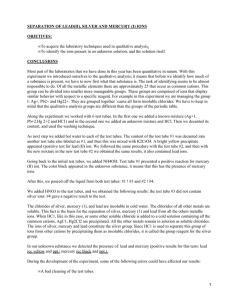

2009 - Kate L Crump - Mercuryinducedreproductiveimpairmentinfishretrieved 2018-09-02

Anuncio