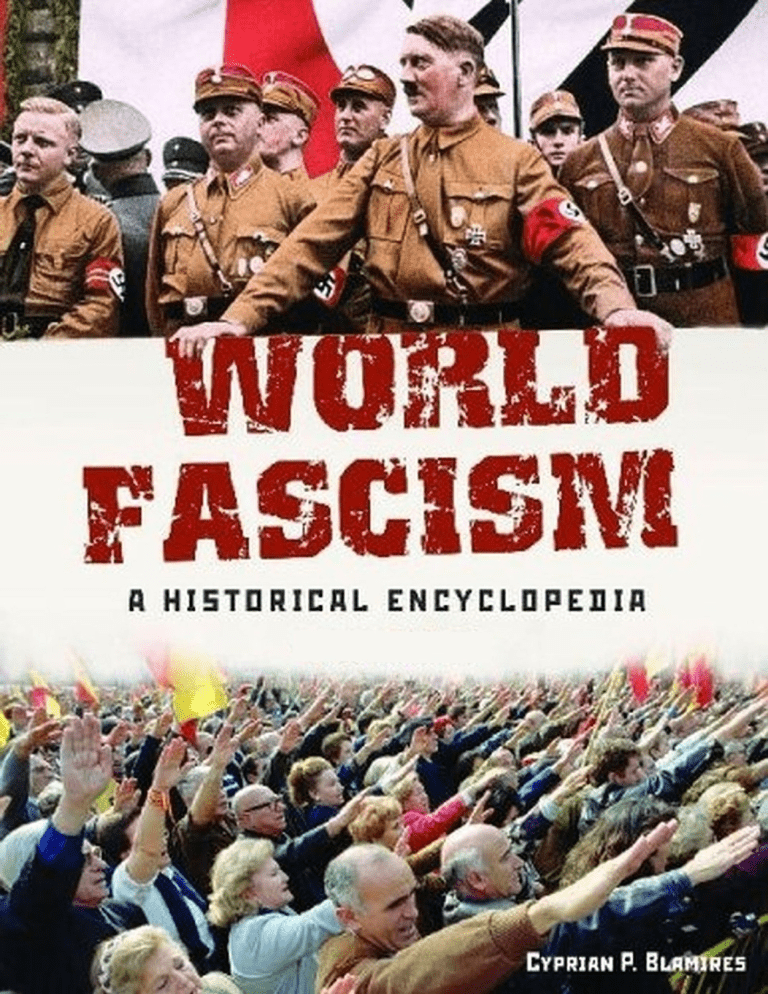

Cyprian Blamires - World Fascism A Historical Encyclopedia-ABC-CLIO (2006)

Anuncio