The Nightingale and the Rose, The Devoted Friend; Oscar Wilde

Anuncio

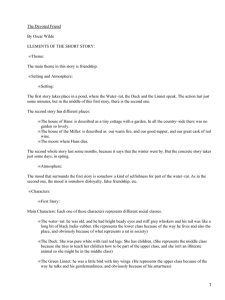

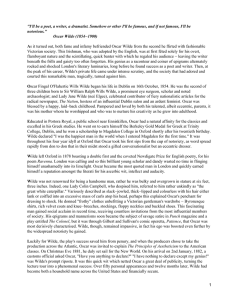

BIOGRAPHY Birth name: Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde Birth date: October 16, 1854 Death date: November 30, 1900 Parents: Sir William Wilde and Jane Francesca Elgee Siblings: (full) William and Isola; (half) Henry, Emily and Mary By the time William Wilde was 28, he had graduated as a doctor, written two books and been appointed medical advisor to the Irish Census of 1841. When the medical statistics were published two years later they contained data which had not being collected in any other country at the time, and as result William opened a Dublin practise specializing in ear and eye diseases, he felt he should make some provision for the free treatment of the city's poor. In 1844, he founded St. Mark's Ophthalmic Hospital, built entirely at his own expense. Before he married, William fathered three children. Henry Wilson was born in 1838, Emily in 1847 and Mary in 1849. Sadly, Mary and Emily, who were raised by William's brother, both died in a fire at the ages of 22 and 24. Oscar's mother, Jane Francesca Elgee, first gained attention in 1846 when she began writing revolutionary poems under the pseudonym Speranza for a weekly Irish newspaper, The Nation. In 1848, as the country's famine worsened and the Year of Revolution took hold of Europe, the newspaper offices were raided and had to close. Jane's first child, William Willie Charles Kingsbury, was born on September 26, 1852 and her second, Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie, on October 16, 1854. The daughter she had longed for, Isola Emily Francesca, was delivered on April 2, 1857. Ten years later, however, Emily died from sudden fever. Oscar was profoundly affected by loss of his sister, and for his lifetime he carried a lock of her hair sealed in a decorated envelope. Aesthete, wit and dramatist, Oscar Wilde was born at 21 Westland Row, Dublin. He was raised in a mansion at I Merrion Square in an atmosphere of upper−middle−class comfort, culture, and social scandal (due to his mother's pronounced nationalist leanings and his father's much−publicized affair with a female patient). Oscar followed his elder brother William to school at Portora Royal School at Enniskillen, and proceeded to Trinity College in Dublin, in 1872. There his academic and literary talents were cultivated by the Anglo−Irish 1 classicist and Kant scholar John Pentland Mahaffy, whose Social Life in Greece (1874), containing the first frank discussion of Greek homosexuality in English, appeared with a preface acknowledging Wilde's help throughout. In his second college year Wilde won the Berkeley Gold Medal for Greek and, deciding to continue his studies at Oxford, matriculated at Magdalen with a classical scholarship in 1874. In 1878 he won the Newdigate Prize for Poetry with Ravenna and graduated with a double first, narrowly missing a college Fellowship in 1879. At Oxford his chief mentor was Walter Pater, whose Studies in the History of the Renaissance (1873) served as a gospel for the aesthetic movement. Strongly influenced by John Ruskin, Wilde passed his Oxford years in an atmosphere where his intellectual and aesthetic interests and the conflicting claims of homo− and heterosexuality, and Catholicism competed for his attention. Just such an intoxicating mixture of ecstasy and abasement characterizes his first book, Poems (1881), which, through stylistically saturated with the mood of fin de siècle aestheticism, hints already at the themes of homosexuality, individualism, and Republican indifference to authority. In 1879 Wilde set up in London as a self−styled `Professor of Aesthetics'. So considerable was the impact of his self−promotion that he was engaged to undertake a lengthy lecture tour of North America during 1882. Although Wilde developed his public image considerably in this period, it was also a time when he consolidated the ideas which were to underpin the critique of late Victorian social and political conventions in his best satirical writings, soon to follow. For eighteen months he edited The Woman's World (in 1887−1889), soliciting contributions from society ladies including his mother and wife, Constance Lloyd, a Dubliner whom he had married in 1884 and with whom he had two sons, Cyril and Vyvyan, born in 1885 and 1886. Together they made their Chelsea home at 16 Tite St. into the `House Beautiful'. From 1886 Wilde had been having sexual relationships with men, beginning with Robert Ross, a Cambridge undergraduate who was to remain a faithful friend and ultimately to become his literary executor. In 1891 he met Lord Alfred Douglas, a petulant and beautiful young man sixteen years his junior, who temporarily displaced Ross as his lovers. At the same time, his writing began to deal more explicitly with homosexual themes. Wilde liberationist outlook was further developed in The Soul of Man Under Socialism (1891). Thereafter Wilde concentrated on three matters: the perpetuation of his stage success with A Woman of No Importance (1893), An Ideal husband, and The Importance of Being Earnest (both produced in 1895); a life of self−indulgence in London, Paris, Monte Carlo, and at the English and French resorts, principally in company with Douglas; and a series of melodramatic works of a quasi−religious nature. In all his writings of the 1890s, Wilde was preoccupied with emotional and psychic themes that seem to reflect childhood anxieties: parents who have lost their children, children who have lost their parents, people who are not what they seem; the inevitability of tragedy; Puritanism, philanthropy and hypocrisy. In 1895, as Wilde was enjoying the success of The Importance of Being Earnest, he allowed himself to be lured into instigating an action for criminal libel against Douglas's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, who had objected strenuously to their relationship and had left a card in the Albemarle Club inscribed `To Oscar Wilde, posing as a somdomite'. Forced to abandon the prosecution under cross−examination by Edward Carson, Wilde in turn was charged with gross indecency under the Criminal Law Amendment Act (1886), convicted by jury on 25 May 1895, and sentenced to two years' penal servitude with hard labour. Towards the end of his imprisonment at Reading, Wilde wrote an account of his relationship with Alfred Douglas in the form of a self exculpatory letter addressed to him, and first published by Ross in abridge form as De Profundis (1905). After his release in1897, Wilde immediately left England and, bankrupt and homeless, drifted aimlessly around France and Italy, sometimes with Douglas, sometimes with Ross, using the 2 pseudonym `Sebastian Melmoth'. Writing nothing other than The Ballad of Reading Gaol, he indulged heavily in drink and sex. Wilde died at the Hôtel d'Alsace in Paris on 30 November 1900, most likely of meningitis, and was buried in the cemetery at Bagneux. Later his body was reinterred at Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, under a large monument by Jacob Epstein. OSCAR WILDE'S AESTHETICS Ruskin, Pater, Morris, Swinburne and Whistler were Oscar's teachers. From them, he took some aesthetic concepts. Wilde appropriates two attitudes: the moralizing aestheticism and the art for art's sake, although in his time the second attitude is the predominant one with the French symbolists' influence, and also with the Goethe of the feeling of fleetingness of time that makes the artist cling to the moment. In fiction, Wilde dealt with some characteristics that appeared in every story he wrote: the action will develop in the heart and in the typical areas of the English high society; the characters are prototypes −aristocrats, students, artists, wealthy people− of the social classes to which they belong, more as generic masks than a portrait of the specific person, because a mask is more eloquent than a face; formal elements: causality, occurrence, secret and irony. He also uses in his tales some symbolic elements, such as the numbers three and seven (that are said to have biblical symbolism). Occasionally, the short stories muse got to Wilde at his children's bedside, whom he used to tell beautiful tales before sleeping. In other occasions, he created short stories as an example of his statements or as a sample of his brilliant inventiveness. Wilde did not talk: he told []. He told slowly; his own voice was wonderful. The writer gathered together in three collections the tales that he had published in several magazines: The Happy Prince and other tales, 1988 (The Happy Prince, The Nightingale and the Rose, The Selfish Giant, The Devoted Friend and The Remarkable Rocket) ; A House of Pomegranates, 1891 (The Young King, The Birthday of the Infanta, The Fisherman and his Soul and The Star−Child); Lord Savile's Crime and other stories, 1891(Lord Arthur Savile's Crime, The Sphinx without a secret, The Canterville Ghost and The Model Millionaire). Now, I am going to deal with two short stories from his first collection The Happy Prince and other tales, The Nightingale and the Rose (1888) and The Devoted Friend (1888). I will talk about each book separately, and then I will compare them, stressing the similarities and differences I find between the two stories. THE NIGHTINGALE AND THE ROSE • Summary The Nightingale and the Rose is a story in which the first character that appears is a Student. This boy is sad because a girl promised to dance with him on condition that he brought her red roses, but he did not find any red rose; there were white roses and yellow roses, but he could not find red roses. While he was moaning because her love would not dance with him, four characters from nature started to talk about him. A little Green Lizard, a Butterfly and a Daisy asked why he was weeping, and the Nightingale said that he was weeping for a red rose. The first three characters said that weeping for a red rose was ridiculous. The Nightingale, who understood the Student, started to fly until she saw a Rose−tree. She told him to give her a red rose, and she promised, in exchange, to sing her sweetest song, but the Rose−tree told her that his roses