Tax Reforms in EU Member States

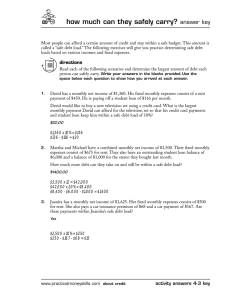

Anuncio