Constitutional Change in Latin America

Anuncio

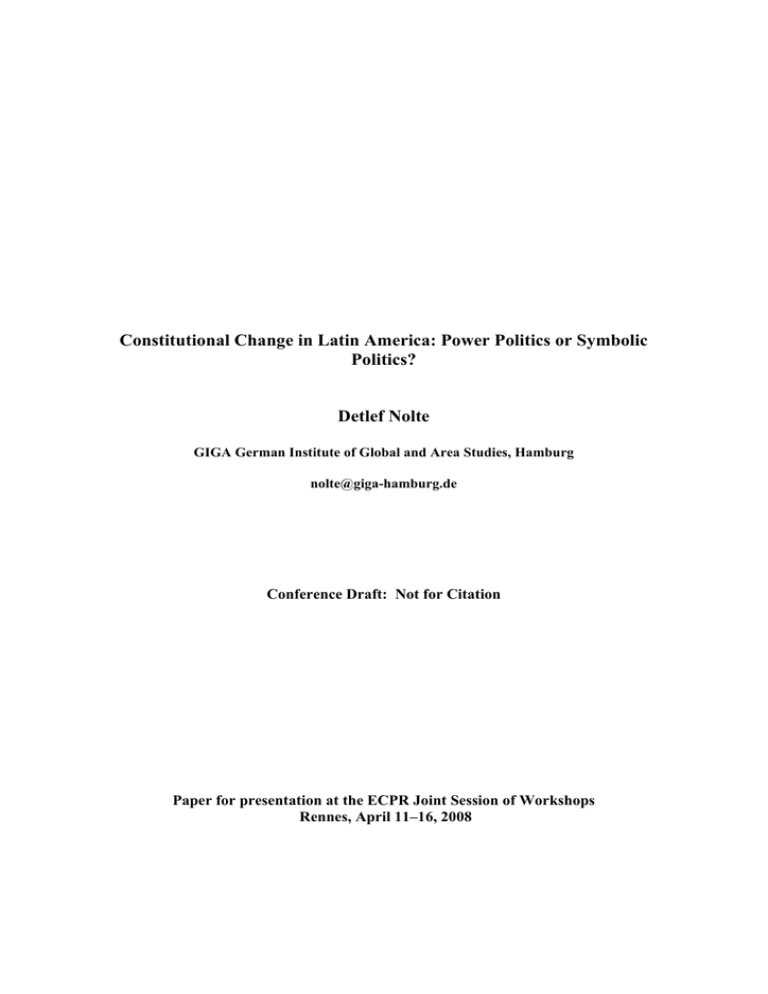

Constitutional Change in Latin America: Power Politics or Symbolic Politics? Detlef Nolte GIGA German Institute of Global and Area Studies, Hamburg [email protected] Conference Draft: Not for Citation Paper for presentation at the ECPR Joint Session of Workshops Rennes, April 11–16, 2008 2 ‘… en America Latina reina el fetichismos constitucional, la creencia un poco naïf o cándida de que con una gran reforma constitucional se puede crear el momento político necesario para construir una sociedad y un Estado estable y más igualitario’. 1 (Interview with the former President of the Colombian Constitutional Court and Dean of the Law Faculty of the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá, Eduardo Cifuentes) http://www.voltairenet.org/article149540.html ‘... la idea compartida es que un mejor diseño de los dispositivos e incentivos institucionales podría mejorar, y mucho, el funcionamiento de la democracia. ... a diferencia de lo que ocurría hace algunas décadas, las instituciones no son vistas como un reflejo secundario de lo esencial, sino como parte de lo esencial.’ 2 (PNUD 2004: 170) ‘… el problema de la relación entre Constitución y democracia en América Latina no reside tanto en la promulgación de nuevas Constituciones sino más bien en la aplicación efectiva de las ya existentes ... Esta es una vía más económica y moralmente más honesta que la reiterada reunión de asambleas constituyentes.’ 3 (Garzón Valdés 2000: 78) 1. Introduction Since the democratic transitions of the 1980s, most of the Latin American republics have reformed their constitutions at least once, and some have done it several times. Sometimes, the reforms have been quite limited with regard to their scope. But many times the constitutional reform processes have been very comprehensive, including a constitutional assembly and a plebiscite to validate the new constitution. New constitutions have been promulgated in Brazil (1988), Colombia (1991), Paraguay (1992), Peru (1993), Ecuador (1998), and Venezuela (1999). And the process of constitutional reforms continues in the twenty-first century: the Chilean constitution was fundamentally overhauled in 2005. In 2007 in three Latin American countries – Bolivia, Ecuador and Venezuela – constitutional assemblies drafted new constitutions. In all three countries the reform process has been highly contested. In Venezuela the controversial constitutional reform proposal elaborated by the 1 ‘… in Latin America constitutional fetishism prevails: the belief, a little bit naive or candid, that with extensive constitutional reform you can create the political momentum which is necessary to build a more solid and egalitarian society and state.’ (translation D.N.) 2 ‘… the prevalent idea is that a better design of the institutional provisions and incentives can improve, and very much so, the mode of operation of democracy … unlike what happened some decades ago, institutions are not perceived as a secondary reflection of the essential, but as part of the essential.’ (translation D.N.) 3 ‘... the problem of the relationship between constitution and democracy in Latin America does not consist so much of the promulgation of new constitutions but of the effective application of the existing ones … This is a more economic and a morally more honest way than the recurrent gathering of constituent assemblies.’ (translation D.N.) 3 Chavez-dominated Congress was narrowly defeated in a referendum in December 2007. In other countries such as Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru wide-ranging constitutional reforms are still being discussed. While in some cases the constitutional reforms have sought a redistribution of power between different political actors or the perpetuation of the power of certain politicians (permitting their previously constitutionally forbidden re-election), constitutional reforms have also been conceived of as a way out of a political impasse or an entrenched status quo. The latter conception is based on the vague hope that by changing the rules of the game or by including political promises in the constitution, politics would become re-legitimated in the eyes of the citizens. This paper aims to gain a better understanding of the causes, forms (scope), and consequences of constitutional reform in Latin America. It will provide an overview of constitutional reform in Latin America. First, it will systematically document the various constitutional reforms in Latin America since the 1980s, viewing Latin America from a comparative perspective with regard to constitutional reforms in other parts of world. The article will describe the different reform mechanisms in Latin America and the regulation density before and after the reform process. As a second step, it will systematise possible causes of constitutional reforms. This will be done first in a quantitative way, by investigating the relationship between constitutional rigidity and reform frequency. In the next step, the paper will analyse the length and regulation density of Latin American constitutions on the one hand, and the variation of these indicators during the timeframe investigated on the other. It will then differentiate between causal factors of constitutional change and provide some empirical illustrations. Subsequently, some general reflections about the reasons for constitutional reform in Latin America will be presented. The paper includes both empirical findings about the numbers and rates of constitutional reforms in Latin America and conceptual and qualitative thoughts based on the Latin American cases. It will contribute to the discussion about the causes and patterns of constitutional change by broadening the empirical base. Constitutional reform is an important topic not only in the OECD world and Central and Eastern European countries, but also in Latin America, which, as a region, has a long tradition of constitutional reforms. The present investigation demonstrates from a comparative perspective that Latin America is not so different from other regions, for example, Europe, with regard to the number of reforms in the 1990s. But the results display a great variation in terms of the yearly amendment rates in different Latin American countries. With regard to their rigidity or the 4 difficulty of reforming them, Latin American constitutions are perhaps slightly less rigid than in other parts of the world, especially Europe. In comparison with Europe, Latin American constitutions are quite lengthy: some contain more than 300 articles and more than 40,000 words. Alluding to other studies on constitutional change, we analysed in a preliminary way the impact of constitutional rigidity and constitutional length on the amendment rates. Concerning this particular Latin American sample, only a small – but not significant – positive correlation between the amendment rate and the length of a constitution could be found, and there was no evidence as to the correlation between the rigidity and the amendment rate of the constitutions. Thus, this study’s results are in tune with recent studies on constitutional change in other parts of the world. In a subsequent step more causal factors that could explain constitutional reform in Latin America were identified: the elimination of authoritarian legacies in the constitution, good governance reforms, symbolic politics, the constitutionalisation of policies and subsequent policy-related constitutional reforms, and power politics by means of constitutional reforms. It is expected that it will be difficult to identify a common reform pattern for Latin America. The study concludes with some reflection about future research topics. 2. Constitutional change in Latin America: a new research topic The subject of constitutional change in developed democracies has seldom been analysed from a comparative perspective (Lorenz 2004; 2005). There are few studies focusing on the rigidity of constitutions, their length / regulation density, and the frequency of reforms (Lutz 1994; Lijphart 1999; Lorenz 2004; 2005; Rasch/Congleton 2006). In this context it is not so surprising that there is also lack of studies on constitutional change in Latin America. 4 The exception is an unpublished paper by Negretto (2006) which analyses constitutional stability and constitutional replacements in 18 Latin American countries between 1946 and 2000, including both democratic and authoritarian constitutions. Constitutional stability is defined as durability. The lifespan of a constitution is the length of time that passes between its enactment and its formal replacement by another constitution. 4 But it seems that the topic is attracting more interest. At the last (2007) APSA (American Political Science Association) and LASA (Latin America Studies Association) conferences, constitutional reform processes in Latin America were discussed in two panels. For the next LASA conference in 2009 (Rio de Janeiro), at least two panels on the this topic have been proposed. 