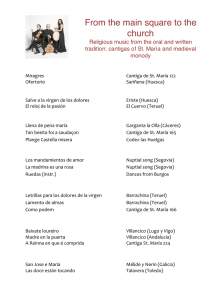

The Representation of Nature in

Anuncio