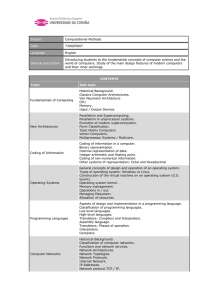

Summarization Exercises in E-Interpreting Training Yinghui Li School of English and Education/Bilingual Cognition and Development Lab, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies Center for Linguistics and Applied Linguistics, Baiyun Avenue North 2#, Baiyun District, 510420, Guangzhou, China (86)020-36207201 [email protected] ABSTRACT summarization; beginner; intermediate Summarization is widely used as an exercise both in traditional interpreting training and in distance or e-interpreting training to promote trainees’ efficiency in comprehension and recall of the source language information. So far, however, how student interpreters’ performance in summarization exercises relates to their interpreting performance remains unclear, let alone how the relationship may differ at different interpreting training stages. The current study thus invited 62 beginner student interpreters (Group 1) and 19 intermediate student interpreters (Group 2), examining and comparing how they performed in a task of consecutive interpreting from L2 (in this case English) to L1 (in this case Chinese) and how they performed in a post-interpreting summarization task. With quantitative analyses three major findings were obtained: (1) Group 2 had significantly better performance in interpreting than Group 1, while the two groups were not significantly different in their performance in summarization; (2) Either group’s summarization performance was significantly and positively correlated with their overall score in interpreting and with the target language grammaticality and appropriateness (one of the two interpreting sub-scores) as well; however, a significant correlation between summarization performance and information accuracy and completeness (the other interpreting sub-score) was only found in Group 1 but not in Group 2; (3) Group 1’s summarization performance significantly explained more than 20% variance in either the overall interpreting performance or the sub-score information accuracy and completeness, and either group’s summarization performance significantly explained no less than 20% variance in the target language grammaticality and appropriateness. Pedagogical implications are discussed. 1. INTRODUCTION Emerging information technologies have played an increasingly important role in the language service industry and the concerned education and training. Interpreting training, traditionally performed purely by humans, is now unexceptionally updated and revolutionized as computer-assisted interpreting training (CAIT) technology is employed by more and more interpreting trainers and trainees. CAIT technology facilitates interpreting training mainly with (1) digital interpreting laboratories equipped with state-of-art technology, (2) interpreting websites providing interactive virtual training environment, (3) terminology management systems, (4) application of learning management systems such as M oodle in interpreting training, and (5) corpora of transcribed input and output texts from real-life interpreting (aligned with audio-visual recordings) and various types of online exercises designed on the basis of these interpreting corpora [6,7,11,13]. In terms of the exercise adopted in interpreting training, summarization is the one frequently used both in traditional and distance or e-interpreting training (see a review in [9]). A popular type of summarization exercises is summarizing the source language (SL) input immediately after interpreting (named “post interpreting summarization”). Due to a lack of empirical research on this type of summarization, however, we do not understand yet how performance in this summarization is related to interpreting performance or how this exercise may help improve student interpreters’ interpreting performance. The present study is thus intended to explore the relationship between student interpreters’ post-interpreting summarization performance and interpreting performance. In doing so, the present study also scrutinizes potential difference in the relationship at different stages of interpreting training. Post-interpreting summarization as an exercise is usually used in training programmes of consecutive interpreting (CI) (where the speech is divided into segments by pauses made by the speech-maker and the interpreter renders what the speech-maker have said in the latest segment when the speechmaker pauses or finishes speaking), given that this interpreting mode features summarization and recall of information just as summarization exercises do. The present study hence focuses on CI rather than any other interpreting mode. CCS Concepts • Applied computing ➝ Distance learning • Applied computing ➝ E-learning Keywords interpreting training; student interpreter; interpreting performance; Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than the author(s) must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from [email protected]. ICDEL 2019, May 24–27, 2019, Shanghai, China © 2019 Copyright is held by the owner/author(s). Publication rights licensed to ACM. ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-6265-8/19/05…$15.00 2. RESEARCH BACKGROUND Though summarization is a type of exercise widely used in interpreting training [9,16], empirical research is scarce on the relationship between interpreting and this exercise. To examine the relationship between interpreting and recall of information (which shares critical cognitive processes with summarization of DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3338147.3338156 88 information), a previous study [5] compared student interpreters’ recall of information (short-stories and digits) in several different recall conditions. In the task of short-story recall, the student interpreters recalled stories in two conditions (i.e., ① after listening to the story to be recalled and ② after simultaneous interpreting in which the story to be recalled was the SL input). In the task of digit recall, the student interpreters recalled digits in four conditions, including ① recalling after listening to digits, ② recalling after shadowing digits (i.e., repeating digits out loud immediately after listening to them), ③ recalling after listening to digits with simultaneous articulatory suppression (i.e., listening to digits while uttering irrelevant syllables), and ④ recalling after simultaneously translating digits. as it is called in the field of interpreting). The present research aims at answering two major research questions: (1) How do student interpreters at different stages of interpreting training perform in interpreting and in post-interpreting summarization? (2) At different stages of interpreting training, how is postinterpreting summarization performance related to interpreting performance? 3. RESEARCH DESIGN 3.1 Participants Two groups of participants (Group 1, Group 2) were recruited on a voluntary basis. Group 1 consisted of 62 undergraduate students who majored in English in a national key foreign studies university and who were at the same time student interpreters at the end of a one-year interpreting training programme. Group 2 were composed of 19 postgraduate students enrolled in an intensive interpreting programme at the same university . When the two groups took the test, Group 1 had received 85 hours’ interpreting training on average and Group 2, who all had experience in real-life interpreting, had been trained in interpreting for 300 hours on average. Therefore, Group 1 was taken as beginner student interpreters and Group 2 was considered as intermediate student interpreters. Both groups of student interpreters, who had been English-as-a-foreign-language learners and users for at least ten years in China before they were recruited in the aforementioned undergraduate or postgraduate interpreting training programme, were cons idered unbalanced Chinese-English bilinguals with intermediate-high English proficiency. After comparing the performance in recalling short stories and the performance in recalling digits within group and between different recalling conditions, the study found that the student interpreters’ performance in recalling the story after simultaneous interpreting (SI) was not as good as their performance after only listening to the story. Besides, their performance in recalling digits after SI was not as good as their performance in the other three recalling conditions (i.e., after listening to digits, after shadowing digits, and after listening to digits with articulatory suppression). These findings seemed to indicate that interpreting may negatively affect one’s efficiency in recalling the SL information (either short stories or digits). In despite of this previous study, more empirical research is still warranted on the relationship between interpreting and summarization of the SL information out of three major reasons. First, owing to the scarcity in the related empirical research, the aforementioned potential negative relation found in this previous study still calls for further examination. Second, as this previous study only examined student interpreters at an advanced stage of interpreting training, research on student interpreters at the other stages of interpreting training is still needed. Third, given that interpreters in SI need to render the SL information into the target language (TL) as quickly as possible when the speech-maker speaks continuously, the interpreters who are mainly trained in and practice SI are found to have an advantage in updating information in their working memory system [14,15]. Such an advantage, on the other hand, may reduce their efficiency in storing and recalling the SL information and thus may become a disadvantage in information recall/summarization when they are compared with the interpreters who are mainly trained in and practice CI, where interpreters primarily recall the SL information in the latest speech segment as efficiently as possible before being able to render it into the TL. Therefore, the relationship between CI and recall/summarization of information may not be identical as the relationship between SI and recall/summarization of information found in this previous study. 