5 This means that the longer a constitution survives without being replaced, the more stable it is. 5 With regard to the empirical findings (Negretto 2006), political instability and regime change are, not surprisingly, highly correlated with constitutional stability. The same is true for transformations of the party system (as a result of the emergence of new political actors) and anti-government demonstrations. In addition, institutional factors embedded in the constitutional design have an important effect on the survival of constitutions: Bicameralism as well as the existence of a body responsible for interpreting the constitution reduce the risk of constitutional replacement. On the one hand, bicameralism may provide representation to a larger number of actors, who therefore have no interest in changing the constitution; on the other hand, bicameralism makes it more difficult to reach an agreement on the replacement of the existing constitution. 6 Constitutions can be altered by means of amendment, replacement, judicial interpretation, 7 and legislative revision (Lutz 1994). But sometimes it is not so easy to make a clear-cut differentiation between replacement and amendment: For example, the Chilean reform of 2005 deleted most of the authoritarian elements of the Pinochet Constitution from 1980, but it did no constitute a complete replacement. On the other hand, Brazil is undergoing a process of permanent constitutional amendment. Between 1988 and 2007 the constitution was reformed not less than 62 times, or on average 3 times each year. Its length increased from approximately 40,000 words in 1988 to about 50,000 words in 2005. Thus, in the Latin American case, it is not sufficient to focus comparative research only on constitutional replacements or major constitutional reforms; it is rather necessary to also include piecemeal reforms in the analysis. In contrast to Negretto’s (2006) study, this analysis uses a broader focus in looking at constitutional change in Latin America, including not only constitutional replacement but also constitutional amendments. It spans the current democratic period (1978–2007). 5 The dataset includes 990 observations representing 62 constitutions, 44 of which were replaced during these years, and 18 of which were still surviving as of 2000. Of the 62 constitutions, 26 were enacted in democratic and 36 in non-democratic years. Neither amendments to nor the temporary suspension of constitutions are included here as events of constitutional failure (Negretto 2006). 6 On Latin American bicameralism see Llanos/Nolte (2003). 7 The different judicial adjudication systems in Latin America are analysed by Navia / Ríos-Figueroa (2005). 6 3. Constitutional change in Latin America: empirical findings Constitutions were replaced quite often in Latin America during the twentieth century. The mean number of constitutions adds up to 5.7 for 18 Latin American countries (see table 1 in the annex). The average duration of Latin American constitutions has been 28.7 years, but with great variations – for instance, in the cases of Chile and Colombia, with more than 50 years, and Venezuela and Ecuador, with 6 and 13 years respectively. Some constitutions, such as the Mexican constitution of 1917 or the Argentinian constitution of 1853 (which was reformed in terms of some basic aspects in 1993), are quite time-honoured. Do Latin American countries change their constitutions more often than countries in other parts of the world? A recent study (Lorenz 2005: 339) reveals that 32 of 39 established democracies 8 amended their constitution between 1993 and 2002. The average rate amounted to 5.8 reforms in ten years. Moreover, three states (Switzerland, Finland and Poland) promulgated new constitutions. If we take a look at Latin America for the same time period (1993–2002) – without differentiating between liberal democracies and more illiberal varieties of political systems – there were three constitutional replacements (Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela) and 16 out 18 countries amended their constitution (see table 2 in the annex). The average rate amounted to 8.6 reforms in ten years (including amendments and replacements). If we exclude Mexico and Brazil – both countries account for a high percentage of the amendments – the average is 4.7. There was a total of more than 700 reforms of single articles (the same article could have been reformed various times) in this period (not counting constitutional replacements). So at first glance, from a quantitative perspective, constitutional change in Latin America is not so different from other world regions, for example, Europe. But Latin America itself presents a great variety of constitutional reform patterns (see table 2 in the annex). Some countries – such as Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras and Mexico, and to a lesser degree Chile and Colombia – have been going through a permanent reform process. Other countries – such as Argentina, the Dominican Republic and Guatemala – have rarely reformed their constitutions since the return to democratic rule. These constitutions have a high level of stability. Paraguay and Venezuela replaced their constitutions once in 1992 and 1999, but passed no other reforms or amendments afterwards. In the Paraguayan case, the 1993 constitution stipulated that any reform would be blocked for 3 (partial reform) or 10 (total reform) years. In Venezuela a far-reaching reform proposal was defeated in a plebiscite in 2007. 8 The sample includes four Latin American countries: Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, and Uruguay. 7 Until now, this discussion has focused on the period from 1993 to 2002 without taking the democratic quality of the regime in question into account. Unfortunately, illiberal democracy has become the dominant regime type in contemporary Latin America (Smith / Ziegler 2008). In 2000 there were six liberal democracies and nine illiberal democracies; another three countries were classified as illiberal semi-democracies, as repressive semi-democracies, or as moderate non-democracies in the terminology of Smith / Ziegler (2008). The analysis in this paper is based on the risky assumption that the constitutional reform process is not decisively hampered or adulterated in illiberal democracies and liberal /illiberal semi-democracies because an open violation of the constitutional procedures (such as serious manipulations of an election) would disqualify the regime as a democracy or semi-democracy. 9 So as a first step, the yearly amendment rates (taking the example of Lutz 1994) per country were calculated by adding liberal and illiberal (semi-)democratic periods for the years 1990–2007. 4 3,5 3 2,5 2 1,5 1 0,5 0 3.39 3.44 1.65 1 0 0 0.28 0.06 0.11 0.17 0.17 0.22 0.22 1.22 0.44 0.5 0.53 G ua te Pa m a ra la gu (1 ay 996 (1 99 200 7 220 )* D 07 om in Arg )** ic an en t R ina ep ub Pa lic na m U ru a gu Ec ay ua do B r N oliv ic a ia El rag Sa u a lv Pe ad ru or (1 99 C 3- hi 20 le 07 C C os )** ol om ta R bi H ic a ( 1 ond a 99 u 1- ra 20 s 07 ) M ** ex ic o B ra zi l Average number of changes per year Chart 1: Amendment rates (yearly) in Latin America, 1990-2007 * Between 1991 and 1995 non-democracy / repressive semi-democracy ** Countries that passed a new constitution at the beginning of the particular period Venezuela has been excluded because the only (1999) reform did not comply with the legal prescriptions. The results display a great variation concerning the yearly amendment rates; Mexico and Brazil are outliers, with 3.4 amendments per year. This distribution of amendment rates in the Latin American sample will complicate subsequent statistical analysis. 9 There is also a pragmatic argument. If we take the period since 1978, we can only identify a small number of clear-cut liberal democracies in Latin America (see table 3 in the annex).In the future the author will compare constitutional reform processes and patterns in liberal and illiberal democracies as well as in liberal / illiberal semi-democracies in order to corroborate our assumption. 8 The significant number of constitutional reforms in some Latin American countries as well as the considerable variation in this paper’s Latin American sample with regard to the number of reforms could be a hint that different reform procedures cause the variation in the reform patterns. Thus, the discussion will now take a closer look at the reform procedures stipulated in the constitutions. To begin with, it should be mentioned that three (Colombia, 1991; Peru, 1993; Venezuela, 1999) out of five cases of constitutional replacement since 1990 have occurred outside of the pre-established procedures. (These cases will be disregarded in the statistical analysis). In Colombia’s March 1990 parliamentary election a reform movement resulted in another non-binding ballot paper being put on the table (the so-called ‘séptima papeleta’) to consult the citizens about the need / desire for a constitutional reform. While electoral participation was low, 90 percent voted in favour of the reform proposal. In the presidential elections of May 1990 another ballot could be cast about convening a constituent assembly. Again, 90 percent voted in favour. After the Supreme Court decided that the reform process was not unlawful, the members of the constituent assembly were elected in December 1990 and a new constitution was promulgated in July 1991. In Peru in April 1992, the democratically elected president Alberto Fujimori dissolved Congress and regional governments, intervened in the judiciary, and shut down the Constitutional Tribunal. After massive pressure from Latin