venezuelan severe variant of CTV (B249). This gene is under control of a 35S constitutive promoter. For co-culture, bacteria were inoculated in liquid YMB medium (Hooykaas et al., 1977) with 50 mg L−1 rifampicin and 50 mg L−1 kanamycin for pESC4, or 50 mg L−1 rifampicin and 12 mg L−1 tetracyclin for B249CP-pGA482GG, and were incubated 72 h at 28 oC on orbital stirrer at 120 rpm. Bacterial density was determined from absorbance measurement at 620 nm and interpolation on a reference curve. Bacterial culture was diluted in liquid MS medium. Co-culture was carried out by placing 20 mm internodal segments, with transverse cuts, in the bacterial suspension for 45 min. Excess bacteria were eliminated with sterile gauze and explants were transferred to solid MS medium without antibiotics or growth regulators. Cultures were kept in the dark at 28 oC for 48-96 h, then the explants were transferred to selection medium. The variables tested to establish the best conditions for co-culture were bacterial suspension concentration (1×107, 1×108 and 1×109 cells mL−1) and time of co-culture (48, 72 and 96 h), performing nine treatments in a completely random experimental design. Thirty explants per treatment were used and three repetitions of the experiment were conducted. 632 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 37, NÚMERO 6, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2003 después los explantes se transfirieron a medio de selección. Las variables para establecer las mejores condiciones para el cocultivo fueron la concentración de la suspensión bacteriana (1×107, 1×108 y 1×109 células mL−1) y el tiempo de cocultivo (48, 72 y 96 h), con nueve tratamientos en un diseño completamente al azar. Se utilizaron 30 explantes por tratamiento y se hicieron tres repeticiones del experimento. Posteriormente se probó el efecto de la adición de acetosiringona en la suspensión bacteriana en concentraciones de 0, 50, 100 y 200 µM. El diseño fue completamente al azar con 30 explantes por tratamiento y tres repeticiones. Se utilizó la concentración bacteriana y tiempo de cocultivo consideradas mejores del primer experimento (1×108 células mL−1 y 96 h). El medio de selección fue el MS con 5% de sacarosa, 0.8% de agar, 500 mg L−1 de cefotaxima (Claforan, Russell), 500 mg L−1 de carbenicilina (Carbecin, Sanfer), para eliminar a la bacteria, y 50 mg L−1 de kanamicina (Sigma-Aldrich) como agente selectivo. Los cultivos se incubaron a 28 oC en la oscuridad. Los resultados se registraron a los 30 d y las respuestas evaluadas fueron el porcentaje de explantes que presentaron raíces y el número de raíces por explante. Para conocer el efecto de los tratamientos, se usó un análisis de varianza y una prueba de comparación de medias de Tukey. Las raíces obtenidas en los experimentos anteriores se subcultivaron cada 30 d a medio de selección fresco y se incubaron en dos condiciones de iluminación: Luz continua (54 mmol m−2 s−1) y obscuridad, para determinar cuál de las dos condiciones favorecía el crecimiento de las raíces transformadas. Para lo anterior se registró el crecimiento de las raíces al final del ciclo de cultivo y los datos se analizaron mediante una prueba de Mann-Whitney. Regeneración de brotes adventicios a partir de las raíces transformadas Se transfirieron segmentos de raíces transformadas a medios de selección adicionados con tres combinaciones de reguladores del crecimiento: a) 2.5 mg L−1 de BA con 0.5 mg L−1 de ANA; b) 5.0 mg L−1 de BA con 1.0 mg L−1 de ANA; c) 10 mg L−1 de BA con 2.0 mg L−1 de ANA. Estos tratamientos se seleccionaron con base en experimentos previos con tejido no transformado (no se muestran esos datos). Como explantes se probaron segmentos de raíz transformada de 15 mm de longitud inoculados en posición horizontal con cortes transversales a lo largo del segmento, e inoculados en posición vertical con la parte proximal sobresaliendo del medio. Los cultivos se incubaron en la oscuridad durante 8 d y luego bajo luz continua (54 mmol m−2 s−1) a 25 ± 2 oC. Para este experimento se utilizó un diseño completamente al azar con 30 explantes por tratamiento y dos repeticiones. Después de 30 d se registró el porcentaje de explantes que presentaron brotes y el número de brotes por explante. Se usó un análisis de varianza y una prueba de comparación de medias de Tukey. Los brotes mayores de 15 mm se separaron del explante original y se transfirieron a medio sin reguladores para su enraizamiento. Las plantas generadas se pasaron a suelo, conservándose por 40 d en una cámara bioclimática y luego en invernadero. Afterwards, the effect of adding acetosyringone to bacterial suspension was tested, for 