Ecosistemas altoandinos, cuencas y regulación hídrica

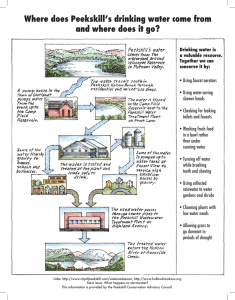

Anuncio

ENVIRONMENT/MEDIO AMBIENTE Ecosistemas altoandinos, cuencas y regulación hídrica High Andean Ecosystems, River Basins and Water Regulation L C Mecanismos de regulación hay varios: en las grandes llanuras de nuestro planeta, el agua es regulada principalmente a través de su almacenamiento temporal en acuíferos más o menos profundos. En la compleja geología de los Andes, la importancia de la regulación a través de aguas subterráneas profundas es limitada. En general, las opciones de regulación en montañas son pocas y frágiles. En las zonas de mayor altitud, existe almacenamiento y regulación de agua en forma de nieve y hielo, mientras que lagos y lagunas presentes a lo largo de la cordillera cumplen también una función de regulación natural. Pero el mecanismo de regulación más significativo en los ecosistemas altoandinos (páramo, puna con sus bofedales y turberas, y bosques donde estos todavía permanecen) es el almacenamiento de agua en los suelos que van dejándola ir por efecto de la gravedad a los riachuelos y ríos. Los suelos con alto contenido de materia orgánica, cobertura vegetal conservada y la microtopografía formada por la última glaciación, permiten almacenar gran cantidad de agua en la superficie del suelo o a poca profundidad. There are several mechanisms of regulation: in the great plains of our planet, water is regulated principally through temporary storage in more or less deep aquifers. In the complex geology of the Andes, the importance of regulation through deep groundwaters is limited. In general the options for regulation in mountains are few and fragile. In the zones of the highest altitude, storage and regulation of water exist in the form of snow and ice, while the lakes and lagoons present throughout the highlands also fulfill the function of natural regulation. But the most significant mechanism of regulation in the high Andean ecosystems (páramo, puna with its wetlands and bogs, locally known as bofedales, and forests where these still remain) is the storage of water in its soils from where it is released to the rivers and streams due to the effects of gravity. The soils with a high organic matter content, preserved vegetation cover and the micro-topography formed by the last glacial era, permits storage of great quantities of water on the surface and at shallow depths. as cuencas hidrográficas y sus ecosistemas nos brindan múltiples servicios ambientales, entre ellos los servicios hidrológicos, de suministro de agua en calidad y cantidad. Este último tiene a su vez dos aspectos importantes: el volumen de agua que “se produce” y que está en función del balance entre la precipitación y la evaporación, y la regulación hídrica, que está relacionada al almacenamiento. Este último aspecto es el que nos proporciona, en mayor o menor grado, un caudal relativamente constante, a pesar de la entrada irregular de la precipitación. atchments or basins and their ecosystems provide us multiple environmental services, among them the hydrologic service of providing water with quality and in quantity. The latter has at the same time two important aspects: the volume of water that “is produced” which is a function of the balance between precipitation and evaporation, and water regulation, that is related to its storage. This last aspect is the one that will give us, to a greater or lesser degree, a relatively constant flow despite the irregularity of precipitation. Entonces, cuando se dice coloquialmente que las “cabeceras de cuenca” son “fuentes de agua”, no significa que la parte alta de una cuenca tiene de por sí una capacidad de “producción” de agua mayor que alguna otra parte de la cuenca1 sino que, en los Andes, los ecosistemas de zonas altas así como los glaciares, Thus, when we say colloquially speaking that the “headwaters of the basin” are “sources of water”, it doesn’t mean that the high part of the basin has in itself a capacity of “production” of water greater than any other part of the basin1, but that, in the Andes, the ecosystems of the high zones, as well as the glaciers, are the ones that 1 1 No siempre en la parte alta de la cuenca es donde más precipitación se produce, por ejemplo en las cuencas amazónicas la precipitación es mayor en la parte baja de la cuenca. The highest part of the basin is not always the place where the most precipitation occurs; for example, in basins of the Amazon precipitation is greater in the lower part of the basin. Dialogue 21 ENVIRONMENT/MEDIO AMBIENTE son los que ofrecen un buen mecanismo de regulación. En zonas más bajas encontramos suelos de menor “calidad hidrológica”, que, además, generalmente están degradados en términos hidrológicos y nutricionales, es decir que han perdido capacidad de infiltración y de almacenamiento, por lo tanto su capacidad de regulación. Sin embargo, el mecanismo de regulación tan apreciado en las cabeceras de cuenca es tan frágil como lo son sus suelos. Si se les quita la protección que le da la cobertura vegetal, o peor aún cuando se les impacta directamente compactándoles o removiéndoles -situaciones que ocurren con la actividad agrícola y minera por ejemplo- estos suelos pierden rápidamente sus propiedades