Geography Education Divide: University vs. Pre-University

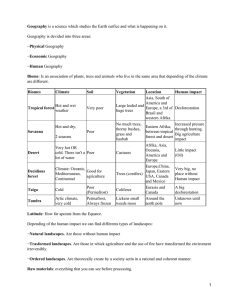

Anuncio

T R A N 2 5 2 Operator: Wang Jingjing Dispatch: 16.02.07 PE: Sally Moore Journal Name Manuscript No. Proofreader: Liang Lifen No. of Pages: 4 Copy-editor: Boundary Crossings Blackwell Publishing Ltd Geography without borders O F Noel Castree*, Duncan Fuller** and David Lambert† *Geography, School of Environment and Development, Manchester University, Manchester M13 9PL email: [email protected] **Geography, School of Applied Sciences, University of Northumbria, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 8ST †The Geographical Association, Sheffield S1 4BF D PR divide between university and pre-university geography. This divide, to be sure, is unevenly developed and in some countries scarcely exists. But in Britain, and more particularly England and Wales (where the three of us live and work and where geography remains enormously visible at the levels of both teaching and research), the university/pre-university schism is very stark indeed. What is the exact nature of the divide to which we refer? And why has it become a problem – one that should concern far more geographers than it apparently does? There was a time where university and preuniversity geography were closely connected in the British system. For instance, as recently as the mid1980s, university geographers played a central role in determining the old O and A level syllabi (both content and assessment). But over the last 20 years pre-university geography has lost significant points of connection with post-18 geography. Ironically, one of the last attempts of research-active geographers to write for geography teachers – the two Horizons volumes of 1989 (Gregory and Walford 1989; Clark et al. 1989) – occurred at a time when such cross-over activities became ever less likely to happen. Similarly, the A level magazine Geography Review – established during the mid1980s at Oxford University – found it harder to attract writers from research universities within a decade of its creation. This detachment between pre- and post-18 geography has a number of causes and dimensions. First, the several Research Assessment Exercises since the mid-1980s have focused many university geographers’ minds on publishing higher-level research outputs. Second, attempts to get university geographers’ apparently ‘haphazard’ teaching U N C O R R EC TE Until relatively recently, at least, one of us would have been on the receiving end of this message, rather than its (co)author. However, people change – often as a consequence of being gifted an unexpected opportunity to reflect (or being forced to!) upon their modus operandi. We want to convey a simple message: namely that British geography is beset by at least one quite fundamental problem. And something must be done – for all our sakes. Let us explain. Debates about the ‘state of geography’ are as old as the discipline itself. In metaphorical terms, the idea of a border (‘hard’ or ‘soft’) continues to animate these discussions. It appears in writings about geography’s ‘internal’ problems (if problems they really are) – such as the human–physical ‘divide’ or the sub-disciplinary ‘fragmentation’ of the two ‘halves’ of the discipline. It is also to be found at work in ruminations on geography’s ‘external’ challenges – such as its apparent inability to influence the policy world ‘out there’ or its supposed failure to stop other disciplines treading on its ‘turf’. Whilst talk of borders may well be inappropriate and unhelpful (the notion of ‘networks’, for example, creates a very different sense of geography’s internal configuration and its wider connectivities), such talk might continue to serve a very useful purpose because it obliges us to reflect on whether real (as opposed to imagined) divisions are currently constitutive of what geography’s all about; and it obliges us to ask whether such divisions are a ‘problem’ (for they aren’t necessarily). There is one aspect of professional geography today that is barely discussed in print and where, in our view, the metaphor of a border (and a ‘hard’ if not consciously policed one at that) is wholly appropriate. We are talking about the very real O revised manuscript received 15 January 2007 Trans Inst Br Geogr NS 31 000–0000 2007 ISSN 0020 -2754 © 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007 2 Border Crossing D PR O O F some would say, for this has challenged the traditional notion of a ‘curriculum’ in many departments). In sum, university and pre-university geography in this country are like distant relations: there is a family connection but it is fairly weak. Though no one is actively prohibiting closer ties between the two ‘worlds’ of geography, the institutional and personal constraints are such that we could think of them as distinct domains of thought and practice. Most university geographers in Britain know