corrientes marinas autopistas del mar

Anuncio

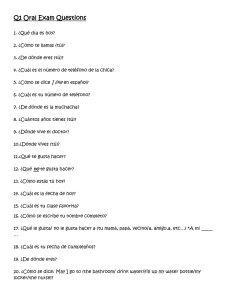

investigación CORRIENTES MARINAS AUTOPISTAS DEL MAR Un incesante tráfico discurre por las profundidades de los océanos. Son las corrientes marinas, termómetros vitales que regulan los climas y la biodiversidad del planeta. Marine Currents Highways of the Sea Incessant traffic flows through the depths of the oceans. They are the ocean currents, vital thermometers that regulate the planet’s climate and biodiversity. Texto: María Jesús Corrales Ilustración: Fernanda Algorta 32 33 investigación investigación LAS PRINCIPALES ARTERIAS DE LOS OCÉANOS THE MAIN ARTERIES OF THE OCEANS 14 y 27 DEL GOLFO Y KURO SHIVO 4, 5, 7, 13, 15, 21, 22, 26 y 28 ECUATORIALES GULF STREAM AND KURO SHIVO © Victor Ovies Arenas / Getty Images EQUATORIAL CURRENTS 18 17 1 34 “I learned a lot about myself on the trip; perhaps most importantly, that things are possible if you really want them.” When she was fourteen years old, between 2010 and 2011, Laura Dekker from Holland was the youngest person to have sailed alone on the world’s seas. Based on that experience, she could corroborate the importance of “keeping the currents in mind, especially if the electronics fail. It’s good to know which way the water flows. Nautical maps show it very well; we must keep in mind that the currents are constant, though sometimes they mix with the tide,” she says. They played tricks on her in the Indian Ocean and South Africa, which she remembers as “the worst moments of the trip”. Dekker’s experience demonstrates the importance of these water flows, since sailors use their synergies to cross the seas. However, their most important impact is on climate and biodiversity. “A current is like a bunch of whirlpools that flank the main course, forming meanders that sometimes close and break off as smaller rings and mix with the waters of the ocean.” It is thus that the Tenerife Energy Agency (Agencia Insular de la Energía Un temporal encrespa el oleaje frente a El Golfo, un pequeño pueblo de pescadores en la costa de Lanzarote. La corriente de las Canarias fluye hacia la costa. A storm curls the waves in front of El Golfo, a small fishing village on the coast of Lanzarote. The Canary current flows towards the coast. 16 29 2 “Aprendí mucho sobre mí misma en el viaje. Quizá lo más importante es que las cosas son posibles si realmente las deseas”. Cuando tenía catorce años de edad, entre 2010 y 2011, la holandesa Laura Dekker fue la persona más joven en navegar sola por los mares del mundo. Gracias a esa experiencia, pudo corroborar la importancia de “tener en mente las corrientes, sobre todo si la electrónica falla. Es muy bueno saber en qué dirección viene el agua. Los mapas náuticos lo muestran muy bien; hay que tener en cuenta que las corrientes son constantes aunque a veces se mezclan con las de marea”, indica. Le jugaron malas pasadas en el Índico y Sudáfrica, que recuerda como “los peores momentos del viaje”. La experiencia de Dekker evidencia la importancia de estos flujos de agua, pues los navegantes aprovechan sus sinergias para cruzar los mares. Pero lo más importante es cómo inciden en el clima y en la biodiversidad. “Una corriente se parece a un manojo de remolinos que flanquean un curso central, formando meandros que a veces se cierran y separan como anillos menores y se mezclan con las aguas del océano”. Así describe una masa oceánica el informe sobre corrientes de la Agencia Insular de la Energía de Tenerife. La corriente del Golfo transporta agua cálida de los trópicos del Atlántico al noroeste de Europa. Al llegar a su destino, el agua calienta las masas de aire superiores, que luego se desplazan al interior y provocan que el invierno sea templado en Europa, teoría que se halla en revisión. En el Pacífico, la corriente de Kuro Shivo es similar. The Gulf Stream carries warm water from the Atlantic tropics to northwest Europe. Upon arriving at its destination, the water heats up the air mass above it, which then moves inland and causes the winters in Europe to become milder, a theory that is under review. In the Pacific, the Kuro Shivo current is similar. Los vientos alisios contribuyen a formar las grandes corrientes Ecuatoriales. En la cuenca occidental de los océanos una cierta cantidad de agua se acumula en las proximidades del ecuador debido a la fuerza centrífuga generada por la rotación. El agua desplazada desde el otro hemisferio forma las contracorrientes Ecuatoriales. The trade winds contribute to the formation of the major Equatorial currents. In the Western ocean basin, a certain amount of water is accumulated in the vicinity of the Equator due to the centrifugal force generated by rotation. The water displaced from the other hemisphere forms the Equatorial counter currents. 