hidrológicas extraordinarias, muchas veces en forma irreversible cuando la acción implica el colapso de su frágil estructura. En general, los usos del suelo asociados con actividades antrópicas, tales como agricultura, pastoreo, manejo forestal y minería, e incluso el propio cambio climático, afectan negativamente varios aspectos importantes para el buen funcionamiento de la regulación hídrica (Buytaert et al., 2006). El mecanismo de regulación es mucho más que el almacenamiento en cuerpos de aguas superficiales. Describir este mecanismo sólo con el indicador de volumen de agua almacenado es tomar en cuenta solo una parte limitada del mismo. En su mayoría, los procesos hidrológicos que conforman la regulación en ecosistemas altoandinos, no son visibles. Posiblemente por ello, también son los menos estudiados y valorados. Y como en cualquier otra situación, para poder evaluar el impacto de X o Y acción, primero es necesario entender bien como funciona el proceso SIN esta acción. Si bien el estudio de los procesos hidrológicos en los ecosistemas andinos tiene todavía muy poca historia (Célleri et al., 2009), desde hace 10 años se viene estudiando intensivamente la hidrología de páramo en algunos sitios, especialmente en Cuenca (Ecuador) y Medellín (Colombia). Para la puna prácticamente no existen trabajos de investigación sobre sus procesos hidrológicos; aunque se han iniciado proyectos de investigación a través de la Iniciativa Regional de Monitoreo Hidrológico de Ecosistemas Andinos, red que tiene por finalidad incrementar y fortalecer el conocimiento sobre la hidrología de ecosistemas andinos para mejorar su gestión. En el debate sobre grandes proyectos mineros, buena parte de la discusión trata sobre almacenamiento, infiltración, drenaje, es decir, los caminos por donde fluye el agua. La propuesta de intervención en una zona y la evaluación de su impacto ambiental hidrológico no son completas sin un estudio profundo de estos mecanismos por los que transita el agua. La falta de conocimiento sobre el funcionamiento hidrológico de los ecosistemas altoandinos es una fuente importante de incertidumbre que limita la evaluación del potencial impacto de proyectos que alteran la hidrología y el nivel de debate al respecto. offer a good mechanism of regulation. In the lower zones, we find soil of less “hydrologic quality”, which, in addition, is generally degraded in hydrologic and nutritional terms, which is to say that it has lost its infiltration and storage capacity, and therefore, its capacity for regulation. Nevertheless, the mechanism of regulation so appreciated in the headwaters of the basins is as fragile as their soils. If the protection that the vegetation cover provides is eliminated, or even worse, if they are impacted directly by compacting or removal -situations that occur in agricultural and mining activity, for example- these soils rapidly lose their extraordinary hydrologic properties, mostly irreversibly when the action means a collapse of their fragile structure. In general, the land uses associated with human activities, such as agriculture, grazing, forestry and mining, and even climate change itself, affect negatively various important aspects of proper functioning of water regulation (Buytaert et al., 2006). The regulation mechanism is much more than storage in surface waters. To describe this mechanism only with an indicator of the volume of this stored water only takes into account a limited part of it. The majority of the hydrological processes that form the regulation in high Andean ecosystems are not visible. Possibly because of this, they are also the least studied and valued. And as in any other situation, in order to be able to evaluate the impact of X or Y action, it is necessary first to understand thoroughly how the process functions WITHOUT this action. Although the study of the hydrologic processes in the Andean ecosystems still has very little history (Célleri et al., 2009), in the last 10 years paramo hydrology is being studied intensively in some places, especially in Cuenca (Ecuador) and Medellin (Colombia). For the puna, practically no research on its hydrological processes exists; although some research projects have begun through the Regional initiative for Hydrological Monitoring of Andean Ecosystems, a network whose goal is the increase and strengthening of knowledge about the hydrology of Andean ecosystems in order to improve their management. In the debate about the large mining projects, a good part of the discussion deals with water storage, infiltration, drainage; that is, with the pathways along which the water flows. The proposition of intervention in a certain area and the evaluation of the hydrological environmental impact are not complete without a profound study of these mechanisms by which the water moves. The lack of knowledge about the hydrologic functioning of high Andean ecosystems is an important source of uncertainty that limits the evaluation of the potential impact of projects that alter the hydrology, as well as the level of debate with respect to this impact. POR/BY Bert De Bièvre / Luis Acosta Área de Cuencas Andinas/Area of the Andean Basins CONDESAN (Consorcio para el Desarrollo Sostenible en la Ecorregión Andina/ 22 Dialogue