El Provencio (Cuenca, Spain) the research possibilities of a new complete stratigraphic and archaeological sequence from Lower to Middle Paleolithic Domínguez-Solera et al 2019

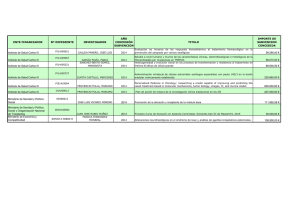

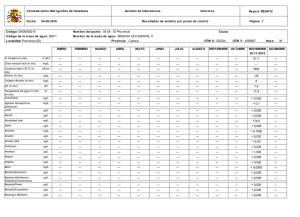

Anuncio

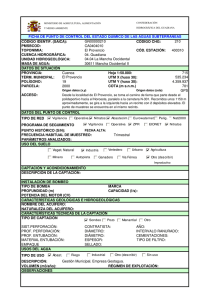

EL PROVENCIO (CUENCA, SPAIN): THE RESEARCH POSSIBILITIES OF A NEW COMPLETE STRATIGRAPHIC AND ARCHAEOLOGICAL SEQUENCE FROM LOWER TO MIDDLE PALEOLITHIC S.D. Domínguez-Solera (1) , D. Moreno, (2) , C. Pérez (3) , G.I. López (2) , M. Muñoz (1) (1) ARES Arqueología y Patrimonio Cultural, C/San Vicente 2, 16001, Cuenca (España) [email protected] (2) Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana, Paseo Sierra Atapuerca, 3 09002, Burgos (España) [email protected] [email protected] (3) Instituto Geológico y Minero de España, Calle Calera, 1 28760 Tres Cantos, Madrid (España) [email protected] Resumen (El Provencio (Cuenca, España): Las posibilidades para la investigación de una nueva secuencia estratigráfica y arqueológica desde el Paleolítico Inferior al Medio): Esta breve comunicación contiene los resultados preliminares del proyecto de investigación arqueológica sobre el Paleolítico Inferior y Medio en el término municipal de El Provencio (Cuenca, España). Durante los primeros 6 años de proyecto, se ha definido un hasta ahora desconocido complejo arqueológico con una gran concentración de restos de industria lítica de Modos 1, 2 y 3, asociados a secuencias fluviales y lacustres de gran extensión. Se presentan aquí las primeras edades obtenidas por dos métodos de datación complementarios: Resonancia Paramagnética Electrónica (ESR por sus siglas en inglés) y Luminiscencia Óptica (OSL por sus siglas en inglés). Las fechas de 41 ka y 800 ka corresponden a los niveles 2 y 3 de la secuencia estratigráfica respectivamente. El potencial arqueológico contenido en este enclave sugiere una ocupación humana ininterrumpida e intensa de esta región durante 800 ka. Palabras clave: Paleolítico Inferior; Paleolítico Medio; OSL; ESR; industria lítica. Key words: Lower Paleolithic; Middle Paleolithic; OSL dating; ESR dating; lithic industry. INTRODUCTION AND LOCATION New results from the Lower to Middle Paleolithic archaeological site of El Provencio Complex, located in the municipality that bears the same name in the south of the Province of Cuenca (central Spain) are summarized herein. The stratigraphic sequence is part of La Mancha plateau and is composed by an extensive succession of horizontally emplaced fluviolacustrine units rich in gravels and sands pertaining to the Záncara River deposits, one of the main tributaries of the Guadiana River. Three decades ago, during the industrial exploitation of some sand quarries, Mammuthus meridionalis and Bison dental remains were found and studied by several experts (Pérez-González et al., 1990). Preliminary analysis of lithic artifacts may appear to belong to Modes 1, 2 and 3 which in turn have been reinforced by the first Electron Spin Resonance (ESR) and Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) ages ever obtained for this region. ARCHAEOLOGICAL BACKGROUND The research project in El Provencio began in 2013 and belongs to a bigger research program about the human origins which encompasses all three regions pertaining to the Province of Cuenca: Alcarria, Mancha and Sierra (Domínguez-Solera & Martín, 2015; Domínguez-Solera, 2018a). This specific research program started with systematic surveying of old quarries which in turn, allowed to select new excavation sites such as El Pinar de la Vega, El Pinarico, Los Marines… forming El Provencio Complex. Between 2013 and 2015 surface findings unveiled a rich quartzite and flint lithic industry (retouched and unretouched tools, cores and debris of various types) as well as some faunal remains. During the subsequent excavations campaigns (2015-2017) at El Pinar de la Vega, the lithic artifacts Fig. 1: Stratigraphic profiles from the excavation in El Pinar de la Vega (above) and from the quarry profile in El Pinarico (below). S.D. Domínguez-Solera. were