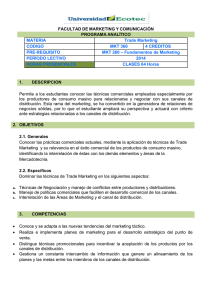

Factores determinantes de las Medidas No Arancelarias aplicadas

Anuncio