0, 50, 100 and 200 µM concentrations. A completely random design was also used, with 30 explants per treatment and three repetitions. In this case were used the bacterial concentration and co-culture time that proved best in the first experiment (1×108 cells mL−1 and 96 h). MS was used as selection medium, with 5% sucrose, 0.8% agar, 500 mg L−1 cefotaxime (Claforan, Russell), 500 mg L−1 carbenicilin (Carbecin, Sanfer), both used to eliminate bacteria, and 50 mg L−1 kanamycin (SigmaAldrich) as selection agent. Cultures were incubated at 28 oC in the dark. Results were recorded after 30 d and the evaluated responses were percentage of root-bearing explants and number of roots per explant. To know the effect of the treatments, recorded data were put through an analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a Tukey Multiple Comparison test was used. The roots obtained in these experiments were sub-cultured every 30 d in fresh selection medium, and were incubated under two illumination conditions: continuous light (54 mmol m−2 s−1) and darkness. The reason for this was to determine which conditions favored growth of transformed roots. In this manner, root growth was recorded at the end of the culture cycle and data were analyzed in a MannWhitney test. Regeneration of adventitious shoots from transformed roots Transformed root segments were transferred to selection medium containing three combinations of growth regulators: a) 2.5 mg L−1 BA with 0.5 mg L−1 ANA; b) 5.0 mg L−1 BA with 1.0 mg L−1 ANA; c) 10 mg L−1 BA with 2.0 mg L−1 ANA. These treatments were selected based on previous experiments with untransformed tissue (data not shown). Transformed root segments (15 mm) were tested as explants, inoculated horizontally with transverse cuts throughout the segments, and inoculated in upright position with the near end jutting out of the medium. Cultures were incubated in the dark for 8 d, then kept under continuous light (54 mmol m−2 s−1) at 25±2 oC. A completely random design was used in this experiment, with 30 explants per treatment and two repetitions. Percentage of shoot-bearing explants as well as number of shoots per explant were recorded after 30 d. An analysis of variance and a Tukey Multiple Comparison test were used. Shoots longer than 15 mm were separated from the original explant and transferred to medium without regulators in order to produce roots. The obtained plants were transferred to soil, and kept for 40 days in a bioclimatic chamber and later in a greenhouse. Characterization of transformed tissues The histochemical assay to detect gus activity was carried out by incubation of segments of presumptively transformed roots, shoots and leaves, as well as negative controls, with the following reagent mix: 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, 10 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 0.5 mM potassium ferricyanide, CHÁVEZ-VELA et al.: TRANSFORMACIÓN GENÉTICA DEL NARANJO AGRIO USANDO Agrobacterium rhizogenes Caracterización de los tejidos transformados. El ensayo histoquímico para detectar la actividad de gus se hizo incubando segmentos de raíz, brotes y segmentos de hojas presuntamente transformados, así como testigos negativos, con una mezcla de reacción (amortiguador de fosfatos 0.1 M, pH 7.0, EDTA 10 mM, ferrocianuro de potasio 0.5 mM, ferricianuro de potasio 0.5 mM, Tritón X-100 0.1% v/v y 5-bromo-4-cloro-3indolil-β-D-glucuronido 1 mM) a 37 oC hasta observar el precipitado color magenta en los tejidos transformados. Se eliminó la clorofila de los tejidos lavándolos con etanol a 96%. Para el análisis PCR se extrajo el ADN de los tejidos vegetales (Edwards et al, 1991). Los genes a amplificar en el ADN vegetal transformado con pESC4 fueron gus, nptII, rolB y virD1 (Hamill et al., 1991). El gen virD1 de Agrobacterium no se transfiere al genoma de la planta, por lo que se utiliza para descartar la presencia residual de la bacteria en el tejido vegetal. Para el gen gus el iniciador 5’ fue GGTGGGAAAGCGCGTTACAAG, y el 3’ GTTTACGCGTT GCTTCCGCCA; éstos amplifican un segmento de 1200 pb. Para el gen nptII el iniciador 5´ fue TATTCGGCTATGACTGGGCA, y el 3´ GCCAACGCTATGTCCTGAT; éstos amplifican un segmento de 517 pb. Para rolB el iniciador 5’ fue ATGGATCCCAAA TTGCTATTCCTTCCACGA, y el 3’ TTAGGCTTCTTTCTT CAGGTTTACTGCAGC; éstos amplifican un segmento de 780 pb. Para virD1 el iniciador 5’ fue ATGTCGCAAGGA CGTAAGCCCA, y el 3’, GGAGTCTTTCAGCATGGAGCAA; éstos amplifican un segmento de 450 pb. En las raíces y brotes transformados con el plásmido B249CP-pGA482GG, se amplificó un segmento de 720 pb del gen de la cápside del VTC. El iniciador 5’ fue GGTTTGAACCATGGACGACGAAACAAA