American neighbour countries and the Organization of American States (OAS), President Fujimori convened elections for a constituent assembly in November 1992. The most important opposition parties boycotted the election. Hence, a compliant assembly passed a reform proposal that concentrated much power in the presidency and abolished the Second Chamber. In October 1993 the reform proposal won by a small margin (52 percent). In Venezuela the newly elected (1998) president Hugo Chavez pushed through the election of a constituent assembly (after a positive vote of support in a referendum) to alter the power balance and to disempower Congress where the government did not command a majority. This kind of constitutional reform mechanism was not envisioned in the constitution of 1961. Ultimately, Chavez was successful in altering the political landscape of Venezuela by creating new political institutions and using the momentum of institutional reform to dominate the political agenda. These examples demonstrate that in some Latin American countries not only the constitution but also the rules for reforming the constitution are alterable. In a region with a 9 strong plebiscitary tradition it is always easy to invoke the will of the people, putting aside procedural formalities. There are different paths to constitutional reform in Latin America (see table 4 in the annex). All involve the parliament (most constitutions demand a two-thirds majority), some stipulate a constitutional assembly – at least in the case of a complete overhaul / replacement – and some require the citizens to consent in a plebiscite to the reform proposal. Uruguay is the only case where a constitutional reform by referendum is feasible (article 331 A) without any previous participation by parliament. Argentina is the only case that stipulates a constituent assembly for each kind of constitutional reform. In another five countries (Bolivia, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Venezuela) only a total reform requires a constituent assembly. In four countries (Guatemala, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela) each constitutional reform must pass the test of a referendum; in another six countries a referendum could be called under certain conditions. Mexico is the only country where the state parliaments of the federation have to approve the constitutional reforms (the same mechanism applied in Venezuela under the 1961 constitution). In two countries – El Salvador and Bolivia (until 2004) – two different legislatures had to vote on the reforms proposal. From a comparative perspective, how difficult is it to reform the constitution in Latin America countries? As a first approximation at answering this research question here, the analytical tools devised by Lijphart (1999), Lorenz (2004; 2005), and Rasch/Congleton (2006) were used to measure constitutional rigidity in Latin America. Afterwards, these scores were compared with the results of other studies that predominantly deal with constitutional reforms in developed democracies. There are two basic approaches to defining the rigidity of a constitution. Both refer to the difficulty of reforming the constitution. While the first approach focuses on the majorities that are necessary to reform the constitution (simple majorities or supermajorities), the other approach counts the number of veto points in the amendment process where a constitutional reform proposal could be blocked. There is also a third approach which combines veto points and majorities. Lijphart (1999) advocates for the first approach. He uses a four-point scale to measure constitutional rigidity: (1) approval by an ordinary majority; (2) approval by less than twothirds majority but more than an ordinary majority (including an ordinary majority plus a referendum); (3) approval by a two-thirds majority; (4) approval by a more than two-thirds majority, or a two-thirds majority plus approval by the state legislature. The analytical tools of 10 Lijphart (1999), with some minor revisions, have been used here. When alternative methods can be used, Lijphart counts the least restraining method. But in some Latin American countries, it is not so clear what the least restraining method actually is. The selection of a method depends on the reform strategy and the legislative majority. When it was not possible to make a clear-cut decision (for example, for Peru and Chile) for this paper’s analysis, the mean of the different options / values was counted. In the cases of a two-thirds majority plus a referendum an extra medium point was given (0.5), because a referendum constitutes one more threshold. As Latin America demonstrates, governments with a parliamentary majority can loose referenda. In Lijphart’s (1999) study, when different rules apply to different parts of the constitution, the rules pertaining to amendments of the most basic articles of the constitution have been counted. Because the present analysis is focused on the whole spectrum of constitutional reform in Latin America, it includes scores for both basic and minor revisions of the constitution. In most cases there is no difference with regard to the rating. For a better comparison with the results of other studies, the original scoring of Lijphart as well as this study’s revised score board have been included in the analysis. Rasch/Congleton (2006) represent the second approach to measuring constitutional rigidity. They count the number of veto points, defined as the number of governmental veto players plus an additional point if an intervening election is required and another if a referendum is normally used to ratify constitutional amendments. The number of governmental veto players is coded as 0 through 3, with a single point awarded for each centre of institutional authority beyond parliament that must agree to a proposed amendment: bicameral, presidential, and federal. This study has adopted Rasch/Congleton’s (2006) classification but has changed the coding rule, starting with 1 for parliamentary approval only and progressing to a maximum of 4. Lorenz (2004; 2005) combines the logic of veto points and voting majorities. 10 To measure the constitutional rigidity, she adds the scores for the required majorities in the requisite political arenas (veto points), including referendums. A legislature has to be assigned a score twice if it has been newly elected between two votes. Lorenz modifies the original Lijphart scale by treating a three-fifths majority like a two-thirds majority (3.0 points). Although this author is not convinced of the value of this modification, it has been adopted here in the interest of being able to compare this paper’s research results with the outcomes of 10 In a certain way, the complicated index of difficulty for amendment processes created by Lutz (1994) also combines veto points /arenas and majorities. The index is very intricate. It identifies 68 possible actions that could in some combination be used to initiate and approve constitutional amendments. Together they cover the combination of virtually every amendment process in the world. 11 other studies. A constitutional court, a government, or the president are assigned 1.0 (for a simple majority vote) when they explicitly have to consent to an amendment. Lorenz’s (2005) argument for how a referendum should be counted is not consistent (and her reference to Lijphart’s scoreboard is mistaken). She proposes 2.0 for an ordinary majority and 3.0. for a two-thirds majority. In contrast, this author thinks that an ordinary majority should be given 1.0. Based on the Latin American experience, the author does not agree with the assessment that a vote on the declaration of a need to amend the constitution should be scored with half of the normal points for the respective action. In Latin America these votes have repeatedly been highly contested. Moreover, the threshold for a positive vote to start the reform process is generally very high (two-thirds majority). How does the rigidity of Latin American constitutions compare with other countries and regions (see table 5 in the annex)? On average, constitutional reforms in Latin America have to pass two veto points. In Lijphart’s (1999) study, which covers 36 democracies (1945–1996; including Costa Rica and Colombia), the mean index of constitutional rigidity is 2.6 and the median 3.0 points. Lorenz’s (2004) study of 24 mainly European democracies (1993–2002) results in a mean of 2.8. With regard to this study’s sample of 18 Latin American countries (1978–2007), the mean is 2.6 (2.5 for minor reforms) and the median 3.0. Applying the index of Lorenz (2004; 2005), this author has calculated a mean of 4.3 for this paper’s Latin American sample, compared to a mean of 4.85 for a sample of 39 countries in the case of Lorenz (2005). Thus, from a comparative perspective Latin American constitutions are not so different with regard to their rigidity; they are slightly less rigid than those in other parts of the world, especially Europe. In his analysis of 50 American state constitutions and 32 national constitutions, Lutz (1994) confirmed his hypothesis that the more difficult the amendment process, the lower the amendment rate. In contrast to Lutz’s (1994) findings, in Lorenz’s (2004; 2005) study the hypothesis that institutional rigidity has an impact on the frequency (and scope) of