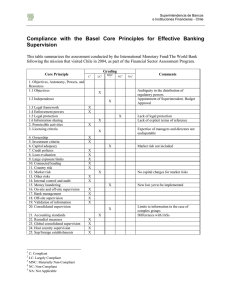

Institutional structure of financial regulation an

Anuncio