GAAATTG, y el 3’, GGAACTCCACCA TGGCGATAGAAACC GGGAATCGG. Los productos de la amplificación se analizaron en un gel de agarosa a 1.25% teñido con bromuro de etidio. Para el Southern blot se extrajo ADN de raíces presuntamente transformadas [Draper y Scott, 1988]. El ADN fue digerido con HindIII y separado en un gel de agarosa a 0.7%; se utilizaron 20 mg de ADN por carril. Después de la electroforesis el gel se desnaturalizó con NaOH 0.5 M y NaCl 1.5 M, luego se neutralizó con Tris-HCl pH 8.0 1 M y NaCl 1.5 M, se transfirió por capilaridad a una membrana de nylon (Amersham Hybond-N+) y se fijó a 90 oC por 2 h. La sonda fue un fragmento de 517 pb del gen npt II marcado con digoxigenina (DIG). El marcaje de la sonda, la hibridización y la detección se realizaron con el “Dig High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II” (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN Inducción de raíces transformadas Se obtuvieron raíces transformadas en todas las combinaciones de concentración bacteriana y tiempo de cocultivo (Figura 1a). Sin embargo, la frecuencia de los explantes que responden formando raíces, y el número promedio de raíces por explante, fueron mayores al cocultivar por 96 h con una suspensión de 1×108 células mL−1 (Cuadro 1). 633 1% v/v Triton X-100 and 1 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-βD-glucuronid. The reaction was conducted at 37°C until a magenta precipitate showed up in transformed tissues. Chlorophyll was eliminated from tissues by washing them with 96% ethanol. Plant DNA for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was extracted using the method by Edwards et al. (1991). The genes to be amplified in pESC4-transformed plant DNA were gus, nptII, rolB and virD1, (Hamill et al., 1991). Agrobacterium virD1 gene is not transferred to plant genome; therefore, it is used to discard residual presence of bacteria in plant tissue. For the gus gene the 5’ primer was GGTGGGAAAGCGCGTTACAAG, and 3’ GTTTACGCGTTGC TTCCGCCA. These two amplify a 1200 bp segment. For the nptII gene the 5’ primer was TATTCGGCTATGACTGGGCA, and 3’ GCCAACGCTATGTCCT GAT, and they amplify a 517 bp segment. For the rolB gene the 5’ primer was ATGGATCCCAAATTGCTATTCCTTCCACGA, and 3’ TTAGGCTTCTTTCTTCAGGTTTACTGCAGC, and these two amplify a 780 bp segment. For virD1 the 5’ primer was ATGTCGCAAGGACGTAAGCCCA, and 3’, GGAGTCTTTCAGC ATGGAGCAA. These two amplify a 450 bp segment. In shoots and roots transformed with the B249CP-pGA482GG plasmid, a 720 bp segment of the CTV capsid gene was amplified. The 5’ primer was GGTTTGAACCATGGACGACGAAACAAAGAA ATTG, and 3’, GGAACTCCACCATGGCGATAGAAACCGGGA ATCGG. Amplification products were analyzed in a 1.25% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. DNA for Southern blot was extracted from putatively transformed roots (Draper and Scott, 1988). DNA was digested with HindIII and separated in a 0.7% agarose gel; 20 mg of DNA were used per lane. After electrophoresis the gel was denatured with 0.5 M NaOH and 1.5 M NaCl, then neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 1.5 M NaCl, then blotted to a nylon membrane (Amersham Hybond-N+) and fixed at 90 oC for 2 h. The probe was a 517 bp fragment of the npt II gene labeled with digoxigenin (DIG). Labeling, hybridization and detection of the probe were carried out with the “Dig High Prime DNA Labeling and Detection Starter Kit II” (Boehringer Mannheim, Germany). RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Induction of transformed roots Transformed roots were obtained in all combinations of bacterial concentration and co-culture time tested (Figure 1a). However, the frequency of root formation in explants, as well as the mean number of roots per explant, were higher for the 96 h co-culture with a 1×108 cells mL−1 suspension (Table 1). Root generation frequency is similar to the one observed in Mexican lime, where 94% of the explants co-cultured with the same A. rhizogenes strain generated transformed roots (Pérez-Molphe-Balch and Ochoa-Alejo, 1998). Addition of acetosyringone caused a higher frequency of root-bearing explants when 50 µM of this 634 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 37, NÚMERO 6, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2003 a d f c b e g Figura 1. a) Generación de raíces transformadas en segmentos de tallo de naranjo agrio. b) Ensayo histoquímico para la detección de gus en segmentos de raíces transformadas de naranjo agrio. La de la izquierda es un testigo no transformado (barra = 1 mm). c) Generación de brotes en el extremo de un segmento de raíz transformada de naranjo agrio cultivada en un medio con 5 mg L−1 BA y 1.0 