3.2 Materials and Procedure Materials. The present study adapted a CI test from a speech that lasts for eight minutes and mainly promotes laptops for children. The original speech was made by a male speech-maker at a rate of 143 words per minute on average. Given that the participants were unbalanced Chinese-English bilinguals, the current study divided the speech into segments, each of which comprised two to three sentences. The length of each segment was proven appropriate for the present participants based on (1) results of a pilot study enrolling 20 participants from the population identical to Group 1’s and 3 participants from the population identical to Group 2’s, (2) judgments on how difficult the CI test was made by five interpreting instructors who had rich experience in instructing interpreting and who instructed at the same university as the participants, and (3) results of a questionnaire about the appropriateness of the CI test materials finished by the participants. A more detailed introduction to how this CI test was developed could be found in [2]. Procedure of CI test. Both groups finished the CI test in a digital laboratory for interpreting training. In the test, they listened to segments one by one and when each segment ends, they were given a cue to start interpreting. According to the results of a pilot study, the spell allowed for rendering each segment was 1.5 times the spell of the segment itself. When the interpreting time was up, participants heard another cue and after a brief interval, participants heard a new segment. During the test, participants were allowed to take notes and refer to the notes. To fill the aforementioned research gap , the present study mainly investigates the relationship between performance in postinterpreting summarization and CI performance. Besides, the current study aims at exploring potential difference in the aforementioned relationship at different stages of interpreting training, and it thus examines and compares the performance in the two aforementioned tasks between two groups of student interpreters who are currently at two different stages of interpreting training. To avoid potential weaknesses due to a small sample size, the current study collects data from more than 15 participants at each training stage. In accordance with student interpreters’ interpreting training curricula, the present study focuses on English-to-Chinese CI (i.e., L2-to-L1 CI or B-to-A CI Procedure of post-interpreting summarization. Once participants finished the CI test, they were required to write a summary in 150 to 200 words (in Chinese) about the SL input in no more than a quarter of an hour. Scoring of interpreting performance. Two interpreting instructors (who also worked as professional interpreters with 5 years’ 89 found between Group 1’s summarization performance and their two interpreting sub-scores, including Information and TL expressions (r = .60, p = .000 < .01; r = .52, p = .000 < .01). These results indicate that the beginner student interpreters who could comprehend and recall the SL information more efficiently tended to interpret better (either in the sense of the overall performance or in the two specific aspects of interpreting performance), and vice versa. interpreting experience on average) listened to recordings of all the 81 participants’ interpreting output and, based on the same scoring criteria, the instructors independently rated the participants’ CI performance. According to the criteria, which are generally accepted in CI training programmes, a participant's total score (100%) is composed of two proportions: (1) information accuracy and completeness (“Information” henceforth), taking up 67%, and (2) the TL grammaticality and appropriateness (“TL expressions” henceforth), which holds 33%. Each participant’s final score in interpreting was the average of the scores given by the two raters (inter-rater coefficient r = .95) Group 2’s summarization performance was also found positively and significantly correlated with Overall Score (r = .47, p = .043 < .05). A significant and positive correlation was also found between their summarization performance and TL expressions (r = .53, p = .019 < .05). No significant correlation, however, was found between Group 2’s summarization performance and Information (r = .38, p = .109). The results suggest that in general, the intermediate student interpreters who could comprehend and recall the SL information in a more cost-effective way tended to interpret better, just as it was found in the beginner student interpreters. In comparison with the beginner student interpreters, how efficiently the intermediate student interpreters comprehend and recall the SL information did not seem to have an obvious relation with one specific respect in their interpreting performance, that is, information accuracy and completeness. Scoring of post-interpreting summarization. The scoring of postinterpreting summarization focused on two issues: (1) how accurately and completely the critical SL messages are reformulated in the summary (2) how logically the summarized messages are presented in the summary . Two English teachers (at the same university as the participants) independently rated all the 81 participants’ summaries. They discussed until they attained a consensus whenever they had different opinions about rating. Each student interpreter’s final mark in summarization was the average of the marks provided by the two raters (inter-rater coefficient r = .93). In summarization, nine points was the full mark since there were in total nine pieces of critical SL information. 