constitutional reforms has not been statistically substantiated. There is a weak statistical correlation between regulation density and the frequency of reforms, but the results are contradictory when older and newer democracies are compared. The Rasch/Congleton (2006) analysis, covering 19 OECD countries (based on the amendment rates of Lutz), suggests that the number of veto points has a systematic effect on amendment rates. In this study’s Latin American sample, no evidence that could confirm the Lutz hypothesis could be found. There 12 were no statistically significant results 11 concerning the correlation between the rigidity and the amendment rate of the constitutions. Kendall’s tau-a was used to calculate the correlations. Table 1: Constitutional rigidity and amendment rates amendment rate (number of reforms per year) 0,0074 (sig. Level:1) -0.1544 (sig. Level: 0.3859) -0.1618 (sig. Level: 0.3757) 0 (sig. Level: 1) Lijphart (minor reforms) Lijphart (minor reforms, revised index) veto points Lorenz What has the impact of constitutional reforms been with regard to the volume and the number of regulations included in the constitution? Have the constitutions become leaner? Have the reforms just replaced parts of the constitutions, or have they added new regulations? Some Latin American constitutions are quite voluminous, containing more than 300 articles; Colombia and Honduras are the absolute top scorers with 372 and 379 articles respectively. But other constitutions are quite smart with regard to the number of articles: some of the older constitutions, such as the Argentinean and Mexican constitutions, contain less than 150 articles. The same is true of the Chilean and the Dominican constitutions. But the number of articles only partially captures the number of regulations included in the constitution, because some articles could be quite lengthy and include many sub-articles. For example, in the Mexican constitution, article 27 on the use of land and natural resources includes 20 quite substantial sub-articles. Article 123 on social security covers several pages and includes more than 40 sub-articles. Table 2:Latin American Constitutions: number of articles Number of articles Frequency 100–149 150–199 200–249 250–299 300–349 350–399 4 2 2 5 2 3 There are different indicators for measuring the length and regulation density of the constitutions: the number of articles, the number of words (Lutz 1994) or lines, and composite indices based on the aforementioned indicators. Following Lorenz (2004), the present study has calculated the following index: the number of articles has been divided by 100 and the 11 For this calculation Mexico and Brazil were excluded because of their extreme amendment rate in comparison with the other countries observed. 13 number of words by 10,000, with both values then added together. 12 The main source was the Political Database of the Americas 13 ; in a few cases other sources were also used. 14 While Lorenz (2004, 2005) has based her analysis on the corresponding English translations of the constitutions, this study has used the original Spanish or Portuguese (Brazil) versions, because with regard to the official language, the present study’s Latin American sample is quite homogenous. 15 This study is interested in the quantity and quality of constitutional change in Latin America throughout the current democratic period (until 2007). Therefore the first point of measurement is the constitution in force at the beginning of the democratic transition. This constitution could be the former democratic constitution suspended during a dictatorship (Uruguay) or a constitution adopted during a military dictatorship (Chile) or in a transition process (Brazil). The other point of measurement is the most recent (2007) text of the constitution (depending on the availability of data). Whenever a new constitution was promulgated or a major constitutional overhaul occurred during the period of investigation this text has been included as another point of measurement. Only the words in the text of the constitution have been counted. The headline and the preamble, the transitory articles, 16 the derogatory articles, and the phrases related to technical aspects regarding the derogated articles, the legislative basis of the derogation or substitution, and other aspects which are not related to the regulatory content of the constitution have been excluded. On average, the regulation density is quite high in Latin America (see table 6 in the annex). Lorenz (2004) has calculated a mean (articles plus lines) of 2.9, and the highest values (4.9 and 5.8) refer to Sweden and Portugal. In Latin America the regulation density (articles plus words) was 5.0 at the end of the period of investigation. By far the highest values refer to Brazil, Colombia, and Venezuela (7.4, 7.9, 6.9). In the case of Mexico, the relatively low number of articles conceals many sub-articles and paragraphs. Therefore, the constitution of Mexico includes more words than the constitution of Colombia, which has nearly three times the number of articles. 12 Lorenz (2004) divides the number of articles by 100 and the number of lines by 1,000 and adds both values. This author prefers the articles/words index principally from a pragmatic point of view; it makes it easier to compare the texts of constitutions from different Internet sources. Moreover, Lorenz (2005: 352) has found a strong correlation between words and lines. 13 http://pdba.georgetown.edu/ 14 Such as the Biblioteca Virtual Miguel Cervantes (http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/portal/constituciones) and the Constituciones Iberoamericanas de la Universidad Carlos III in Madrid. http://turan.uc3m.es/uc3m/inst/MGP/consibam.htm 15 The author compared some English and Spanish versions of Latin American constitutions with regard to the number of words of the constitution. The differences were minor. 16 In the case of Panama the disposiciones finales have also been included because they refer to the channel treaties 14 If we compare the constitutions at the beginning and the end of the period of investigation (depending on the availability of data), the texts of the later constitutions are without exception more voluminous and the regulation density is higher. Therefore, during the reform process the volume of text and the number of articles have not been cut down. This could be interpreted as an inclusion of more regulations in the constitution. In nearly all cases where new constitutions were adopted (Paraguay 1992, Argentina 1993; Ecuador 1998; Venezuela 1999), the text of the new constitution includes more articles and exhibits a major regulatory density (articles/words). An exception is Peru, where the new constitution (1993) adopted after Fujimori’s autogolpe was much leaner than the previous constitution. Is there a statistical relationship between the regulation density and the number of reforms? In his analysis of 50 American state constitutions and 32 national constitutions, Lutz (1994) found a strong relationship between the length of a constitution (counting the words) and its amendment rate. 17 Lutz’s (1994) results with regard to the impact of the rigidity and length of constitutions on their amendment rate could not be verified by Lorenz (2005) in her sample of fully established democracies in the period 1993–2002. With regard to this study’s Latin American sample, only a small – but not significant – positive correlation (Kendall’s tau-a: 0.2857 ; significant at 15%) 18 between the amendment rate and the length of a constitution could be found. In future it would be useful to analyse which subjects make the constitutions so lengthy/voluminous and which parts have been reformed. Alternative explanations for constitutional change should also be sought, including factors that capture the political dynamics of constitutional reform processes. Perhaps it would be useful to act on the assumption of different reform patterns and causes. 4. Explanations of constitutional change in Latin America What have been the reasons for constitutional change in Latin America since 1978? There are at least five possible interpretations that are not mutually exclusive. 17 According to Lutz’s (1994) analysis, the variance in amendment rates is largely explained by the interaction of the length of the constitution (in words) and the difficulty of the amendment process (measured by an index of institutional devices). 18 For this calculation only 15 out of 17 observations were used because there was no data for the index-variable (length / regulation density of constitution) available for Mexico and Costa Rica. The correlation between amendment rate and length of constitution was calculated with Kendall’s tau correlation for two reasons: Pearson couldn’t be used because one of his key assumptions (normal distribution) was violated by this study’s two variables, which were due to the small sample. 