14 3 4 OCÉANO ATLÁNTICO 15 OCÉANO PACÍFICO 31 5 22 30 13 7 10 6 OCÉANO PACÍFICO 28 27 23 21 OCÉANO ÍNDICO 24 26 12 19 20 11 8 25 9 6 HUMBOLDT HUMBOLDT La aridez que provocan las aguas frías de esta corriente afectan a las costas centrales y septentrionales de Chile y Perú. Su velocidad es de 28 kilómetros por día de sur a norte, desde la parte central de las costas chilenas hasta el ecuador terrestre. The dryness caused by the cold waters of this current affects the central and northern coasts of Chile and Peru. Its speed is 28 kilometres per day south to north, from the central part of the Chilean coast to inland Equator. 1 DE ALASKA 2 PACÍFICO NORTE 3 DE CALIFORNIA 4 ECUATORIAL DEL PACÍFICO NORTE 5 CONTRACORRIENTES ECUATORIALES 6 DE HUMBOLDT O DEL PERÚ 7 ECUATORIAL DEL PACÍFICO SUR 8 CABO DE HORNOS 9 ANTÁRTICA 10 BRASILEÑA 11 ATLÁNTICA DEL SUR 12 DE BENGUELA 13 ECUATORIAL DEL ATLÁNTICO 14 DEL GOLFO 15 ECUATORIAL DEL ATLÁNTICO NORTE 16 DEL ATLÁNTICO NORTE 17 DEL LABRADOR 18 DE GROENLANDIA 19 DE LAS AGUJAS 20 AUSTRALIANA DEL NORTE 21 ECUATORIAL DEL SUR 22 ECUATORIAL DEL NORTE 23 DEL MONZÓN 24 BENGALA 25 AUSTRALIANA DEL ESTE 26 ECUATORIAL DEL PACÍFICO SUR 27 KURO SHIVO 28 ECUATORIAL DEL PACÍFICO NORTE 29 OYA SHIVO 30 DE GUINEA 31 DE LAS CANARIAS 35 investigación 17 investigación millones de m3/s Caudal de la circulación profunda, 20 veces el de los ríos de todo el mundo. La corriente Antártica tarda entre100 y1.000 años en llegar al ecuador. 10% © Barcroft Media via Getty Images del agua del océano se desplaza en las corrientes superficiales. El resto, en aguas profundas. Las corrientes termohalinas discurren a 6.000 metros de Tenerife) describes an oceanic body of water in its report on currents. Remote sensing permits the collection of increasingly more data on these highways of the sea. In Europe, since 2012, the MyOcean project collects data from 2,400 tide gauges and buoys for biological research, as well as aid to navigation, port infrastructure and the detection of contaminant offenses. Underneath the seemingly calm surface of the ocean, there are superficial and deep “highways” that transport the heat received from the Sun all over the globe. In addition, they vary a lot based on temperature, density, salinity and the direction of their flow. Wind, the continent walls and the Earth’s rotation influence surface currents, which move in clockwise circles in the northern hemisphere and the opposite in the southern hemisphere, as stated by the Ministry of Culture’s Biosphere project. The trade winds, which “pushed” Columbus to the Caribbean, move water westward allowing colder waters from below to surface. This occurs, for exam- ple, in the Canary Islands. In turn, in the Arctic, a cold and very saline body of water is generated. It sinks and slowly heads south. At the Equator, it is pushed to the surface by even colder water from the Antarctic, which heads north from the South Pole through the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans. All this happens when the sea comes into contact with the air; however, in the deep, pelagic “tunnels” redistribute the heat and salt of the seas. These are the thermohaline currents. Scientists and conservationists are very concerned about the impact of freshwater input from melting polar caps on these currents. The coordinator of the WWF’s latest study on the threat that climate change poses to the oceans, Mauricio Galvez, said “thermohaline circulation has slowed in the northeast Atlantic due to climate change”. He adds that “other currents are also sensitive to global warming. Water outcrops produce an exchange of nutrients and oxygen, and they are essential for conserving marine biodiversity. In recent years, de profundidad. 4 grados centígrados. Temperatura máxima de las corrientes frías. 17 million m3/s. Deep circulation flow, 20 times that of all the rivers in the world. The Antarctic current takes between 100 and 1,000 years to reach the Equator. 10% of ocean water moves in surface currents. The rest, in deep water. The thermohaline currents flow at a depth of 6,000 metres. 4 degrees Celsius. Maximum temperature of the cold currents. 36 Y la teledetección permite recabar cada vez más datos sobre estas autopistas del mar. En Europa, el proyecto MyOcean recopila desde 2012 datos de 2.400 mareógrafos y boyas para investigaciones biológicas, de ayuda a la navegación, a la infraestructura portuaria y a la detección de infracciones contaminantes. Porque bajo la alfombra uniforme que aparenta ser el océano hay unas ‘carreteras’ superficiales y otras profundas que transportan el calor que reciben del Sol por todo el globo. Y son muy distintas en temperatura, densidad, salinidad y en la dirección en que circulan. El viento, la pared que imponen los continentes y la rotación terrestre influyen en las corrientes superficiales, que se mueven en círculos en el sentido de las agujas del reloj en el hemisferio norte y al contrario en el hemisferio sur, como indica el proyecto Biosfera del Ministerio de Cultura. Los vientos alisios que “empujaron” a Colón hacia el