Training leave. Policies and practice in Europe - Cedefop

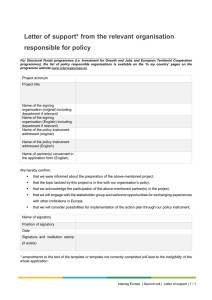

Anuncio