15 First, the transition to democracy and the authoritarian legacies has made it necessary to reform the constitution or to pass / adopt a new constitution. Second, within the framework of an international discourse about good governance and a growing awareness of the importance of institutional design, Latin American governments have embarked on a course of constitutional reforms to improve the performance of the political systems. Third, the reforms are purely symbolic, because there is no consensus on major political issues and there is a blockade with regard to major policy reforms. The focus on a constitutional reform can deflect the political frustrations of the citizens with regard to material reforms. Fourth, in some countries many articles of the constitution refer to policies (in contrast to political rights and rules). Therefore, a change of policies requires a change of the constitution. Fifth, the reform of the constitution is part of power politics. On the one hand, the new rules included in the constitution can benefit some actors (for example, a new re-election clause for the presidency). On the other hand, a newly elected constituent assembly can compete with the acting parliament, claiming a superior legitimacy, and in extreme cases replace it. Next, the discussion will analyse constitutional change in Latin America in a qualitative and descriptive way with the aim of making a first assessment of how far the different causal interpretations presented are reflected in the reform processes. 1. Democratic Transition: One possible hypothesis to explain constitutional reforms in Latin America refers to the transition process. After a period of authoritarian rule, the new democratic governments have had to create new institutions or to reform the existing political structures. The Latin American experience is mixed, but there are many examples to substantiate the hypothesis. In Latin America, only a few transition processes have started with the adoption of a new constitution (Ecuador, 1978; Honduras, 1982; Brazil, 1988). In Paraguay the constitution was reformed some years after transition (1992). Many countries reverted to former democratic constitutions that had been abrogated during military rule (Argentina, Bolivia, Peru, Uruguay). In some countries the adoption of a new constitution was part of a 16 transition process that subsequently took several more years (El Salvador, 1982; Guatemala, 1983; Nicaragua, 1987). Chile, Peru, and the Dominican Republic are special cases. As a result of internal and external pressure to institutionalise its rule, the Chilean military junta presented a new constitution in 1980 that would legitimise the regime and constrain a future democratic government. 19 The constitution was ratified in a referendum that did not comply with basic democratic standards. Nevertheless, based on the constitution and repressive practices, the military managed to stay in power until March 1990. In 1988 General Pinochet’s plot to obtain pseudo-democratic legitimacy for his rule and to stay in power was defeated in a plebiscite. Under pressure from the triumphant opposition, the authoritarian government accepted reforms to the constitution that eliminated some of its non-democratic elements. The amendments were voted on in another plebiscite (1989). The authoritarian government had crafted a constitution to hedge the socio-economic transformations that had been imposed on Chilean society since 1973 against future reform efforts. The constitution comprised so-called ‘authoritarian enclaves’ (Garreton) and conferred a special status on the armed forces. The electoral system made it difficult to win a clear majority in both houses of Congress and gave advantages to the first minority. While Pinochet lost the plebiscite 1988, he held the command of the armed forces until March 1998. In this difficult context, the democratic governments since 1990 have tried to dismantle the Pinochet constitution step –by step, starting with the democratisation of the local governments. Finally, in a last reform thrust in 2005, nearly all remaining authoritarian elements of the constitution were eliminated. In Peru, the constitution reluctantly hammered out by Fujimori 1993 eliminated many elements of political decentralisation and political participation in sub-national territorial units. Thus, some of the reforms after the hasty resignation of Fujimori in 2000 concerned the rights of the regions and municipalities. The 1994 presidential election in the Dominican Republic, won by Joaquín Balaguer, was tainted by widespread electoral fraud. As a solution to the institutional crisis, the constitution was reformed: Immediate presidential re-election was foreclosed, and in a transitory article the presidential period was reduced from four to two years. By this means, future presidential and parliamentary elections were also separated. 2. Institutions Matter: The quotation at the beginning of this article from the UNDP study on democracy in Latin America is persuasive. Institutions matter in Latin America, at least in the public and academic discourse. Moreover, international financial organisations such as the 19 On the origins and making of the Chilean constitution of 1980 see Barros (2002). 17 World Bank or the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) have stimulated governments – by offering financial initiatives – to reform basic political institutions. What is more, the IADB has financed academic studies on the operation and performance of democratic institutions in Latin America as well as on possible and desirable reform paths (for example, Payne et al. 2007; IADB 2006). But one has to concede that the reforms have not always reflected the advice of academics and international financial institutions. There have been at least four reform cycles since the late 1980s, which have often overlapped and which have been reflected in constitutional reform processes. The first reform cycle referred to the decentralisation of political functions and power (including the democratisation of sub-national administrative structures). Constitutional articles that define the administrative state structure or the territorial allocation of power, financial resources, and state functions were often reformed. The second cycle concerned the reform of judicial power and the creation of new institutions of horizontal accountability. So in some cases the judicial independence was bolstered. Some countries created new specialised constitutional courts (Lösing 2001; Navia / Ríos-Figueroa 2005); sometimes the reform of the criminal code or the introduction of new criminal law proceedings (with independent public prosecutors) made it necessary to reform the constitution. In other cases, new institutions for the protection of citizens rights were created (ombudsman / defensor del pueblo). Another reform cycle concerned the promotion of political participation by changing the electoral system or by creating new participatory channels (direct democracy). The fourth reform cycle encompassed all the constitutional changes supporting the neo-liberal economic reforms of the 1990s (deregulation, privatisation of state enterprises, social security reforms, etc.). If we were to take a closer look at the constitutional reforms in Latin America in the 1990s, we would expect to find certain reform clusters around the topics of decentralisation, judicial reform, participation, and neo-liberal institutional reforms. 3. Symbolic Politics. The quotation from Garzón Valdés (2000) at the beginning of this article describes a basic problem in many Latin American countries: On the one hand, there are (too) many laws as well as quite meticulous and comprehensive constitutions. On the other hand, there is a widespread lack of respect for the law. This may explain why the constitutions sometimes include all kinds of political rights and obligations that are quite difficult to comply with and often disconnected from the social and political reality of the country. For instance, article 22 of the 1991 Colombian constitution delineates that ‘peace is a right and an obligation that has to be complied with mandatorily”. And article 52 recognises 18 the right of each person to recreation, practising sport, and using his leisure time. Perhaps nobody expects that these norms will be put into practice. Thus, on the one hand, the real effect of constitutional reforms may be quite limited. On the other hand, constitutional reforms or new constitutions could be a cheap way for politicians to deliver some symbolic goods, thus avoiding the necessity of carrying out real policies. It may therefore be interesting to analyse more precisely the political situation before and after constitutional reforms. Major reforms such as those undertaken in 1991 in Colombia and 1998 in Ecuador had little long-term impact on the political dynamic in these countries. If the Freedom House scores – a crude indicator for democratic quality – are taken into account, there are only a few cases of major constitutional reforms (for instance, the cases of democratic transitions) where there has been a positive change in the scores one year after the reform compared with the year before the reform.. With regard to the long-term effects (five years after the reforms), there are many more additional factors that have had an influence on the Freedom House scores. Table 3: Democratic quality before and after major constitutional reforms Country Argentina Bolivia Chile Colombia Dom. Republic Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Venezuela Replacement or major reform 1994 1994 2005 1979 1991 2003 1994 1983 1998 1983 1985 1993 1982 1987 1995 1983 1992 1993 1983 1999 Freedom House 1 year before 2/3 2/3 1/1 2/3 3/4 4/4 3/3 2/2 3/3 4/5 5/6 4/5 4/3 