mg L−1 ANA (barra = 1 mm). d) Ensayo histoquímico para gus en el extremo de un segmento de raíz transformada de naranjo agrio con un primordio de brote. Nótese la actividad de gus en el brote en formación (barra = 1 mm). e) Planta transgénica de naranjo agrio regenerada a partir de raíces transformadas con el plásmido ESC4. f) Generación de raíces transformadas en segmentos de tallo de naranjo agrio cocultivados con A. rhizogenes A4/B249CP-pGA482GG. g) Generación de brotes en el extremo de un segmento de raíz de naranjo agrio transformada con el plásmido B249CP-pGA482GG (barra = 1 mm). Figura 1. a) Generation of transformed roots in sour orange stem segments. b) Histochemical assay for detection of GUS sour orange transformed root segments. Left: untransformed control (bar = 1 mm). c) Generation of shoots on one end of a sour orange transformed root segment cultured in medium with 5 mg L−1 BA and 1.0 mg L−1 ANA (bar = 1 mm). d) Histochemical assay for detection of gus on one end of a sour orange transformed root segment with shoot primordium. Notice gus activity on emerging shoot (bar = 1 mm). e) Sour orange transgenic plant regenerated from roots transformed with ESC4 plasmid. f) Generation of transformed root from sour orange stem segments co-cultured with A. rhizogenes A4/ B249CP-pGA482GG. g) Generation of shoots on one end of a sour orange root transformed with plasmid B249CPpGA482GG (bar = 1 mm). CHÁVEZ-VELA et al.: TRANSFORMACIÓN GENÉTICA DEL NARANJO AGRIO USANDO Agrobacterium rhizogenes La frecuencia de generación de raíces es similar a la observada en limón mexicano, donde 94% de los explantes cocultivados con la misma cepa de A. rhizogenes generaron raíces transformadas (PérezMolphe-Balch y Ochoa-Alejo, 1998). La adición de acetosiringona causó una mayor frecuencia de explantes con raíces al añadir 50 µM de este compuesto a la suspensión bacteriana, aunque 200 µM mostró un efecto inhibitorio (Cuadro 2). Este mismo fenómeno se ha reportado en otras especies al ser transformadas con A. rhizogenes. En Brassica oleracea var. italica, la frecuencia de explantes con raíces transformadas se incrementa al usar 50 µM de acetosiringona, pero al elevar la concentración a 100 µM este valor baja (Henzi et al., 2000). En el número de raíces por explante no hubo diferencias significativas entre las cuatro concentraciones de acetosiringona (Cuadro 2). Las raíces transformadas mantenidas en la obscuridad mostraron un mayor crecimiento (6.7±1.5 cm en 30 d), respecto a las incubadas en luz continua, que sólo incrementaron 0.7±0.15 cm en el mismo período, diferencia significativa según la prueba de Mann-Whitney. Las raíces incubadas bajo luz continua mostraron un menor crecimiento, pero se mantuvieron vigorosas y adquirieron un color verde debido a la síntesis de clorofilas. Regeneración de brotes adventicios a partir de las raíces transformadas Los segmentos de raíces transformadas inoculados en posición vertical formaron brotes adventicios en el extremo superior 15 a 30 d después de su transferencia a dos de los tres medios de regeneración probados (Cuadro 3) (Figura 1c). La mayor frecuencia de explantes que generaron brotes se observó en el medio con 5.0 mg L−1 de BA y 1.0 mg L−1 de ANA. El número promedio de brotes por explante no mostró diferencia significativa entre los dos tratamientos que produjeron brotes. En el tratamiento con 10.0 mg L−1 de BA y 2.0 mg L−1 de ANA no se observó respuesta alguna, debido probablemente a que estas concentraciones elevadas de reguladores del crecimiento resultaron tóxicas para el tejido. La eficiencia de la combinación de BA con ANA para la generación de brotes transformados en naranjo agrio ha sido reportada por Ghorbel et al. (2000), quienes trabajaron con un sistema de transformación basado en A. tumefaciens. La eficiencia de generación de brotes a partir de segmentos de raíz transformada obtenida en naranjo agrio es inferior a la observada en limón mexicano (PérezMolphe-Balch y Ochoa-Alejo, 1998), donde 41% de segmentos de raíz produjeron brotes, con un promedio de 2.17 brotes por explante. Por otra parte, los segmentos de raíz transformada inoculados en posición horizontal 635 Cuadro 1. Efecto del tiempo de cocultivo y de la concentración bacteriana en la producción de raíces transformadas en segmentos de tallo de naranjo agrio. Table 1. Effect of co-culture time and bacterial concentration on production of transformed roots in sour orange stem segments. Tiempo de cocultivo (h) Concentración de la bacteria, células (mL−1) % de explantes con raíces 1×10 7 1×10 8 1×10 9 1×10 7 1×10 8 1×10 9 1×10 7 1×10 8 1×10 9 22.7 18.5 50.0 30.0 35.8 32.8 66.5 91.0 17.0 48 48 48 