were white, and he send the Nightingale to his brother that grew round the old sun−dial. The Nightingale went to see this new Rose−tree, and after promising the same in exchange for a red rose, the Rose−tree told her that his roses were yellow, but he send the Nightingale to his brother, who grew beneath the Student's window, so the Nightingale went there, and when she arrived, she asked the Rose−tree to give her a red rose. The Rose−tree said that his roses were red, but that the winter had chilled his veins and the frost had nipped his buds, so he could not give her a red rose. The Rose−tree gave her a solution: he told her that if she wanted a 3 red rose, she had to build it out of music by moonlight and stain it with her own heart's blood. She had to sing to the Rose−tree with her breast against a thorn; the thorn would pierce her heart and her life−blood would flow into the Rose−tree veins. The Nightingale said that death was a great price to pay for a red rose, but at the end, she accepted. The Nightingale went to see the Student and told him that he would have his red rose, that it was her who was going to build it up with her own blood; the only thing she asked him for in return was to being a true lover. Although the Student looked at her, he could not understand anything because he only understood the things that were written down in books. But the Oak−tree understood and became sad because he was fond of the Nightingale, and asked her to sing the last song and when she finished, the Student thought that the Nightingale had form, but no feeling. At night, the Nightingale went to the Rose−tree and set her breast against the thorn. She sang all night long. She pressed closer and closer against the thorn until the thorn finally touched her heart and she felt a fierce pang of pain. The more the rose got the red colour, the fainter the Nightingale's voice became, and after beating her wings, she died. The rose was finished, but she could not see it. The next morning, the Student saw the wonderful rose under his window. He took it and went to see the girl and offered her the rose, but she just say that the rose would not go with her dress and that the Chamberlain's nephew had sent her real jewels and that everybody knew that jewels cost far more than flowers. After arguing with her, the Student threw the rose into a gutter, where a cart−wheel went into it, and he said that Love was a silly thing and that he preferred Logic and Philosophy. • Characters The Student is the first character in the story. He is a boy who dreams of dancing with the girl he loves, but he is worried because he does not have a red rose, that that was what the girl asked for in return of dancing with him. He dedicates his life to books: he likes Philosophy, and he considers books the only useful thing in life. We have an example of this when the Nightingale tells him that he is going to have his rose: The Student looked up from the grass, and listened, but he could not understand what the Nightingale was saying to him, for he only knew the things that are written down in books. The three next characters could go together: the little Green Lizard, the Butterfly and the Daisy. They are all personified elements of nature. They think that it is ridiculous to weep for a red rose, and the Green Lizard even laughed outright. The next character is our protagonist. The Nightingale is all goodness. She thinks that the most important thing in the world is love, and she even gives her life for love. The three next characters could go together too. The three Rose−trees, although the important one is the one who has the red rose. He tells the Nightingale to die for a red rose. The last character is the daughter of the Professor, the girl the Student loved. She makes much of material things and she looked down on the rose the Student gave her just because it had less material value than the jewels another boy sent her. • Time and Space The action takes place in the room of the Student, when he is reading at the end of the story; in the garden that is near the Student's room's window, where we find the Rose−tree that has the red rose and where the Nightingale knows about the problem the Student has and the last places is the daughter of the Professor's house, where she despises the Student and his rose. We can easily see in the story that the action develops in some hours. The evening and the night of one day, when the Nightingale listens to the laments of the Student, when he find the Rose−tree that can give her a red rose and when she dies building the red rose for the Student; the other period of time is the next morning, when the Student goes to talk to the girl he loves. In the story we do not see any flashback, we see a liner 4 account. • Style The main words in this tale belong to the semantic fields of nature, knowledge and love. We are going to see different examples of this. We see the semantic field of nature in asked a little Green Lizard.., said a Butterfly, whispered a Daisy, He is weeping for a red rose −said the Nightingale, She passed through the grove, In the centre of the grass−plot was