found in stratigraphic position (DomínguezSolera & Muñoz, 2015; Domínguez-Solera, 2018b). Archaeological surveys and excavations were focused on the sand- and gravel-rich layers found throughout El Provencio Complex, which seemed to be the most associated with the Paleolithic riches in the region. RESULTS Geochronology Samples were collected using sampling strategies recommended for trapped-charged dating techniques (Moreno et al, 2017). Dosimetry measurements were obtained both in the lab and in-situ using highprecision Germanium detectors and portable Gamma spectrometry, respectively (Table 1). To establish the chronology of El Provencio Complex, the first two ESR and OSL samples were collected in 2015 at El Pinarico and El Pinar de la Vega quarries profiles, respectively (Figure 1). ESR sample EPO15-06 was collected in the sterile Layer 3 of El Pinarico profile whereas OSL sample EPP15-05 was retrieved from sub-level 2E at El Pinar de la Vega cut (Figure 2). STRATIGRAPHY The general stratigraphy of the El Provencio Complex is composed of 3 main layers with an overall thickness of up to 5 m and deployed in an extension of at least 4.5 km. None of the strata seem to be affected tectonically. The bottommost layer is characterized by massive sands and is sterile of archaeological remains. Layer 2 shows inter-bedding of sands and gravel and is sub-divided into several sub-levels (e.g., A to I in El Pinar de la Vega profile; Figure 1). The main concentration of lithic industry of Modes 1 to 3 is found in this layer. The uppermost layer, Layer 1, is clay-rich and contains Mode 4 lithic industry, as well as Neolithic-Calcolithic ceramics and microliths. This horizontal stratigraphic scheme is repeated symmetrically and consistent throughout all the quarries and profiles studied in El Provencio Complex. Sample preparation, irradiation, bleaching, measurements and analyses were carried out at the ESR and Luminescence laboratories at the CENIEH (Burgos, Spain) (Table 1). ESR dating was performed on pure quartz separates (100-200 μm) using the Multiple Centre approach (Toyoda et al., 2000). ESR signals of Aluminum (Al) and Titanium (Ti) centers were systematically measured on 14 aliquots by triplicates over different days. The ESR ages obtained for Layer 3 are 826 ± 48 ka (Al-center) and 846 ± 43 ka (Ti-center) (Table 2). Sample DĮ Dȕ DȖ Dcos Dint Dose Rate EPP1505 - 150 ± 10 150 ± 10 150 ± 10 - 450 ± 20 EPO1506 11 ± 2 532 ± 7 380 ± 14 157 ± 16 50 ± 30 1131 ± 37 Table 2. Dosimetric data from ESR and OSL samples (DĮ: alpha; Dȕ: beta; DȖ: gamma; Dcos: cosmic; Dint: internal doses). Values in μGy/a. Sample DE Age EPP1505 18.6 ± 0.6 41 ± 2.2 EPO1506 Al-center 934 ± 78 826 ± 48 Ti-center 957 ± 37 846 ± 43 Table 2. ESR and OSL dose equivalent (DE) values (in Gy) and corresponding ages (in ka). OSL dating was determined on pure quartz separates (90-125 μm) using the Single-Aliquot Regenerative-Dose (SAR) protocol (Murray & Wintle, 2000) on 24 multiple-grain aliquots (2 mm diameter). A Central Age Model (CAM) age of 41 ± 2.2 ka was obtained for layer 2 (Table 2). Both samples were taken from different quarries, but we had corroborated, previously, that they were part of the same geologic and stratigraphic sequence. Archaeology Thousands of lithic artifacts were gathered and described during the surface surveys in several locations from El Provencio Complex including El Pinar de la Vega, El Pinarico, Los Marines, La Mezquita or El Tostado. Fig. 2. Photographs of ESR and OSL samples on the respective quarry profiles from El Pinarico and El Pinar de la Vega.Photos: D. Moreno. artifacts were made in quartzite and the rest in flint. All the quartzite artifacts are easily classified as Mode 1 industry and the flint artifacts as Modes 2 and 3. Including a fragmented biface. From the original 247 processed artifacts, 81 were found on the surface during initial surveying, hence out of stratigraphic position. Whereas, the rest 166 artifacts found in stratigraphic position while excavating -with the exception of three retouched quartzite Mode 1 artifacts- are