virtually nothing about pre-18 geography and yet many readily and regularly bemoan its apparent lack of contemporary focus and irrelevance; likewise, teachers, teacher-trainers, set-text writers and syllabus-setters in pre-18 geography scarcely have the opportunity or the time to get a handle on university geography or to engage with university geographers. There are, of course, exceptions – but by definition they prove the rule. Worse, they are often stigmatized. It is a measure of how haughty some university geographers have become that colleagues who involve themselves in, say, the Geographical Association (GA) or GEES (the national subject centre for Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences) are regarded – if coffee room and corridor chat is to be believed – simply as people who can’t ‘cut it’ as researchers. Obviously, one view is that this state of affairs is not all problematic. There are, perhaps, two main reasons why some might assure themselves that there is no real need for the current situation to change; no real need to make the ‘border’ easier to cross. First, around 20 000 students are currently studying for geography degrees, diplomas and certificates in numerous universities and colleges. So pre-18 British geography is doing just fine because – so one argument goes – it’s producing an unprecedented number of post-18 geography candidates. Second, it arguably doesn’t matter that pre-18 geography is, today, as often as not a far cry from degree-level geography, because once at university and college students have three or more years to be (re)educated into a different kind of geography – the kind that we academics value and (hopefully) the wider society too. Would that things were so simple. In fact, the estrangement between university and pre-university geography has a range of highly negative consequences. Intellectually it is, to say the least, careless to allow ‘school geography’ to be shaped and governed without awareness or concern from the academy. At worst, professors of geography U N C O R R EC TE practice in order led many of them to focus-in on their syllabi and pedagogic practices (if only because they were obliged to). The Quality Assurance Agency and its inspectors helped to ‘professionalize’ teaching in British universities (for better or for worse). In so doing it arguably contributed, in tandem with the RAE, to reduced traffic in ideas between pre- and post-18 geography teaching. But this reduction in traffic had several other causes too. Following the 1988 Education Reform Act the school curriculum was codified for the first time and a statutory ‘school geography’ came into being. This was monitored and administered by agencies such as the schools’ inspectorate (Ofsted) and the Qualifications and Curriculum Agency (QCA). School geography was characterized by the government of the day as ‘content rich’ and even at the time looked strangely set in aspic. Its details were, perhaps inevitably, laid out in a phenomenally successful textbook series (Waugh and Bushell 1991) in a ‘winner takes all’ market. The significance of this is that investment in textbooks tends to set the tone for many years. In practice, a single author’s interpretation of the newly codified school geography was able to withstand successive QCA reforms (largely designed to loosen the rigidity of the original curriculum) in a large proportion of secondary schools in England. Meanwhile, the attention of school teachers has been drawn to a massive government investment since 1997 in generic pedagogic skills development (though the so-called ‘national strategies’). Strategy consultants have literally replaced subject advisers in local education authorities, driven by the intense pressure of performance league tables. Thus, in many schools today, the professional focus of leadership teams is on ‘standards’ (meaning ‘performance’ measured by test results) and it is now very difficult indeed for geography teachers to pursue professional development through the subject – even when opportunities to do so exist. There is now deep confusion in the pre-university system about the role of subjects. Increasing numbers of school leaders talk about the ‘skills curriculum’ and ‘learning to learn’, demoting subjects to tired lists of statutory ‘content’ that needs to be ‘delivered’. Geography, possibly more than most subjects, suffers greatly when stuck with such impoverished language, in a kind of educational doldrums. By contrast, even in the aftermath of the QAA era, university geography has continued to diversify and innovate teaching-wise (too much Trans Inst Br Geogr NS 31 000–000 2007 ISSN 0020 -2754 © 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007 Border Crossing 3 D PR O O F content via a discipline of the same name. But in countries where geography is no longer (or never was) central as a primary and high school subject, university geography is (or has become) either