standing a beautiful Rose−tree, But the Oak−tree understood, etc. The semantic field of knowledge can be seen in cried the young Student, Ah, on what little things does happiness depend! I have read all that the wise men have written, and all the secrets of philosophy are mine, yet for want of a red rose is my life made wretched, It is not half as useful as Logic, for it does not prove anything, and it is always telling one of things that are not going to happen, and making one believe things that are not true [] I shall go back to Philosophy and study Metaphysics. The Semantic field of love is present in these examples: Here at last is a true lover, Surely Love is a wonderful thing, Yet Love is better than Life, and what is the heart of a bird compared to the heart of a man?, All that I ask of you in return is that you will be a true lover, for Love is wiser than Philosophy, though she is wise, and mightier than Power, though he is mighty, She sang first of the birth of love in the heart of a boy and a girl. Apart from these semantic fields, we can find some stylistic resources such as comparison, that is the most resorted stylistic characteristic: His hair is dark as the hyacinth−blossom, and his lips are red as the rose of his desire; but passion has made his face like pale ivory, It is more precious than emeralds, and dearer than fine opals, My roses are white, as white as the foam of the sea, and whiter than the snows upon the mountains, My roses are yellow, as yellow as the hair of the mermaiden [] and yellower than the daffodil that blows in the meadow [], And a delicate flush of pink came into the leaves of the rose, like the flush in the face of the bridegroom when he kisses the lips of the bride. Another stylistic resource is personification. We can see that the main characters, apart from the Student, are animals or elements from nature, such as a little Green Lizard, a Daisy, a Butterfly, a Nightingale, a Rose−tree and an Oak−tree. • Other outstanding features One remarkable thing is that at the end of the tale, when the Student says that the daughter of the Professor is ungrateful, we can see that the really ungrateful one is the Student himself, who look down on the Nightingale's life. We can see that the most important theme in this tale is beauty, it is everything for the artist who gives her life for it, and the less important thing for her is materialism, represented by the Student and also by the daughter of the Professor. The Nightingale sacrifices her life to create the rose that will give love to the Student. The bird is very ancient as a symbol in the cultural tradition. The bird is the symbol of immaterial beauty, and the election of a nightingale in this story has a deeper meaning: this is a lonely and shy bird. Our Nightingales is able to die in exchange for eternal love: Love, in our story is represented by the Rose, that is the most perfect flower in the world: And the marvellous rose became crimson, like the rose of the eastern sky. Crimson was the girdle of petals, and crimson as a ruby was the heart, Here is a red rose! I have never seen any rose like it in all my life. It is so beautiful that I am sure it has a long Latin name. 5 We can also see in this tale some elements I listed before, such as prototypical characters (the Student), or the number three (the Nightingale goes to three Rose−tree to find the red rose, and the characters that are with the Nightingale while the Student is moaning, are three: the Green Lizard, the Butterfly and the Daisy). THE DEVOTED FRIEND • Summary The story starts in a pond, where some little ducks were swimming. Their mother, the Duck, was telling them that they would not be in the best society unless they could stand on their heads, but the little ducks did not pay attention. The Water−rat said that they were very disobedient, and the Duck told him that parents should be patient with children. The Water−rat answered that he had no children, that he wan not even married, he preferred friendship than love. A Green Linnet that was there asked what were the duties of a devoted friend, and started to tell the story of The Devoted Friend. Hans was a man with a kind heart. He lived in a tiny cottage alone and everyday he worked in his garden. Hans had many friends, but the best one was Hugh the Miller. Hugh always talked about how important is friendship and share everything with one's friends, but he never gave anything to Hans. Hans always worked in his garden, but in winter he felt lonely and lived in bad conditions because of the cold weather, and throughout the winter, Hugh never visited him. Hugh's wife told him that it was better to leave alone the people that were living in bad conditions, because if they went to see him, they would just bother Hans. So, Hugh waited the Spring to go to see Hans, and while he was at it, Hans would give him a large basket of primroses because it would make him (Hans) so happy. When Hugh arrived at Hans' house, Hans told him that he would bring all the primroses into the market and sell them to buy a new wheelbarrow, because throughout the winter he had to sell