5/6 4/5 5/4 3/3 6/5 1/2 2/3 Freedom House 1 year after 2/3 2/4 1/1 2/3 2/4 4/4 4/3 2/2 2/3 3/5 3/3 4/5 3/3 5/4 3/3 4/3 3/3 5/4 1/2 3/5 Freedom House 5 years after 2/3 1/3 -2/3 4/4 3/3 2/3 2/2 3/3 3/3 3/4 3/4 2/3 4/3 3/3 6/5 4/3 5/4 1/2 3/4 4. Constitutionalisation of Politics: Many Latin American constitutions are quite voluminous. They not only delineate political rights and the basic rules of the polity, but they may also provide the baselines for certain policy areas. Thus, a change of policies may require 19 a change of the constitution. This is especially the case in Brazil, but is also true of other countries (for example, Mexico and Colombia). In a comprehensive study, Couto and Arantes (2003; 2006; Arantes/Couto 2007) demonstrate that approximately 70 percent of the constitutional amendments during the governments of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–1998, 1999–2002) in Brazil concerned public policies. The reason for this policy of constitutional reform – which demands broader majorities in parliament (three-fifths) – instead of ordinary legislation is the constitutionalisation of public policies in the Brazilian constitution of 1988. The rationale for this feature of the Brazilian constitution was the decentralised nature of the constitutional reform process in 1987–1988, which facilitated the articulation of particularistic interests and regulations. Major changes in political orientation – because of political swings in parliament or a new political temperament – resulted in constitutional amendments, creating a specific modus operandi of the constitutional reform process in Brazil. Based on the Brazilian experience, Couto and Arantes (2003; 2006; Arantes/Couto 2007) make a distinction between the policy- and polity-oriented aspects of a constitution. The polity-oriented characteristics refer to the definitions of the state and nation, the basic individual rights, and the rules of political game. In a maximalist definition they also include material rights related to welfare and equality as well as to the corresponding state functions. In addition, the authors add two exclusionary criteria which should verify inclusion as a polity-related norm: the generality of the corresponding constitutional norms and their noncontroversial status. The last criterion refers to the question of whether these constitutional provisions have been part of the day-by-day political disputes. According to these criteria, out of 1,627 provisions (in 245 articles) in the 1988 Brazilian constitution, 30.5 percent are related to policies and 69.5 percent to the polity. Of the constitutional amendments, 68.8 percent were policy related and only 31.2 percent polity related; 60.8 percent of all amendments aggregated new provisions to the constitution, and of these amendments, 82.7 percent were policy related. Thus, during the government of F.H. Cardoso the volume of the constitutional text was augmented through the addition of 250 new policy-oriented provisions. In this way, President Cardoso constitutionalised even more the government agenda of future presidents. It is therefore no surprise that President Lula, Cardoso’s successor, has continued the practice of legislating by means of constitutional amendments and of governing by supercoalitions in order to bolster a three-fifths majority in Congress. 20 Future research should take a closer look at policy-related regulations in Latin American constitutions, especially in reference to the cases of Colombia and Mexico but also concerning other constitutions. Contrary to this article’s approach of excluding transitory regulations, an analysis of the policy content of constitutions should perhaps include the transitory dispositions because in some cases these transitory articles include policy instructions for future governments. 5. Power Politics: A constitution defines the basic rules of the political game. Sometimes political actors try to change these rules for their own benefit / advantage. This can certainly be the case with regard to the electoral rules. 20 Thus, in Latin America in the 1990s the articles that regulate /define the rules for presidential re-election have been reformed quite frequently. Traditionally, direct re-election has been proscribed. Since 1992, ten countries have reformed their constitutions with regard to the rules governing presidential re-election 21 and three have changed them twice (Colombia, Dominican Republic, Peru). In general, the reelection rules have become less restrictive, changing from prohibited to not immediate or immediate re-election. Sometimes the reforms have been passed for the direct benefit of the incumbent president. For instance, the entire Argentinian constitutional reform process in 1994 had at its core the re-election ambition of President Carlos Menem (1989–1999). In Peru, President Alberto Fujimori (1990–2000) disbanded Congress in an autogolpe (1992). The constitution that was promulgated afterwards endorsed his immediate re-election. 22 The 1998 constitutional overhaul in Venezuela authorised immediate re-election, and Hugo Chavez, notwithstanding his defeat in a referendum, is still battling for another constitutional reform that will allow permanent re-election. Two popular presidents, Fernando Henrique Cardoso in Brazil (1995–2002) and Álvaro Uribe in Colombia (2002–2010), secured their reelection after the reform of the constitution. Only the former president of the Dominican Republic, Hipólito Mejía (2000–2004), did not succeed with his re-election bid after he had reformed the constitution. However, his successor, Leonel Fernández, will probably take advantage of the reform and be re-elected. 20 A recent study lists more than 50 reforms to the electoral laws for the upper and lower houses in Latin America in the period 1978–2005 (Payne et al. 2007). Some reforms were part of a constitutional reform package.. 21 In Costa Rica non-immediate re-election was prohibited by referendum. The Constitutional Court restored non-immediate re-election in 2003, because it decided that the process of reforming the re-election rule was unconstitutional. 22 The 1993 constitution limited the presidency to two consecutive terms. The politically manipulated Peruvian electoral bodies permitted a third candidacy. After Fujimori won a highly contested and fraudulent election, he had to resign some months later after a political scandal involving the director of his secret service. 21 Table 4: Constitutional Change in Latin America: Re-election of Presidents Country Argentina Brazil Colombia Dominican Republic Ecuador Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Venezuela Year of reform 1994 1997 1991 2005 1994 2002 1996 1995 1994 1992 1993 2000 1998 Nature of reform not immediate to immediate not immediate to immediate not immediate to prohibited prohibited to immediate immediate to not immediate not immediate to immediate prohibited to not immediate immediate to not immediate not immediate: increasing the required interval from one to two presidential terms immediate to prohibited not immediate to immediate immediate to not immediate not immediate to immediate Source: Payne et al. (2007: 32). In a few cases, the procedures of a constitutional reform have been used to alter the power distribution by creating a new power center in the form of a constitutional assembly. By claiming a higher democratic legitimacy than parliament, the constitutional assembly could try to replace parliament. This was the master plan of Hugo Chavez in Venezuela in 1998/1999. The script has been copied more or less successfully by Enrique Correa in Ecuador (2007–2008) and Evo Morales in Bolivia (2006–2007). In Nicaragua in 2005 an oppositional majority tried to disempower the president by means of a constitutional reform. An institutional crisis was avoided through another constitutional reform, which postponed the original reform and suspended any constitutional reform until 2008. We can find empirical illustrations of all the aforementioned causes of constitutional reform. Moreover, the explanations are not mutually exclusive. In general, there will be a mix of motives for constitutional reform. In the future it would be useful to statistically assess and weight the relative importance of the different causes of constitutional reform. However, it will also be necessary to do more qualitative research with regard to the factors that provoke or facilitate constitutional reform. Perhaps it will be possible to identify certain reform patterns or country profiles. 22 5. Future Research Topics Future research on constitutional change in Latin America – including replacements as well as amendments – should focus on a differentiation of the database (and statistical analysis), more qualitative research on specific reform processes, and the identification of causal factors in order to obtain a more dynamic picture of the constitutional reform processes in Latin America. With respect to the databases, it will be necessary to differentiate between major and minor reforms (combining qualitative and quantitative criteria)23 , between reform topics (for example policy- and polity-related reforms, and also sub-categories), between different reform periods, and between reform processes in liberal and illiberal democracies / semidemocracies. There should be some qualitative research on selected constitutional reforms in specific countries in order to better capture the dynamics of constitutional reform processes and to identify more push and pull factors. Moreover, it will be necessary to take a closer look at the political constellation (minority/majority status of government, divided government, political discontent, demonstrations, etc.), additional institutional factors (for example, the role of constitutional courts), economic trends (growth rates, etc.), and social developments (protest movements, etc.) in the context of constitutional reforms. It is likely that it will be difficult to identify general trends to explain constitutional change in Latin America; it will be more plausible to identify certain time-bound or country-specific constitutional reform patterns. 