small or merged with cognate subjects. Australia is currently a prime example here, while in the early 1980s a fair number of important US geography departments were closed down. But we have already had a taster of possible things to come here in Britain (albeit not caused by a decline in GCSE and A level geography enrolments): the well-known closure of the Lampeter Geography programme a decade or so ago, since when some other small geography departments have fallen by the wayside. There are several possible ways forward to address the difficulties we have outlined here. A prominent initiative is the Action Plan for Geography (http://www.geographyteachingtoday.org.uk), a two-year £2m programme, jointly and equally led by the Geographical Association and the Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers). Through its geography ambassadors scheme, professional support and curriculum development projects, the Action Plan seeks to ‘provide a clear vision of geography’ and significantly to enhance the attraction of geography to school students and their parents. It has set out to boost the confidence of school teachers of geography by promoting creative activity across the whole community of geography. From the higher education perspective, there are actions that individuals can take (and, of course, many already do) that range in required effort, scale of engagement and resources needed (time included). But all can contribute, somehow, somewhere. A few ideas: join the GA – a key, active, passionate and professional geographical body – to remain in touch with school geography debates and issues which feed interest in the geographical world amongst our communities of budding geographers; attend the GA conference (http:// www.geography.org.uk/conference) every two or three years for the same purpose; and of course, where possible, accept or seek-out invitations to speak at teacher or school events. More recently the GA has led a range of funded curriculum development projects and it has proved highly valuable to engage academics on the various sounding boards and steering groups. The ‘Valuing Places’, ‘Where Will I Live’ and, currently, ‘Building Sustainable Communities’ curriculum projects (http://www. geography.org.uk/projects) all have frameworks and U N C O R R EC TE claiming their work is ‘post-disciplinary’ and refusing to dirty their hands with ‘what makes it geography’ are risking the elimination of the subject at school level. Already a new subject has been invented called ‘citizenship’. Setting aside whether citizenship is a subject with a disciplinary hinterland like geography or history (it is not), it is already possible to study it to GCSE (the examination taken at 16 years old). Citizenship is a statutory requirement until 16 years, and there may soon be a 16–18 A level examination course. Make no mistake, unless geography can confidently claim its disciplinary focus and value it will suffer a consequential loss of young people wanting to study it beyond 14 years – and, indeed, head teachers wanting to go on even offering it as an option. There are schools already where geography is no longer available at GCSE. More generally, since 2000 geography has experienced a loss of nearly 20 per cent of candidates at GCSE, part of a long-term downward trend (to 213 469 candidates in 2006). At A level the pattern is more erratic, but here too the last six years have shown a decline in popularity of about the same proportions (32 522 candidates in 2006). It is hard to imagine that a continued collapse of geography examination candidates at school will not have a knock-on effect on applications to higher education courses. Some university and college departments may feel that they do not need to worry too much about this in the short term. Others may feel it would be reckless to proceed on the basis of current reputation, in a marketplace where the wider perception of geography may become increasingly less favourable. But, surely, ‘They can’t do away with geography?!!’ Whatever next!! Ironically, such a doomsday scenario does not necessarily mean ‘less geography’ for school students. Young people need to experience an education process that exposes them to thinking productively about a range of global issues such as migration, intercultural understanding, climate change, the impact of economic globalization, and so on. Make no mistake again: if geography continues to wither in school settings (and ultimately this trend is repeated in higher education settings too), these issues will still be covered – only not by geographers. So we come to the heart of the matter: what would be lacking if this came to be? And do we (or others) care? Naturally, most geographers might argue that ‘geography matters’ in a double sense: that is, in terms of both content and the institutional delivery of that Trans Inst Br Geogr NS 31 000–000 2007 ISSN 0020 -2754 © 