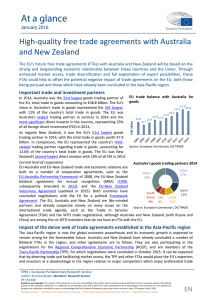

The Impact of Financial Services in EU Free Trade and Association

Anuncio