23 It would be interesting to weight statistically the extent of constitutional reforms, as Lorenz (2004) has done for developed democracies. However, this would be quite complicated: There is great variation with regard to the scope of the reforms – from one article to a nearly complete overhaul of the constitution (with more than 30 articles, or in one case more than 100 articles, reformed without constitutional replacement). And sometimes a small number of reforms to the basic parameters of the political game (polity) can be more important than a higher number of policy-related constitutional reforms. 23 Annex 24 Table 1: Constitutional Reform in Latin America in the Twentieth Century Country Argentina Bolivia Brazil Chile Colombia Costa Rica Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Mexico Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Uruguay Venezuela Total Mean Source: Negretto (2006). Constitutions, 1900–2000 4 6 6 3 2 4 4 8 7 5 8 2 8 4 4 5 6 16 102 5.7 Average duration 36.75 20.00 18.20 55.70 57.00 32.25 28.25 12.90 16.30 24.20 13.25 71.00 13.40 24.00 32.50 26.60 28.30 6.30 28.70 25 Table 2: Constitutional Change in Latin America, 1978–2007 Country Argentina Bolivia Year of actual constitution 1853 Number of replacements since 1978 Year Articles reformed 1 1994 43 in process 2008 1 1 1 1 total: 4 1994 2002 2004 2005 29 16 14 1 total: 60 2 2 6** 5 6 2 3 4 7 4 4 3 3 3 5 3 total: 62 56 EMC* and 6 (1994) EMR** 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 3 10 9 9 11 7 50 17 20 14 11 35 35 6 14 4 total: 255 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 total: 10 1989 1991 1997 1999 2000 2001 2003 2005 2007 30 22 30 9 2 2 1 58 2 total: 154 1988 1 Chile Amendments partial reforms 1967 (1) Brazil Year 1980 1 1988 1980 26 Colombia 1991 1 Costa Rica 1 1 1 1 total: 4 1979 1981 1983 1986 68 3 1 6 total: 78 2 2 1 1 1 2 4 4 4 2 5 total: 28 (1991–2007) 1993 1995 1996 1997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2 3 2 1 1 2 8 9 57 5 5 total: 96 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 3 3 2 2 1 2 total: 23 (since 1978), 31 (1949– 1977) 1981 1982 1984 1987 1989 1991 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 1 1 1 2 4 1 1 1 2 2 6 4 2 2 6 3 total: 39 (since 1978), 46 (1949– 1977) 1 1 1994 2002 6 2 1991 1949 Dominican Republic 1966 Ecuador*** 1998 total: 2 1 (1) El Salvador total: 8 1 1983 58 1 1 1 total: 4 1994 1995 1997 4 10 13 total: 27 (85) 1 1 2 1 1991 1992 1994 1996 16 3 3 6 1998 in process 2008 1983 1 1983 27 Guatemala 1 6 total: 35 1 1993 34 1 1 1 2 2 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 1 1 1 4 2 2 total: 29 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1990 1991 1993 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 12 2 1 2 3 2 1 3 2 4 4 1 18 2 19 13 25 4 3 total: 121 3 1 3 3 3 5 2 4 6 1 2 4 7 3 1 2 1 10 3 1 2 2 5 5 4 9 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1985 1986 1987 1988 1990 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 3 1 3 5 19 10 2 10 22 1 12 8 33 29 1 23 3 20 3 5 3 3 8 9 5 25 1985 1982 1 Mexico 1999 2000 1985 1 Honduras 1 2 total: 8 1982 1917 total: 266 total: 92 Nicaragua 1987 1 1987 1 1995 65 28 Panama Paraguay Peru Uruguay 1 3 total: 5 2000 2005 19 8 total: 92 1 1 1 1 1 total: 5 1978 1983 1993 1994 2004 2 150 9 7 4 total: 172 --- --- --- 2 1 1 1 3 total: 8 (1993–2005) 1995 2000 2002 2004 2005 2 1 12 4 8 1 1 1 1 1989 1994 1996 2004 1972 1992 (no reform or amendments 1978–1991) 1 1992 1 1993 (no reform or amendments 1992–2007) 1993 no reforms or amendments (1979–1993) total: 27 1967 total: 4 Venezuela LA 1999 (no reforms / amendments 1961–1982) 1 11 1 1 4 1 total: 7 --- --- --- 1 1983 32 1999 *EMC – Emenda Constitucional; **EMR – Emenda Constitucional de Revisao; ***Ecuador enacted a new constitution in 1978. 29 Table 3: Political Regimes in Latin America, 1978–2007 Country Argentina Bolivia Brazil Chile Colombia Costa Rica Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Mexico Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Uruguay Venezuela Liberal / illiberal democracy Liberal / illiberal semi- Non-democracy / democracy repressive semidemocracy 1983–2001, 2003–2004 2002 1978–1982 (2005–2007) 1983–2004 1978–1982 (2005–2007) 1990–2004 1985–1989 1978–1984 (2005–2007) 1989–2004 1978–1988 (2005–2007) 1978–2004 (2005–2007) 1978–2004 (2005–2007) 1978–2004 (2005–2007) 1979–1995, 2001–2004 1996–1999 1978, 2000 (2005–2007) 1994–2004 1980, 1985–1993 1978–1979, 1981–1984 (2005–2007) 1996–2004 1986–1990 1978–1985, 1991–1995 (2005–2007) 1997–2004 1981–1996 1978–1980 (2005–2007) 2000–2004 1988–1999 1978–1987 (2005–2007) 1990–2004 1988 1978–1987, 1989 (2005–2007) 1994–2004 1984–1985, 1990–1993 1978–1983, 1986–1989 (2005–2007) 1993–2004 1990–1992 1978–1989 (2005–2007) 1980–1991, 2001–2004 1994–2000 1978–1979, 1992–1993 (2005–2007) 1985–2004 1978–1984 (2005–2007) 1978–1998 1999, 2002–2004 2000–2001 (2005–2007) Source: Smith / Ziegler (2008) and addendum D.N. (2006–2007) based on Freedom House 2006-2007. 30 Table 4: Instruments of Constitutional Reform in Latin America Country Argentina Bolivia 1967 Bolivia 2002 Bolivia 2004 Brazil Chile Colombia Costa Rica Dominican Republic Ecuador El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Mexico Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru Uruguay Venezuela 1961 Venezuela 1999 Vote of Congress (majority) x (2/3) x a (2/3) x a (2/3) x (2/3) x (3/5) x (3/5; 2/3) x (majority) x (2/3) x (2/3) d x (2/3) xa (2/3) e x (2/3) x (2/3) x (2/3) x a (60%; 2/3) xa (majority) x (majority) (2/3) x (majority) (2/3) x (2/5) x (majority) x (2/3) x (majority) x (2/3) x (majority) x (2/3) Constituent assembly Plebiscite Vote of state parliaments x x (x) c (x) b (x) b (x) b (x) c (x) b (x) b (x) f x x (x) c (x) b (x) c x (x) b x x x x x x x x (x) c a) two different legislatures have to approve the reform; b) constituent assembly or plebiscite not obligatory; c) constituent assembly only in the case of a total/general reform; d) in a common session of both houses of Congress as National Assembly; e) first vote simple majority, in the next legislature two-thirds majority; f) only in the case of reforms of the basic rights. Source: Political Database of the Americas. 31 Table 5: Constitutional Rigidity in Latin America, 1978–2007 Country Lijphart Argentina Bolivia 1967 Bolivia 2002 Bolivia 2004 Brazil Chile Colombia Costa Rica Scores Veto points major minor revised reform reform minor reform 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.5 3.0 3.0 <3.5> 2.0 2.0 3.0 2.0 2.5 1.0 1.0 3.0 3.0 <3.5> Dominican Republic Ecuador 1979 Ecuador 1996/98 El Salvador Guatemala Honduras Mexico Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru 1979 Peru 1993 Uruguay Venezuela 1961 Venezuela 1999 Latin America (mean) taking the lowest value most recent constitution Source: Political Database of the Americas. 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 4.0 2.0 <3.0> 1.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 3.0 4.0 2.0 1.0 2.0/3.0 2.0 1.0 2.0/3.0 2.0 3.0 1.0 2.0 <3.0> 3.0 3.0 2.6 2.5 3.5 3.5 <3.5> 2.0 3.5/2.5 2.0 2.5 <3.5> 3.5 Lorenz (modified) 2 4 5 4 <2> 2 3/4 2/3 4.0 9.0 (12.0) 10.0 (13.0) 9.0 (12.0) <4.0> 6.0 9.0 / 10.0 2.0 /3.0 1 <2> 3 2/3 2/3 2 2 1 3 1 <2> 2/3 3 4 2 /1 2/3 3 <4> 2 3.0 <4.0> 5.0 5.0 6.0 /7.0 3.5 (4.0) 4.0 3.0 7.0 3.0 <2.5 (4)> 2.0 / 3.0 3.0 <7.0> 4.0 2.0 / 3.0 2.0 /3.0/7.0 5.0 <9.0> 4.0 2.1 4.3 < > total replacement / reform / different options / procedures Argentina: Congress has to vote by a two-thirds majority on the necessity of a reform; afterwards a constituent assembly is elected. Bolivia: The original 1967 constitution provided only for partial reform. The reform (first the necessity of a reform and second the reform proposal) had to be approved by a two-thirds majority in each chamber in two independent legislatures. The 2002 reforms added a referendum on the reforms voted in Congress. The 2004 reforms included the possibility of total reform by a constitutional assembly. The modus of reform had to be approved by a two-thirds majority of Congress. Brazil: Majority of three-fifths in both houses. Chile: The reform proposal has to be approved by a two-thirds or three-fifths majority, contingent on the importance given to these topics by the authoritarian constitution makers in 1980 to preserving the stats quo. The president can veto the reform proposal or part of the reforms, but Congress can insist with a two-thirds majority. In this case the president has to promulgate the reform or call a referendum. 