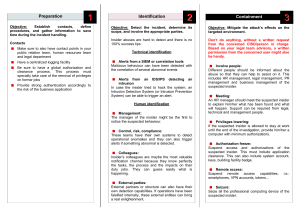

Behavioral Risk Indicators of Malicious Insider Theft of

Anuncio