Trafficking in organs, tissues and cells and trafficking in

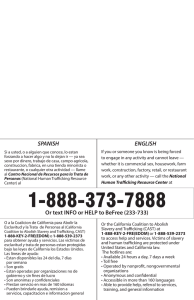

Anuncio