Plants known as té in Spain: An ethno-pharmaco

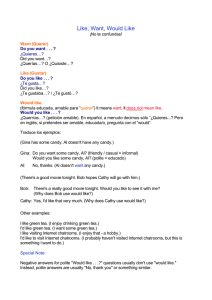

Anuncio