72 72 72 96 96 96 Raíces por explante, media±DE† 1.7 2.0 1.8 3.0 3.4 2.5 3.3 3.6 1.0 ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± 0.67 b 0.10 b 0.83 b 1.68 ab 1.50 a 1.20 ab 0.92 a 0.67 a 0.3 b † Medias con diferente letra en una columna son diferentes (Tukey, p≤0.05) ❖ Means with different letter in a row, are different (Tukey, p≤0.05). compound were added to bacterial suspension, although 200 µM showed an inhibitory effect (Table 2). This same phenomenon has already been reported for other A. rhizogenes-transformed species. In Brassica oleracea var. italica, frequency of explants with transformed roots is increased when using 50 mM acetosyringone, but this value is decreased when increasing concentration to 100 mM (Henzi et al., 2000). Number of roots per explant showed no significant differences among the four concentrations of acetosyringone (Table 2). Transformed roots kept in the dark exhibited greater growth (6.7±1.5 cm in 30 d), in comparison to the ones incubated under continuous light, which only grew 0.7±0.15 cm in the same period; this difference was significant according to the Mann-Whitney test. Despite displaying less growth, the roots incubated under continuous light stayed vigorous and turned green due to chlorophyll synthesis. Cuadro 2. Efecto de la acetosiringona en la producción de raíces transformadas a partir de segmentos de tallo de Naranjo agrio. Table 2. Effect of acetosyringone on transformed root production from sour orange stem segments. Acetosiringona, µM 0 50 100 200 † % de explantes con raíces 45.2 83.2 56.0 25.0 Raíces por explante, media±DE † 1.10 1.57 1.07 1.00 No hubo diferencias significativas (Tukey, 0.05) no significant differences (Tukey, 0.05). ❖ ± ± ± ± 0.10 0.13 0.08 0.00 There were 636 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 37, NÚMERO 6, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2003 no produjeron brotes en ningún tratamiento. Sólo se observó la aparición de tejido calloso en algunos de ellos, pero a los 60 d todos habían muerto. Los brotes mayores de 15 mm fueron recolectados y transferidos a medio sin reguladores del crecimiento, donde 55% creció y formó raíces, mientras que el 45% restante detuvo su desarrollo y sufrió necrosis. La eficiencia de enraizamiento obtenida en este trabajo puede considerarse alta y satisfactoria, ya que la baja tasa de enraizamiento de los brotes transgénicos es una de las principales limitaciones de los sistemas de transformación de cítricos basados en A. tumefaciens (Gutiérrez et al. 1997). Las plántulas mayores de 50 mm y con un sistema radical vigoroso se transfirieron a suelo (mezcla comercial de suelo estéril para macetas) y fueron mantenidas primero en una cámara bioclimática y luego en invernadero (Figura 1e). Algunas de las plantas mostraron un fenotipo alterado, con entrenudos cortos, hojas arrugadas y sistema radical muy desarrollado. La introducción de los genes rol de A. rhizogenes produce, en algunos casos, cambios fenotípicos, como el incremento en la capacidad de generar raíces y la reducción en el tamaño de la planta, alteraciones atractivas cuando se presentan en materiales usados como portainjertos (Christey, 2001), como en el naranjo agrio. Finalmente, el sistema de transformación desarrollado fue utilizado para la introducción del gen que codifica para la proteína de la cápside del VTC en tejidos de naranjo agrio; se obtuvieron tanto raíces (Figura 1f) como brotes (Figura 1g) transformados con dicho gen. Regeneration of adventitious shoots from transformed roots Transformed root segments inoculated up-right started to generate adventitious shoots on the upper end 15-30 d after transfer to two of the three regeneration media tested (Table 3) (Figure 1c). The highest frequency of shoot-generating explants was observed in medium with 5.0 mg L−1 BA and 1.0 mg L−1 ANA. Mean number of shoots per explant did not show significant difference between the two treatments that produced shoots. In the treatment with 10.0 mg L−1 BA and 2.0 mg L−1 ANA no response was observed at all, probably due to toxicity on tissues caused by such high concentrations of growth regulators. The efficiency of the BA-ANA combination for generation of transformed shoots in sour orange has been reported by Ghorbel et al. (2000), who worked with an A. tumefaciens -based transformation system. The efficiency of shoot generation from transformed root segments obtained for sour orange is lower to that observed in Mexican lime (Pérez-Molphe-Balch & Ochoa-Alejo, 1998), where 41% of root segments produced shoots, with a mean of 2.17 shoots per explant. On the other hand, transformed root segments inoculated