4.2.2 Explanatory power of summarization performance on interpreting performance 4. RESULTS Data from the 81 participants were analyzed with the software R [17]. M ost of the comparisons were implemented with nonparametric analyses due to the unbalanced sample sizes between the two groups. One exception lies in the comparison of overall interpreting performance between the two groups (in which t-test was conducted), given that the two data sets were found normally distributed. The effect size r of statistic U in M ann-Whitney U test was calculated with rcompanion package [12] and the effect size of t values was computed with effsize package [18]. As summarization performance was significantly correlated with interpreting performance, a question is raised whether the performance in such a typical and frequently-used interpreting training exercise can explain or contribute to student interpreters’ interpreting performance. To answer this question, the present study conducted a series of linear regression analyses with the data from either group, in which the dependent variable was the interpreting performance (Overall Score and the two sub-scores) and the main independent variable was the summarization score (Table 2). Theoretically, the participants’ proficiency in either the SL or the TL can relate to their interpreting performance [2] and summarization performance, but in the current regressions only the potential moderating effect of the SL proficiency was controlled statistically. The major rationale is that in the current English-to-Chinese CI task, both the interpreting performance and the summarization performance related to the participants’ English proficiency (i.e., the SL proficiency) more than they related to their Chinese proficiency (i.e., the TL proficiency). Based on the results of two national English proficiency tests for English-majored university students in China [8,20], the participants’ English proficiency probably varied among them, but their Chinese proficiency would not since they were all native speakers in this language and had all passed a competitive entrance examination in which Chinese was a core subject before enrolled in the current interpreting programme. In the regression, the participants’ English proficiency was indicated by their scores in an English verbal fluency test, in which they were asked to produce as many English words as possible in accordance with the category presented (e.g., jobs, sports) in 60 seconds. The verbal fluency so measured is considered a strong indicator of vocabulary size [1], which forms an important part of language proficiency. 4.1 Performance in Summarization and in Interpreting As demonstrated in Table 1, Group 1’s performance in postinterpreting summarization was rated 2.20 (SD = 1.16) on average, which was not significantly different from Group 2’s, which was rated 2.29 (SD = .92) on average (U = 518.50, p = .43). On the other hand, Group 2’s overall score in interpreting (“Overall Score” hereafter) (M ean = 82.00, SD = 5.16) was significantly higher than Group 1’s (M ean = 66.24, SD = 13.55), t (75) = -7.55, p = .000 < .01). Similarly, significant differences were found in the two sub-scores of interpreting performance between the two groups (i.e., Information and TL expressions, see Table 1 for details). These results show that the student interpreters who had been trained for a longer period of time achieved better interpreting performance (both in Overall Score and in terms of each sub-score). Nonetheless, the student interpreters who had received more interpreting training did not show significant difference in summarization performance from those who had not received so much interpreting training. 4.2 Relationship between Summarization and Interpreting 4.2.1 Correlation Results show that when the potential moderating effect of SL proficiency was controlled, Group 1’s summarization score significantly explained 25% variance in the students’ Overall Score (ΔR² = .25 = .25 × 100% = 25%, ΔF = 24.85, p = .000 The correlation between Group 1’s summarization performance and Overall Score was found significantly positive (r = .60, p = .000 < .01). Positive and significant correlations were also 90 Table 2. Explanatory power/contribution of summarization performance on interpreting performance, with the potential effect of English proficiency controlled statistically (N = 62 in Group 1; N = 19 in Group 2) Regression Dependent variable Independent variable Group ΔR² F β 1 1 0.25 24.85*** 6.07 Overall Score 2 2 0.14 4.48? 2.12 3 1 0.23 20.58*** 4.18 summarization Information 4 performance 2 0.09 2.21 .93 5 1 0.21 18.86*** 1.89 TL expressions 6 2 0.20 6.06* 1.15 Note. ***: p < .001; *: .01 ≤ p < .05; ?: .05 ≤ p < .10. for/contribute no less than 20% variance in their interpreting < .001), 23% variance in Information, and 21% variance in TL performance. These results indicate that to student interpreters expressions (see Table 3 for details). M eanwhile, the explanatory (especially at the beginning stage of interpreting training), those power of Group 2’s summarization score on their interpreting who are more efficient in comprehending and recalling the SL performance was marginally significant (ΔR² = .14 = .14 × 100% Table 1. S tudent interpreters’ summarization performance and interpreting performance at two stages summarization performance Information TL expressions interpreting performance Overall Score Group 1 (N=62) M ean SD 2.20 1.16 41.99 9.90 24.24 4.60 66.24 13.55 Group 2 (N=19) M ean SD 2.29 0.92 53.16 2.85 29.18 2.34 82.00 5.16 U/t effect size† 518.50 158.50*** 200.00*** -7.55*** r= .09 r= 0.53 r= 0.48 Cohen’s d = -1.30 Note. ***: p < .001. † : The effect size r ranges from -1.00 to 1.00, with .10 being the threshold for a small effect, .30 for a moderate effect, and .50 for a large effect [4]. In t-test, the effect size of statistic t (Cohen’s d) ranges from .01 to 2.00, with .20 being the threshold for a small effect, .50 