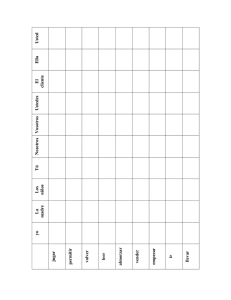

Safety of Women in the context of Urban Streets and Spaces -Ameeshi Shrivastava “Historically, public spaces have been the domain of men. Women are relatively new entrants and have been staking their claim to male-dominated public spaces only in the last few hundred years or so. Men have built cities to their convenience, so when women begin to navigate them, they have to find or make space for themselves.” (EPW Engage, 2019). Women are believed to be dispensable when compared to their male equivalents. There are a lot of systemic irregularities that contribute to and are evidence of this very notion1. A lack of female representation in positions of power and high-paying jobs. 2. Exploitation of labour rights and non-acceptance of equal pay for equal work in corporate and global markets. 3. Sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse against women. All these issues have originated from deep-rooted systemic and institutional patriarchy and misogyny. Men have established a hierarchy of genders in which they have placed themselves at the very top, thus internalising a sense of entitlement over most things including women. Approaching this from an architectural vantage point, not even public spaces and urban streets are excused from this very entitlement and privilege. Women get noticed and have to endure unwanted attention and flak for things that no one would raise an eyebrow for had it been a man. They experience this on a daily basis as it has been normalised by society and is not a crucial subject matter in popular architectural discourses. It, therefore, escapes the public eye and continues to persist. “1 in 3 women globally” (Devastatingly Pervasive: 1 in 3 Women Globally Experience Violence, 2020) and 4 out of 5 women in India have been subjected to some or the other form of street harassment such as being stalked, wolf-whistling, insults, objectification, groping and in the most heinous (but not entirely rare) crime of sexual assault and rape. What makes these streets unsafe? What are the elements that these urban spaces manifest that contribute to these unsolicited situations? The characteristics of a space can define the sense of safety an individual experiences when they are using this space. One such example is women not preferring to use spaces that are dark and lack adequate lighting. These particular spaces can become more inviting and relatively safer just by introducing a few lampposts and street lights. The parameters that dictate the safety of a public street or an urban space are- 1. Location 2. Entry/Access 3. Line of Sight with respect to surroundings 4. Vegetation 5. Footfall 6. Lighting 7. Neighbourhood 8. Presence of paths/ jogging tracks Source- Daily Express The location of a public space plays an important role in dictating its usability and inclusivity. Women avoid secluded spaces and spaces that appear deserted, isolated and off the beaten track. This can be linked with the simple concept of ‘eyes on the street’ coined by none other than author Jane Jacobs. Women prefer to visit spaces that are more tended to and are not a far-reaching detour from their regular and familiar surroundings. The footfall, visual connectivity, lighting, etc, all trace back to the concept of ‘eyes on the street’. The more the people engage with a space visually, the safer it gets. The entry and access points of a particular park or urban setting are also a deciding factor in whether a space can be perceived as ‘safe’. Multiple unhindered exit/access points make a public space safer for women as it aids easy movement and circulation. The level at which a particular space has been built determines its line of sight and visibility with respect to its surroundings. One such example is the Sabarmati Riverfront Project in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The lower promenade of the riverfront has a level difference of over 12m as compared to the upper promenade. People prefer to use the lower promenade as it is shaded and acts as a respite from the harsh sun. The lower promenade however is not used by women as much as it should be because of the visual disconnect from the surroundings. Source- https://sabarmatiriverfront.com Trees and shrubs provide shade and create nodal points where people can gather. Bigger trees on the periphery might also obstruct visual connectivity and therefore become counterproductive to the cause. Peripheral paths and jogging tracks are also productive agents to aid safety and transparency. It is also important for parks and streets to be centred around spaces that are a subset of bigger functions such as museums, offices, stalls, markets, etc. This not only improves footfall but also becomes a day-to-day commute point for people going to work or setting up shops or going to the market. The park could provide a spine or an axis that connects people to these spaces so it opens up to the neighbourhood and can act as an irresistible circulatory space. Source- https://www.knocksense.com Presence of adequate lighting and street-lights can make a space usable and safe for women after dark. Simple provisions of floodlights and lamps make an individual feel safer and makes the surroundings less dense and more transparent. “Crime was reduced by an average of 21 per cent in areas with improved street lighting compared to areas without.” (College of Policing UK, 2015). Streetlights are a simple and efficient tool to curb crime and give a space more character and introduce people to a sense of being ‘seen’ thus preventing them from carrying out antisocial activities In conclusion, the solution to making public spaces actually ‘public’ are simple urban design and architectural interventions that can change the entire aura of the space for the better. The simple way to come to a solution would be to identify the elements breeding in these spaces that are making a negative impact on the space and trying to solve these problems by not only an active approach but also a passive approach of including these in architectural discussions and discourses about our cities and public spaces.