32 Colombia: There are three options: majority vote in both houses (with regard to certain topics the citizens can demand and initiate a referendum); majority vote in both houses to elect a constituent assembly; by initiative of the government or the citizens and a law approved by the majority of both houses with a subsequent referendum. Costa Rica: Two-thirds majority in two ordinary legislative period; total reform needs approval of a two-thirds majority of Congress to elect a constituent assembly. Dominican Republic: The necessity of reform is declared by a law (simple majority in both houses); then it requires approval by a two-thirds majority in a common session of both houses (with the participation of more than half of the members of each house). Ecuador: 1979: Two-thirds majority of members of parliament; referendum if a constitutional reform proposal from the president is rejected by Congress or if the president objects to a constitutional reform proposal approved by parliament. 1996: two-thirds of the members of parliament, but the president can veto or alter parts of the reform proposal. Parliament can overrule the presidential veto with a two-thirds majority. The president can call a referendum on the parts not approved or overruled by parliament. According to the 1998 reform, with the consent of the president and the majority of parliament, the reform proposal could be voted on in a referendum after parliament had approved it with a two-thirds majority. El Salvador: A reform proposal has to be approved by a majority of parliament and ratified by a two-thirds majority in the subsequent parliament. Guatemala: Articles referring to individual rights, two-thirds majority and constitutional assembly; other articles, two-thirds majority and referendum (consulta popular). Honduras: Two-thirds majority in two ordinary legislative periods. Mexico: Two-thirds of the present members of Congress and majority of the state assemblies. Nicaragua : A partial reform must be approved by 60 percent; the necessity of a total reform must be approved by a two-thirds majority. Afterwards, a constituent assembly will be elected. Panama: Absolute majority of the members of parliament in two successive legislatures. There will be a referendum if the text is modified in the second legislature. Paraguay: The constitution could only be removed 10 years after its promulgation (1992) and could only be amended three years after. Total reform or major reform: through a two-thirds absolute majority vote by its members, the two chambers of Congress may declare the need for constitutional reform and, afterwards, the election of a constituent assembly. Amendment: absolute majority in both chambers, afterwards referendum. Peru: 1979: absolute majority in both houses in the first period of two consecutive legislatures. 1993: absolute majority and approval by referendum or two-thirds majority in two legislative periods (legislaturas ordinarias sucesivas). Uruguay: There are four procedures of constitutional reform (including by popular initiative of 10 percent of the electorate). Each reform proposal has to be voted on in a referendum. Parliament can initiate a constitutional reform with a two-fifths majority in a common session of both houses, with a two-thirds majority in each chamber, or with a majority in a common session of both houses and a constituent assembly elected afterwards. Venezuela. In the 1961 constitution amendments had to be approved by an absolute majority in both houses of Congress as well as by two-thirds of the state assemblies. The necessity of a total reform had to be approved first by a two-thirds majority in a common session of both houses of Congress. Afterwards it had to be approved in an ordinary legislative procedure and voted on in a referendum. The 1999 constitution includes different forms of constitutional reforms: partial reforms must be approved by a two-thirds majority of Congress and a referendum (simple majority). The president or 15 percent of the electorate as well as Congress can initiate amendments of one or a few articles of the constitution as well as the election of a constituent assembly. The stipulations in the constitution with regard to these two options are quite vague. 33 Table 6: Length / regulation density of Latin American constitutions Country Argentina 1957 Argentina 1993 Bolivia 1967 Bolivia 1994 Bolivia 2005 Brazil 1988 Brazil 2005 Chile 1988 Chile 1989 Chile 2005 Colombia 1979 Colombia 1991 Colombia 2005 Costa Rica 1981 Costa Rica 2003 Dom. Rep 1966 Dom. Rep. 1994 Dom. Rep. 2002 Ecuador 1978 Ecuador 1984 Ecuador 1996 Ecuador 1997 Ecuador 1998 El Salvador 1983 El Salvador 2000 Guatemala 1985 Guatemala 1993 Honduras 1982 Honduras 2005 Mexico 1988 Mexico 2004 Nicaragua 1987 Nicaragua 1995 Nicaragua 2005 Panama 1983 Panama 1994 Panama 2004 Paraguay 1967 Paraguay 1992 Peru 1979 Peru 1993 Peru 2005 Uruguay 1967 Uruguay 2004 Venezuela 1961 Venezuela 1973 Venezuela 1981 Venezuela 1999 Mean (most recent date) Articles Words Index articles + words 110 129 235 235 233 a 245 251 b 119 117 c 126 d 7,349 11,328 14,989 16,525 18,223 39,531 49,141 21,439 21,425 24,371 1.8 2.4 3.8 4.0 4.1 6.4 7.4 3.3 3.3 3.7 380 379 e 34,819 41,024 7.3 7.9 177 115 120 120 15,544 10,955 11,954 11,957 3.0 2.2 2.4 2.4 144 181 181 284 249 273 280 280 375 372 f 136 136 195 195 195 311 318 g 318 g 231 291 307 206 206 332 332 252 254 263 350 247 12,917 16,055 17,171 26,584 19,771 20,822 24,195 25,799 22,576 24,616 2.7 3.4 3.5 5.5 4.5 4.8 5.2 5.4 6.0 6.2 44,625 10,079 16,278 16,983 21,925 23,158 23,257 13,405 24,464 18,362 16,692 17,725 25,200 26,932 16,833 17,029 17,667 34,489 25,438 5.8 2.9 3.6 3.6 5.3 5.5 5.5 2.6 5.4 4.9 3.7 3.8 5.8 6.0 4.2 4.2 4.4 6.9 5.0 a) BOL: two articles without content, therefore not included in the counting b) BRA: three articles (117, 171, 233) derogated, but number still included in text. Five new articles (103 A, 103 B, 111 A, 146 A, 149 A). c) CHI: two derogated articles (8, 118) without content d) CHI: one derogated article (118) without content; one subdivided, numbered 80 A to 80 I e) COL: two derogated articles (261, 265) without content; one new, numbered 263-A f) HON: six articles derogated, but numbers in still included constitution text g) PAN: two derogated articles (196, 197) without content 34 Bibliography: Arantes, Rogério Bastos / Couto, Cláudio Gonçalves, 2007. Shifting policies: the process of constituional amendment in Brazil, Paper prepared for delivery at the 2007 Meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, Montreal, September 5-8, 2007. Barros, Robert, 2002. Constitutionalism and Dictatorship, Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. Couto, Cláudio Gonçalves / Arantes, Rogério Bastos, 2006. Constituição, governo e democracia no Brasil, in: Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais Vol. 21, N° 61, 41-62 Couto, Cláudio Gonçalves / Arantes, Rogério Bastos, 2003. ¿Constitución o políticas públicas? Una evaluación de los años FHC, in: Vicente Palermo (ed.), Política brasileña contemporánea: de Collor a Lula en años de transformación, Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintuno Editores, xxx-xxx. Garzón Valdés, Ernesto, 2000. Constitución y Democracia em América Latina, in: Anuário de Derecho Constitucional Latinoamericano. Edición 2000. Buenos Aires: CIEDLA, 55-80 Inter-American Development Bank, 2005. The Politics of Policies. Economic and Social Progress in Latin America 2006 Report, IDB, Washinton D.C. Lijphart, Arend, 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Govenment Forms and Performance in ThirtySix Countries, New Haven: Yale University Press. Llanos, Mariana/ Nolte, Detlef, 2003. Bicameralism in the Americas: Around the Extremes of Symmetry and Incongruence, Journal of Legislative Studies 9.3, 2003: 54-86. Lösing, Norbert, 2001. Nomos. Die Verfassungsgerichtsbarkeit in Lateinamerika, Baden-Baden: Lorenz, Astrid, 2005. How to measure constitutional rigidity, in: Journal of Theoretical Politics 17 (3): 339-361. Lorenz, Astrid, 2004. Stabile Verfassungen? Konstitutionelle Reformen in Demokratien, in Zeitschrift für Parlamentsfragen 35 (3): 448-468. Lutz, Donald S., 1994. Toward a Theory of Constitutional Amendment, American Political Science Review, 8.2, 355-370. Navia, Patricio / Ríos-Figueroa, Julio, 2005. The Constituional Adudication Mosaic of Latin America, Comparative Political Studies 38.2, 189-217. Negretto, Gabriel, 2006. The Durability of Constitutions in Changing Environments: A Study on Constitutional Stability in Latin America, Paper prepared for delivery at APSA Meeting, Philadelphia, PA, August 31-September 3, 2006 Payne, Mark J./Zovatto, Daniel / Mateo Díaz, Mercedes et al., 2007. Democracies in Development. Politics and reform in Latin America, Washington D.C.: Inter-Amerucan Development Bank. 35 PNUD, 2004. La Democracia en América Latina. Hacia una democracia de ciudadanos y ciudadanas, Lima: PNUD PNUD - International IDEA, 2007. Informe Nacional sobre Desarrrollo Humano 2007. El estado de la opinion, La Paz: PNUD – International IDEA. Rasch, Bjorn Erik/Congleton, Roger D., 2006. Amendment Procedures and Constitutional Stability, in: Congleton, Roger D. / Swedenborg, Birgitta (eds.), Democratic Constitutional Design and Public Policy, Cambridge: MIT Press, 319-342. Smith, Peter H. / Ziegler, Melissa R., 2008. Liberal and Illiberal Democracy in Latin America, Latin American Politics and Society 50.1, 31-58.