for a moderate effect, and .80 for a large effect [3]. = 14%, ΔF = 4.48, p = .050) and the explanatory power on Information was not significant (ΔF = 2.21, p = .157). By contrast, Group 2’s summarization score was found to significantly and positively explain 20% variance in TL expressions (ΔR² = .20 = .20 × 100% = 20%, ΔF = 6.06, p = .026 < .05). messages are more likely to perform better in interpreting. Given that both groups’ summarization performance were reported to have significant and positive correlations with the TL grammaticality and appropriateness, the results suggest that how students comprehend and recall the SL information plays an important role in the quality of their interpreting output. To interpreting instructors, these results indicate that if we aim at improving students’ interpreting performance, we can develop and integrate into our online interpreting training systems more summarization exercises that combine both on-line and off-line resources, as well as providing a proper amount of memory practice such as retrieval exercises that can improve trainees’ summarizing ability [10,19]. 5. DISCUSSION The present cross-sectional study invited 62 beginner student interpreters and 19 intermediate student interpreters, examining and comparing their performance in post-interpreting summarization and their interpreting performance. With a series of quantitative analyses, three major findings were attained. First, the intermediate student interpreters achieved better interpreting performance (both in the overall performance and in terms of two specific aspects of interpreting performance) than the beginner student interpreters did. Nonetheless, the former group, who had been trained in interpreting for a longer period of time, was not found significantly different from the latter group in summarization performance. The significant differences in interpreting performance between the two groups found in the current study are consistent with one’s intuition since the former group received more interpreting training and were thus supposed to be more competent in interpreting. With respect to the summarization performance, the results did not support the conclusion in [5] that the more interpreting experience one had, the less efficient one became in recalling the SL input. These results suggest that as the CI training proceeded, the current student interpreters’ efficiency in recalling SL information may gradually lose its close relation with their interpreting (training) experience. This may be due to the fact that interpreting training programmes (either delivered in a traditional way or in a distance/e-training way) usually focus on interpreting skills rather than on language proficiency or language-learning drills, while language proficiency is an essential support of summarization quality. M eanwhile, Group 1’s summarization performance was found closely related to their interpreting performance in information accuracy and completeness and also to their performance in the TL grammaticality and appropriateness (underpinned by the significant correlations and the significant explanatory power reported above), while in Group 2 similar close relationship was found only between their summarization performance and the performance in the TL grammaticality and appropriateness, but not between their summarization performance and the performance in information accuracy and completeness. The results show that student interpreters’ efficiency in recalling the SL input may not change even when their interpreting performance in information accuracy and completeness significantly improved. Further research is thus needed to scrutinize what factor, if it is not efficiency in the recall of SL messages, may have played a more critical role in helping student interpreters render SL messages accurately and completely. 6. CONCLUSIONS The present study mainly investigated student interpreters’ performance in CI and in post-interpreting summarization at different stages of interpreting training (beginner and intermediate). When doing so, the current study also examined the relationship between summarization performance and CI performance. The results showed that although the student interpreters who received more interpreting training were more Another finding is that both groups’ summarization performance had significant positive correlations with their overall interpreting performance. Besides, their summarization performance (in particular Group 1’s) was found to significantly account 91 likely to achieve better interpreting performance, they may not differ significantly from those with less interpreting training experience in the sense of summarization. With respect to the relation between summarization performance and CI performance, the results demonstrated that the two performances were significantly and positively related to each other for both the beginner student interpreters and the intermediate ones. Besides, summarization performance made positive contribution to CI performance (especially for beginner student interpreters). Pedagogically, these results suggest that summarization exercises have a potential positive effect on interpreting performance, and thus more finely-designed summarization exercises and related quiz items can be introduced into distance or e-interpreting training. Internet- or corpora-based platforms for interpreting training can make full use of the rich