classified as Mode 3. These show typical features of Levallois reduction (Table 3). Preliminary traceology analyses have already begun. Nonetheless, it has been difficult to find traces of use on the edges of even the best preserved tools. DISCUSSION The abundance of artifacts detected in El Provencio Complex may imply a continuous and intense human occupation between the Lower and Middle Paleolithic in this central region of the Iberian Peninsula. This is a different point of view as other interpretations suggested by different authors where the abundance of Paleolithic artifacts and populations is concentrated near the coast (e.g., De la Torre, 2017). The features observed in surface and stratigraphy artifacts suggest a classification in the three earliest modes of tool-making: Modes 1, 2 and 3. The hominins that produced such artifacts may be chronologically associated to Homo antecessor and Homo heidelbergensis populations that were already present in Atapuerca (Carbonell et al., 2008). A preferential usage of the local materials to make the three modes of industry is argued and also a continuity of the same operational chain in Mode 3 expanded across 150.000 years. Hence, El Provencio Complex may bear the potential of further investigations concerning social learning and imitations as already proven effective analytical methods in other important Paleolithic archaeological sites in Spain (e.g., Baena et al., 2008; Blasco et al., 2013). Fig. 3. Examples of lithic Modes 1 and 3 from the areas of El Pinarico, El Pinar de la Vega and Los Marines. S. D. Domínguez-Solera. The ESR age of ~800 ka obtained for Layer 3 gives a terminum ante quem for the beginning of Mode 1 in El Provencio Complex. The youngest sub-level, Layer 2E, dated by OSL gave an age of 41 ka. But there are five more levels with Mode 3 industry above (layers 2A, 2B, 2C, 2DI and 2DII). This could be associated with Neanderthal timing of Southern Europe. The limit of Mousterian or Neanderthal history in South Europe is being established 30.00024.000 years ago (Garralda, 2005; Finlayson et al., 2008). To further prove the existence of Neanderthals in this region at this younger period, more archaeological campaigns are envisioned. The identified Mode 1 artifacts (both from excavation and surveys) are all retouched and cortical flakes made from flint or quartzite, as well as cores with simple reduction strategy (no more than 6 extractions; Figure 3). Also, there are several examples of Mode 2 bifacial handaxes and largeformat tools, always in flint material. The largest lithic assemblage, hence the most studied thus far at El Provencio Complex, pertains to Mode 3 industry (Figure 3): most of them show a stereotypical Levallois centripetal technique but also the Levallois parallel method. In both cases, local flint little nodules (5-10 centimeters long) were the raw material. CONCLUSIONS Over the last 800 ka, human hunter and gatherer bands of different species came recurrently on an uninterrupted way (independently of the different stages of climate change), to the old Záncara margins attracted by the different animal and vegetable resources that there were concentrated During the two excavation campaigns carried out in El Pinar de la Vega a total of 255 different artifacts have already been obtained, most of them from secure stratigraphic origin. 8 are flint cores without traces of reduction, while the other 247 show traces of knapping. In terms of raw material, 14 of those 247 LITHIC (FIINT) FROM EXCAVATION IN EL PINAR DE LA VEGA (EL PROVENCIO) Cores Flakes/blades/points Debris TOTAL 1 4 1 6 1 5 8 14 4 3 15 22 15 6 8 29 17 12 24 53 1 1 4 6 1 4 13 18 5 5 5 15 46 40 78 163 5,75 5 9,75 20,37 28% 24% 48% 100% CORES FROM EXCAVATION IN EL PINAR DE LA VEGA (EL PROVENCIO) Levallois Levallois little dimensions Levall. cor. for Other blades Layer Centripetal Parallel NI Centripetal Parallel NI 2 A-B 1 2C 1 2DI 1 1 1 1 2D2 3 3 7 1 1 2E 2 7 4 4 1 2F 1 2G 1 2H 2 2 1 DISCRIMINATION TOOLS/DEBRIS FROM EXCAVATION PIECES IN EL PINAR DE LA VEGA (EL PRV.) Layer Retouched tools Without