rvm40201.pdf

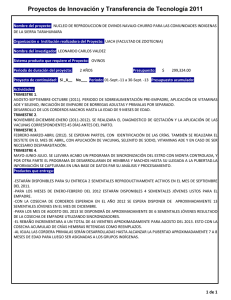

Anuncio