and most updated interpreting materials online when developing summarization exercises of various topics and of different difficulty levels so that the exercises can better meet the needs of students of different interpreting competence levels and better serve different training purposes. M oreover, training platforms empowered by technologies like Big Data and artificial intelligence can provide immediate feedback on students’ summaries as well as advice for further exercises, which helps students become more selfmotivated in the future interpreting training. By so practising summarization via distance or e-interpreting-training programmes, student interpreters are more likely to achieve better interpreting performance with an increased sense of achievement. [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12] [13] [14] 7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author is grateful to Prof. Yanping Dong from Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (GDUFS) for her supervision to the current research. The author also thanks members from Bilingual Cognition and Development Lab, GDUFS for their assistance in data collection. Besides, the author thanks the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful suggestions. The research was supported by a grant (BCD201702) from Bilingual Cognition and Development Lab, GDUFS, a grant (290-XGS17023) directly from GDUFS, and a grant (GD18YWW02) from Guangdong Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Science. [15] [16] 8. REFERENCES [1] Bialystok, E. 2009. Bilingualism: The good, the bad, and the indifferent. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. 12,1 (Jan. 2009), 3-11. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728908003477 [2] Cai, R., Dong, Y., Zhao, N., and Lin, J. 2015. Factors contributing to individual differences in the development of consecutive interpreting competence for beginner student interpreters. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer. 9, 1 (M ar. 2015), 104-120. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1080/1750399X.2015.1016279 [3] Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Edition). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, M ahwah. [4] Cohen, J. 1992. A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 112, 1 (Jul. 1992), 155-159. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1037/00332909.112.1.155 [5] Darò, V. and Fabbro, F. 1994. Verbal memory during simultaneous interpretation: Effects of phonological [17] [18] [19] [20] 92 interference. Applied Linguistics. 15, 4 (Dec. 1994), 365-381. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/15.4.365 Fantinuoli, C. 2017. Computer-assisted preparation in conference interpreting. Translation & Interpreting. 9, 2, 2437. DOI= https://doi.org/10.12807/ti.109202.2017.a02 Fantinuoli, C. 2018. Computer-assisted interpreting: challenges and future perspectives. In Trends in E-Tools and Resources for Translators and Interpreters, G. C. Pastor and I. Durán-M uñoz Eds. Brill | Rodopi, Leiden, 153-174. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004351790_009 Jin, Y. and Fan, J. 2011. Test for English M ajors (TEM ) in China. Language Testing. 28, 4 (Oct. 2011), 589-596. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532211414852 Jones, R. 2014. Conference Interpreting Explained. Routledge, New York, NY. Karpicke, D. and Roediger, L. 2008. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science. 319, 5865 (Feb. 2008), 966968. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1152408 Ko, L. and Chen, S. 2011. Online-interpreting in synchronous cyber classrooms. Babel. 57, 2 (Jul. 2011), 123143. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.57.2.01ko M angiafico, S. 2016. Summary and Analysis of Extension Program Evaluation in R, Version 1.15.0. URL https://rcompanion.org/handbook/ M ayor, B. and Ivars, J. 2007. E-Learning for interpreting. Babel. 53, 4 (M ay 2008), 292-302. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1075/babel.53.4.01may M orales, J., Padilla, F., Gomez-Ariza, J., and Bajo, T. 2015a. Simultaneous interpretation selectively influences working memory and attentional networks. Acta Psychologica. (Amst.) 155 (Feb. 2015), 82-91. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2014.12.004 M orales, J., Yudes, C., Gomez-Ariza, J., and Bajo, T., 2015b. Bilingualism modulates dual mechanisms of cognitive control: evidence from ERPs. Neuropsychologia. 66 (Jan. 2015), 157-169. DOI= https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.11.014 Niedzielski, H. and Kummer, M . 1989. Learning translating and interpreting through interlanguage. In Translator and Interpreter Training and Foreign Language Pedagogy, P. W. Krawutschke Ed. State University of New York at Binghamton, New York, NY., 132-146. R Core Team. 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.Rproject.org/ Torchiano, M . 2018. Effsize: Efficient Effect Size Computation. DOI= https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1480624 Zhou, A., M a, X., Li, J., and Cui, D. 2013. The advantage effect of retrieval practice on memory retention and transfer: Basedon explanation of cognitive load theory. Acta Psychologica Sinica. 45, 8 (Aug. 2013), 849-859. DOI= https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2013.00849 Zou, S. and W. Chen. 2010. TEM Tests: Past, Present and Future [in Chinese]. Foreign Language World. 30, 6(Dec. 2010): 9-17.