Caribe desplazan el agua hacia el oeste permitiendo que afloren las aguas más frías que corren por debajo. Esto ocurre, por ejemplo, en las islas Canarias. A su vez, en el Ártico se genera una masa de agua fría y muy salina que se hunde y se dirige, lenta, al sur. Pasado el Ecuador sube a la superficie, empujada por otra aún más fría, la antártica, que navega rumbo al norte desde el polo Sur por el Atlántico, el Índico y el Pacífico. Si todo esto sucede al contacto del mar con el aire, en el fondo “túneles” pelágicos redistribuyen el calor y la sal de los mares. Son las corrientes termohalinas. Y los científicos y conservacionistas están muy preocupados por cómo el aporte de agua dulce del deshielo polar afecta a estas corrientes. El coordinador del último estudio de la organización WWF sobre la amenaza del cambio climático en los océanos, Mauricio Gálvez, asegura que “la corriente termohalina se ha atenuado en el Atlántico noreste por el cambio climático”. Y añade que “otras también son sensibles al calentamiento global. Los afloramientos provo- Morsas sobre un bloque de hielo en el Ártico canadiense, donde se origina una corriente fría y salina. Walruses on a block of ice in the Canadian Arctic, where a cold saline stream originates. UN NIÑO DEMASIADO TRAVIESO A VERY NAUGHTY CHILD El Niño es un fenómeno causado por la rotación terrestre que desplaza las mareas del hemisferio norte al sur entre los trópicos. Cambia la temperatura del Pacífico Este y altera casi todos los patrones de circulación de las corrientes. Sucede cada tres u ocho años. El Niño is a phenomenon caused by the Earth’s rotation, which moves the Northern Hemisphere’s tides south between the tropics. It changes the temperature of the East Pacific and alters nearly all the currents’ patterns of movement. It happens every three to eight years. 37 investigación Los remolinos de agua indican los movimientos de las corrientes que entran y salen del Mar Mediterráneo por el Estrecho de Gribraltar. The whirlpools suggest the movement of the currents entering and leaving the Mediterranean Sea through the Strait of Gibraltar. DEL ESTRECHO A LAS CANARIAS FROM THE STRAIT TO THE CANARY ISLANDS El Estrecho de Gibraltar es un buen ejemplo de un cruce de corrientes. La atlántica entra caliente por la superficie, mientras sale la mediterránea, profunda, fría y densa. Esta corriente compensa el agua y la salinidad que el Mare Nostrum pierde por evaporación al ser un mar casi cerrado. A su vez, en Canarias el agua del Atlántico fluye hacia la costa, aflora desde el fondo y vuelve al océano. El fenómeno equilibra el mar profundo con las costas del Atlántico nororiental, en tanto incide en el clima de las Islas y en sus recursos marinos. The Strait of Gibraltar is a good example of a cross-current. The Atlantic current comes in warm on the surface, while the Mediterranean exits deep, cold and dense. This current compensates the water and salinity that the Mare Nostrum loses through evaporation, given that this sea is almost closed off. In turn, in the Canary Islands, Atlantic water flows towards the coast, it emerges from the deep, and returns to the ocean. The phenomenon balances the deep sea with the north-east Atlantic coasts; thus, it affects the climate of the islands and their marine resources. can intercambio de nutrientes y oxígeno y son claves para la biodiversidad marina. En años recientes, varios sistemas de surgencia se han atenuado con el calentamiento de sus aguas”. Gálvez insiste en que el cambio climático afecta además a “eventos extremos como ciclones y trombas, cada vez más comunes e intensos. Esto tiene consecuencias sobre la distribución, abundancia, ciclos reproductivos y migraciones de plantas y animales marinos”. Y recuerda que “ciertas especies se han distribuido más hacia los polos, impactando en otras de las que dependemos, porque los organismos marinos pueden responder más rápido al cambio climático que los terrestres”. Dice Laura Dekker que si se aleja del mar empieza a echarlo de menos. Si el equilibrio de las corrientes marinas se resquebrajase, la joven marina no sería la única en añorar lo que el mar significa para la vida. ■ 38 several upwelling systems have been diminished with warming of the waters”. Gálvez insists that climate change also affects “extreme events such as cyclones and hurricanes, which are becoming more common and intense. This has an impact on the distribution, abundance, reproductive cycles and migrations of marine plants and animals”. And he reminds us that “some species have been advancing towards the poles, affecting other species that we depend upon, because marine organisms can respond faster to climate change than ones living on dry land”. Laura Dekker says that if she is away from the sea, she begins to miss it. If the balance of marine currents were undermined, the young sailor would not be the only one who would miss the significance of the sea for fostering life. ■