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007 4 Border Crossing D PR O O F (pejoratively) as ‘the teaching-and-learning’ types were to use their continued energy and enthusiasm to break down the prejudice behind this label. At the very least, all so-called ‘research’ departments in British geography should organize in-house events that update staff on the current nature of (and issues facing) GSCE and A level Geography. The arguments we’ve put forward do not, we hope, make us as unlikely a writing trio as we might otherwise seem to be. One of us is based in an international ‘research university’; one of us in an ostensibly ‘teaching university’ engaged in many out-reach activities in its city-region and beyond; and one of us is head of the Geographical Association, a body commonly seen as being about pre-university teaching and ‘teachers’. These differences do not, and never should, confine us to different worlds of geographical practice, nor insulate us from the pressing need to play our own role in averting a potential curriculum crisis – indeed, a crisis of geographical literacy in the wider society. It’s time to recognize some of the shared agendas and interests that bind together otherwise disparate members of the geographical community. If not, we will only have ourselves to blame. References Clark M, Gregory K and Gurnell A eds 1989 Horizons in physical geography Macmillan, London Gregory D and Walford R eds 1989 Horizons in human geography Macmillan, London Waugh D and Bushell T 1991 Key geography Stanley Thorne, London U N C O R R EC TE content that have benefited from interacting directly with university geography. Get in touch and network with fellow local geographers, of whatever ilk. To aide this process, and in order to broaden the scope of such ‘cross-border’ involvement, the GA is now set on a course to re-form its academic journal Geography. With a new editorial collective (that spans higher education and schools), it will remain a journal in which academics will be invited to write – but specifically for a wider professional audience of teachers and education professionals. From a researcher’s perspective this is in the interests of creating a journal that will provide an overt opportunity for knowledge transfer – and hopefully contribute to the subject’s dynamism across the academic communities of school and higher education. These initiatives are important, but very much led (or likely to be led) from the pre-18 ‘side’ of the border to which we’ve been referring. What is still needed is more vigorous and widespread involvement from geographers in and throughout the university system. This will not be easy, and it is very much up to the Royal Geographical SocietyInstitute of British Geographers, heads of university geography departments and the GEES subject centre to devise strategies to facilitate this process. It will be necessary to take risks – for instance, to incorporate the need for ‘external liaisons’ and cross-border fertilization into workload spreadsheets, seminar programmes or appraisal discussions for example. It would also help if those university and college geographers often tagged Trans Inst Br Geogr NS 31 000–000 2007 ISSN 0020 -2754 © 2007 The Authors. Journal compilation © Royal Geographical Society (with The Institute of British Geographers) 2007 MARKED PROOF Please correct and return this set Please use the proof correction marks shown below for all alterations and corrections. If you wish to return your proof by fax you should ensure that all amendments are written clearly in dark ink and are made well within the page margins. Instruction to printer Leave unchanged Insert in text the matter indicated in the margin Delete Textual mark under matter to remain New matter followed by or through single character, rule or underline or through all characters to be deleted Substitute character or substitute part of one or more word(s) Change to italics Change to capitals Change to small capitals Change to bold type Change to bold italic Change to lower case Change italic to upright type under matter to be changed under matter to be changed under matter to be changed under matter to be changed under matter to be changed Encircle matter to be changed (As above) Change bold to non-bold type (As above) Insert ‘superior’ character Marginal mark through letter or through characters through character or where required or new character or new characters or under character e.g. Insert ‘inferior’ character (As above) Insert full stop Insert comma (As above) Insert single quotation marks (As above) Insert double quotation marks (As above) over character e.g. (As above) or or (As above) Transpose Close up linking Insert or substitute space between characters or words through character or where required Reduce space between characters or words and/or or or Insert hyphen Start new paragraph No new paragraph or characters between characters or words affected and/or