horizontally did not produce shoots in any treatment. Only the formation of callous tissue was observed in some of them, but all were dead after 60 d. Shoots longer than 15 mm were collected and transferred to medium without growth regulators, where 55% grew and produced roots, while the remaining 45% arrested development and underwent necrosis. The rooting efficiency achieved in this study is considered high and satisfactory, since the low ratio of rooting in transgenic shoots is one of the major constraints to A. tumefaciensbased citrus transformation systems (Gutiérrez et al. 1997). Seedlings longer than 50 mm and with a vigorous radical system were transferred to soil (commercial mix of sterile soil) and kept first in a bioclimatic chamber and then under greenhouse conditions (Figure 1e). Some of the plants exhibited an altered phenotype, with short internodes, wrinkled leaves and over-developed radical system. The introduction of rol genes of A. rhizogenes produce phenotypic changes in some cases, such as an Caracterización de los tejidos transformados El crecimiento de las raíces en el medio de selección sin reguladores del crecimiento es ya una primera evidencia de la transformación. Para confirmarlo, se hicieron ensayos histoquímicos para detectar la actividad de gus en todos los materiales generados, así como pruebas de PCR y Southern blot en una muestra de los mismos. De las líneas de raíces presuntamente transformadas, 80% mostraron actividad de gus (Figura 1b). En cuanto a los brotes generados a partir de las mismas, 100% mostró actividad de gus (Figura 1d). Estos resultados contrastan Cuadro 3. Regeneración de brotes adventicios en segmentos de raíz de naranjo agrio transformada con la cepa A4/pESC4, cultivados en posición vertical en tres medios con BA y ANA. Table 3. Regeneration of adventitious shoots in sour orange root segments transformed with strain A4/pESC4, cultured in up-right position in three BA-ANA containing media. Tratamiento (reguladores del crecimiento en mg L−1) 2.5 BA + 0.5 ANA 5.0 BA + 1.0 ANA 10.0 BA + 2.0 ANA % de segmentos de raíz que generaron brotes adventicios 5.2 18 0 Brotes adventicios por segmento de raíz (media±DE) 1.12 ± 0.186 1.25 ± 0.162 0 CHÁVEZ-VELA et al.: TRANSFORMACIÓN GENÉTICA DEL NARANJO AGRIO USANDO Agrobacterium rhizogenes con los obtenidos al utilizar un sistema de transformación basado en A. tumefaciens, con el que se reporta 2.4% de brotes positivos para GUS en naranjo agrio (Gutiérrez et al., 1997). Los resultados con PCR fueron positivos, ya que se amplificaron fragmentos de 780, 517 y 1200 pb, correspondientes a los genes rolB, nptII y gus, en el ADN proveniente de una muestra de hojas gus positivas de plántulas transformadas con el plásmido ESC4. No se observó el fragmento de 450 pb correspondiente al gen virD1, por lo que se descarta que estos resultados hayan sido producto de la contaminación con A. rhizogenes (Figura 2a). El análisis Southern blot mostró la presencia de una señal de alrededor de 10 kb, que corresponde al gen nptII, en el ADN proveniente de cuatro líneas analizadas de raíces transformadas (Figura 2b). Finalmente, se analizaron mediante PCR seis líneas de raíces y cinco de hojas de plántulas transformadas con B249CP-pGA482GG, amplificándose en todas una banda de 720 pb, correspondiente a un fragmento del gen de la cápside del VTC (Figura 2c). Estas pruebas confirman la naturaleza transgénica de las raíces y plantas generadas. CONCLUSIONES Se desarrolló un sistema para la transformación genética del naranjo agrio usando Agrobacterium rhizogenes como vector. La mayor eficiencia se obtuvo al cocultivar segmentos internodales por 96 h con una suspensión bacteriana a una densidad de 1×108 células mL−1. La adición de acetosiringona (50 µM) a la suspensión bacteriana tuvo un efecto benéfico en la eficiencia de transformación. Las raíces transformadas mostraron un mayor crecimiento al ser mantenidas en la obscuridad. La regeneración de brotes adventicios a partir de las raíces transformadas se logró inoculando segmentos de 10 mm de longitud en posición vertical en medio adicionado con 5 mg L−1 de BA combinados con 1.0 mg L−1 de ANA. Este sistema se utilizó para introducir el gen que codifica para la proteína de la cápside del VTC en el naranjo agrio. Las plantas que expresan este gen podrían mostrar una mayor resistencia a la infección con este virus, como se ha observado en otras especies vegetales transformadas con cápsides virales (ReimannPhilipp, 1998). AGRADECIMIENTOS Los autores agradecen el apoyo financiero de la Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes (PIB-98-3 y PIBT-00-1) y del Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (31426-B). A este último se le agradece también las becas de posgrado otorgadas a N. ChávezVela y L. Chávez-Ortiz. Asimismo, agradecen a la Dra. June Simpson del CINVESTAV y al Dr. C.L. Niblett, de la Universidad de Florida, por proporcionar los plásmidos ESC4 y B249CPpGA482GG, respectivamente, y al MC. Manuel Robles González, 637 increase in root generating capability and reduction of plant size; these alterations may be desirable when they appear in materials used as rootstocks (Christey, 2001), as for sour orange. Finally, the transformation system developed was used to introduce the gene that codes for the CTV capsid protein into sour orange tissues. Both roots (Figure 1f) and shoots (Figure 1g) transformed with the gene were obtained. Characterization of transformed tissues. Root growth in selection medium without growth regulators is already a first evidence of transformation. In order to verify it, histochemical assays for the detection of gus activity were carried out in all generated materials, as well as PCR and Southern blot tests in a sample of them. Eighty percent of the putatively transformed lines showed gus activity (Figure 1b). Regarding shoots generated from these lines, 100% displayed gus activity (Figure 1d). These results differ from the ones obtained with an A. tumefaciens-based transformation system, where 2.4% of gus positive shoots is reported for sour orange (Gutiérrez et al. 1997). PCR results were positive, since 780, 517 and 1200 bp fragments were amplified, matching the rolB, nptII and gus genes, in a DNA sample from gus positive leaves from seedlings transformed with the ESC4 plasmid. The 450 bp fragment corresponding to the virD1 gene was not found; so, the possibility that the results had been caused by contamination with A. rhizogenes is discarded (Figure 2a). Southern blot analysis showed the presence of a signal of around 10 kb, corresponding to the nptII gene; in DNA from four lines of transformed roots (Figure 2b). Finally, PCR analysis was performed on six lines of roots and five of leaves from seedlings transformed with B249CP-pGA482GG; in all of them, a 720 bp band was amplified, which matches a fragment of the CTV capsid protein (Figure 2c). These tests confirm the transgenic nature of the roots and plants generated. CONCLUSIONS A genetic transformation system for sour orange was developed using Agrobacterium rhizogenes as transformation vector. The greatest efficiency was attained with co-culture of internodal segments for 96 h with a bacterial suspension of density 1×108 cells mL−1. The addition of acetosyringone (50 µM) to the bacterial suspension had a beneficial effect on the efficiency of transformation. Transformed roots displayed greater growth when kept in the dark. The regeneration of adventitious shoots from transformed roots was achieved by inoculation of 10 mm long segments in up-right position, in medium containing 5 mg L−1 BA combined 638 AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 37, NÚMERO 6, NOVIEMBRE-DICIEMBRE 2003 1 2 3 4 1 5 2 3 4 pb kb 1000 10 500 a b 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 pb 720 c Figura 2. a) Análisis PCR para verificar la presencia de los genes foráneos en ADN extraído de hojas de una planta de naranjo agrio transformada con el plásmido ESC4. Los genes amplificados fueron: Carril 1, rolb; Carril 2, nptII; Carril 3, gus; Carril 4, vird1; carril 5, marcador de peso molecular; b) Análisis Southern blot que demuestra la presencia del gen nptII en ADN genómico de cuatro líneas de raíces de naranjo agrio transformadas con el plásmido ESC4. c) Análisis PCR para verificar la presencia del gen de la cápside del VTC en raíces y brotes de naranjo agrio transformados con el plásmido B249CPpGA482GG. Carril 1: ADN de raíz no transformada. Carril 2: ADN de hoja no transformada. Carriles 3-8: ADN extraído de seis líneas de raíces transformadas. Carriles 9-13: ADN extraído de hojas de cinco brotes regenerados a partir de segmentos de raíz transformada. Figura 2. a) PCR analysis for confirmation of presence of foreign genes in DNA extracted from leaves from a pESC4- transformed sour orange plant. Amplified genes were: Lane 1, rolb; Lane 2, nptII; Lane 3, gus; Lane 4, vird1; Lane 5, molecular weight markev. b) Southern blot analysis that shows presence of nptII gene in genomic DNA from four lines of sour orange roots transformed with plasmid ESC4. c) PCR analysis to confirm the presence of CTV capsid gene in sour orange roots and shoots transformed with plasmid B249CP-pGA482GG. Lane 1: Untransformed root DNA. Lane 2: Untransformed leaf DNA. Lanes 3-8: DNA extracted from six lines of transformed roots. Lanes 9-13: DNA extracted from leaves from five shoots regenerated from transformed root segments. investigador del INIFAP Colima, por proporcionar el material vegetal utilizado en la investigación. LITERATURA CITADA Cervera, M., J. A. Pina, J. Juárez, L. Navarro, and L. Peña. 1998a. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of citrange: factors with 1.0 mg L−1 ANA. This system was used to insert the gene that codes for the CTV capsid protein into sour orange. Plants expressing this gene could show greater resistance to infection by this virus, as has been observed in other plant species transformed with virus capsids (Reimann-Philipp, 1998). CHÁVEZ-VELA et al.: TRANSFORMACIÓN GENÉTICA DEL NARANJO AGRIO USANDO Agrobacterium rhizogenes affecting transformation and regeneration. Plant Cell Reports 18: 271-278. Cervera, M., J. Juárez, A. Navarro, J.A. Pina, N. Duran-Vila, L. Navarro, and L. Peña. 1998b. Genetic transformation and regeneration of mature tissues of woody fruit plants bypassing the juvenile stage. Transgenic Research 7:51-59. Christey, M.C. 2001. Use of Ri-mediated transformation for production of transgenic plants. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology - Plant 37:687-700. Durón-Noriega, J., B. Valdez-Gazcón, J.H. Núñez-Moreno, y G. Martínez. 1999. Cítricos para el Noroeste de México. INIFAP. México. 155 p. Draper, J. and R. Scott. 1988. The isolation of plant nucleic acids. In: Plant genetic transformation and gene expression. A laboratory manual. Draper J., R., Scott, P. Armitage, R. Walden (eds). Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, pp: 199-236. Edwards, K., C. Johnstone, and C. Thompson. 1991. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 19:1349. Ghorbel, R., A. Domínguez, L. Navarro, and L. Peña. 2000. High efficiency genetic transformation of sour orange (Citrus aurantium) and production of transgenic trees containing the coat protein gene of citrus tristeza virus. Tree Physiol. 20:11831189. Gutiérrez-E., M.A., D. Luth, and G.A. Moore. 1997. Factors affecting Agrobacterium-mediated transformation in Citrus and production of sour orange (Citrus aurantium L.) plants expressing the coat protein gene of citrus tristeza virus. Plant Cell Reports 16:745-753. Hamill, J.D., S. Rounsley, A. Spencer, G. Todd, and M.J.C. Rhodes. 1991. The use of the polymerase chain reaction in plant transformation studies. Plant Cell Reports 10:221-224. Henzi, M.X., M.C. Christey and D.L. McNeil. 2000. Factors that influence Agrobacterium-rhizogenes mediated transformation of broccoli (Brassica oleracea L. var. italica). Plant Cell Reports 19:994-999. 639 Hooykaas, P.J.J., P.M. Klapwjik, M.P. Nuti, R.A. Schilperoot, and A. Horsch. 1977. Transfer of the A. tumefaciens Ti plasmid to avirulent Agrobacteria and Rhizobium ex planta. J. Genetic Microbiol. 98:477-484. Jofre-Garfias, A.E., N. Villegas-Sepúlveda, J.L. Cabrera-Ponce, R.M. Adame-Alvarez, L. Herrera-Estrella, and J. Simpson. 1997. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Amaranthus hypochondriacus: light- and tissue-specific expression of pea chlorophyll a/b-binding protein promoter. Plant Cell Reports 16:847-852. Murashige, T., and F. Skoog, 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth and bioassay with tobacco tissue culture. Physiologia Plantarum 15:473-479. Orozco-Santos, M. 1996. Enfermedades Presentes y Potenciales de los Cítricos en México. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, México. 150 p. Peña, L., M. Cervera, J. Juárez, A. Navarro, J.A. Pina, N. DuránVila, and L. Navarro. 1995. Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of sweet orange and regeneration of transgenic plants. Plant Cell Reports 14: 616-619. Peña, L., and L. Navarro. 1999. Transgenic citrus. In: Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry, Vol. 44 Transgenic Trees. Bajaj, Y.P.S., (ed.). Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heilderberg. pp: 39-54. Pérez-Molphe-Balch, E. and N. Ochoa-Alejo. 1998. Regeneration of transgenic plants of Mexican lime from Agrobacterium rhizogenes transformed tissues. Plant Cell Reports 17:591596. Reimann-Philipp, U. 1998. Mechanisms of resistance: Expression of coat protein. In: Plant Virology Protocols: From Virus Isolation to Transgenic Resistance. Foster, G.D. and S.C. Taylor (eds). Humana Press, Towota, New Jersey. pp: 521-532. Rocha-Peña, M.A., R.F. Lee, R. Lastra, C.L. Niblett, F.M. OchoaCorona, S.M. Garnsey, and R.K. Yokomi. 1995. Citrus Tristeza Virus and its aphid vector Toxoptera citricida. Threats to citrus production in the Caribbean and Central and North America. Plant Disease 79:437-445.