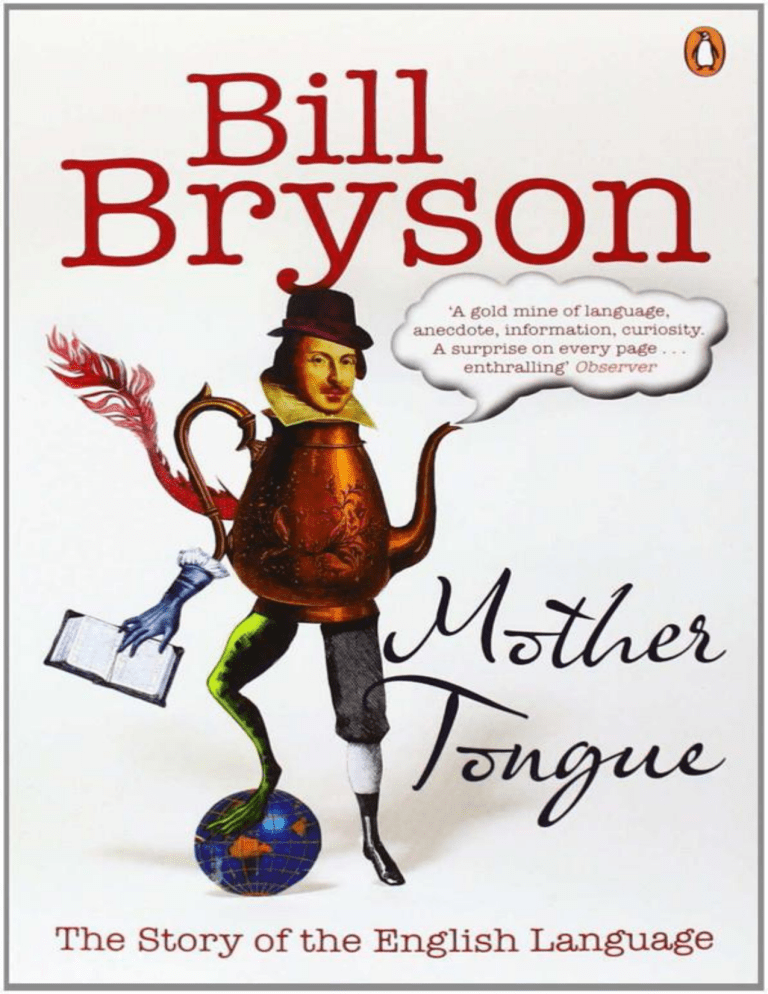

2. Mother Tongue The Story of the English Language (Bill Bryson) (z-lib.org)

Anuncio