functional retouch 2 A-B 3 2 2C 6 7 2DI 4 14 2 D II 7 7 2E 12 14 2F 1 4 2G 9 7 2H 5 5 TOTAL 47 60 AVERAGE 5.87 7,5 Layer 2 A-B 2C 2DI 2 D II 2E 2F 2G 2H TOTAL AVERAGE % Table 3. Inventory tables of excavation lithic pieces from El Pinar de la Vega (El Provencio). península Ibérica. (López, coord.) Istmo, Akal, Madrid: 121-222. Domínguez-Solera, S. D. (2018a). El Paleolítico Inferior y Medio en la Provincia de Cuenca: balance del proyecto, nuevas fechas absolutas y perspectivas. Cuando empezábamos a ser nosotr@s: Curso sobre el Paleolítico Inferior y Medio a nivel mundial (DomínguezSolera, coordinador). Diputación de Cuenca, Cuenca: 4576. Domínguez-Solera, S. D. (2018b). El Paleolítico Inferior y Medio en El Provencio (Cuenca): trabajos de 2013 a 2017. Cuando empezábamos a ser nosotr@s: Curso sobre el Paleolítico Inferior y Medio a nivel mundial (Domínguez-Solera, coordinador). Diputación de Cuenca, Cuenca: 77-99. Domínguez-Solera, S. D. and Martín Lerma, I. (2015). Hallazgo de industria lítica del modo 1 en la Alcarria Conquense: El Yacimiento de “El Pino” (Carrascosa del Campo, Cuenca). AnMurcia, 31: 109-116 Domínguez-Solera, S. D. and Muñoz, M. (2015). El Paleolítico en El Provencio. Nuestro Entorno. Nuestra Historia, 1: 18-22. Finlayson, C. et al. (2008). Gorham’s Cave, Gibraltar – The persistence of a Neanderthal Population. Quaternary International, 181: 64-71. Garralda, M. D. (2005). Los Neandertales en la Península Ibérica. Munibe, 57: 289-314. Moreno, D.; Richard, M.; Bahain, J.J.; Duval, M.; Falguères, C.; Tissoux, H. and Voinchet, P. (2017). ESR dating of sedimentary quartz grains: some basic guidelines to ensure optimal sampling conditions. Quaternaire, 28 (2), 161-166 Murray, A.S. and Wintle, A.G. (2000). Luminescence dating of quartz using an improved single-aliquot regenerativedose protocol. Radiation Measurements 32, 57-73. Pérez-González, A.; Mazo, A. V. and Aguirre, E. (1990). Las faunas pleistocenas de Fuensanta del Júcar y El Provencio y su significado en la evolución del Cuaternario de la Llanura Manchega. Boletín Geológico y Minero, Vol. 101, número 3: 56-70. Toyoda, S.; Voinchet, P. ; Falguères, C. ; Dolo, J.M. and Laurent, M. (2000): Bleaching of ESR signals by the sunlight : a laboratory experiment for establishing the ESR dating of sediments. Applied Radiation and Isotopes 52 (5), 1357-1362. here. These groups would use local raw materials (flint and quartzite), reducing, processing and elaborating tools as well as discarding them in situ. Even though much geological work is yet to be done, the geochronological data obtained so far corroborates the archaeological findings. Future work is not only envisioned towards Zooarchaeology (the few faunal remains that were found for now are all surface and very eroded materials) but also to obtain a better chronostratigraphical control of El Provencio Complex. The potential of El Provencio Complex is still unknown and could provide much information related to the last 800 ka in the central region of the Iberian Peninsula. Acknowledgements: The authors thank the Council of El Provencio, especially its Culture Councilor (D. José Manuel Triguero Valladolid) for supporting and financing this project (authorized by the JCCM administration). We also thank the local inhabitants and all those that help us during all these past years. S.D. Domínguez would also like to thank ARES ARQUEOLOGÍA staff. REFERENCES Baena, J. et al. (2008). Tecnología musteriense en la región madrileña: un discurso enfrentado entre valles y páramos de la Meseta sur. Treballs d’Arqueologia, 14: 249-278. Blasco, R.; Rosell, J.; Domínguez-Rodrigo, M. et al. (2013). Learning by Heart: Cultural Patterns in the Faunal Processing Sequence during the Middle Pleistocene. PlosOne, 8 (2): 1-20. Carbonell, E.; Bermúdez de Castro, J.M.; Parés, J.M.; Pérez-González, A. et al. (2008). The first hominin of Europe. Nature, Vol. 452/27 (march): 465-470. De la Torre, I. (2017). El Paleolítico en España: más de un millón de años en la historia de la evolución humana. Historia de España I. Prehistoria. La Prehistoria en la