his, because he needed the money to eat. The Miller told Hans that he would give him his wheelbarrow, although it was not in good repair, he was very generous and he would give it to him because he had a new one for himself. Hans said that he could repair the wheelbarrow because he had a plank of wood. When Hugh listened to these words, he asked Hans to give him the plank of wood because he needed it and he told Hans that he should give him that because he was going to give him the wheelbarrow. The Miller also asked Hans to give him some flowers because he deserved them because he was going to give him the wheelbarrow. The next day, The Miller asked Hans to bring a sack of flour for him to the market, and he should do it because he was going to give him his wheelbarrow, but Hans was happy of helping The Miller because he was his friend. The following day, Hugh was to ask Hans to mend his barn−roof for him, and Hans should do it because he was going to give him the wheelbarrow. The next day, Hans drove The Miller's sheep to the mountain because the Miller was going to give him his wheelbarrow. While Hans worked for The Miller, The Miller said beautiful things about friendship. One night, The Millar went to see Hans with a lantern and a big stick because his son has fallen off a ladder and he wanted Hans to go to call the Doctor. It was dark, and Hans asked The Miller to give him the lantern, but The Miller told him that it was new and he did not want that anything happened to it. So Hans went to see the Doctor. The Doctor went in his horse, and little Hans went alone, without seeing because of the darkness, and he fell into a hole and he drowned. In the funeral, The Miller had the best place, because he was his best friend. After the funeral, The Miller said that Hans was a great loss for him because he was going to give him his wheelbarrow, and then, he did not know what to do with it, and that it was in such bad repair that he would not get anything for it if he sold it. The Water−rat did not understood the story and he did not like that the story had a moral and he said Pooh and went back to his hole. The Linnet asked the Duck what she thought about the story, and the Duck said that it is very dangerous to tell a story with a moral. At the end, the author speaks himself and say that he agree with her. • Characters 6 We have two stories in this tale, so he have characters form one and from the other story. The first characters that appear are three animals. The Water−rat, the Duck and the Linnet. We can see here that Oscar Wilde builds up his story with simple, conflicting and symbolic characters. We can see this characters as the representation of different social classes: the Water−rat represents the lower class (aquatic underworld), the Duck represents the middle class (surface) and the Linnet the upper class (air). We see an example of social hierarchy in You will never be in the best society unless you can stand on your heads, that is the first sentence the Duck says to her children. In the second story, that that the Linnet tells, The Devoted Friend itself, has main and secondary characters. Hans is the main character. A man who really practices friendship. He loves his garden, but his friendship with Hugh the Miller is above all. He has many friends, but when he needs them, they do not help him. The other main character is Hugh the Miller, a man who says a lot of beautiful things about friendship but he does not act as a devoted friend. He says things like Real friends should have everything in common, or I think that generosity is the essence of friendship. The secondary characters are the Miller's Wife, the Miller's son, the Doctor and the Blacksmith. The Miller's Wife is always saying that her husband is the best friend in the world and the most generous man. The Miller's son just asks why they don't bring Hans to live with them in the winter, to what his father asks saying that if Hans would see what they have in their house, he might get envious, and envy is the most terrible thing, and that could change people personality, and he would not allow Hans to led to any temptations. The Doctor appears at the end of the second story; he is the one that is going to heal the Miller's son. The last character is the Blacksmith; he is who starts the conversation after Hans funeral, saying that Hans is a great loss. • Time and Space The first story takes place in a pond, where the Water−rat, the Duck and the Linnet speak. The action last just some minutes (the time that the Linnet uses in telling the story), but in the middle of this first story, we find the second one. The second story has different places. The house of Hans, that is described as a tiny cottage with a garden, In all the country−side there was no garden so lovely. Another important place in this story is the house of the Miller. We find a description of it made by the owners our warm fire, and our good supper, and our great cask of red wine. Another important place for the development of the action are the moors where Hans dies. There are also a description of them and the weather: The night was so black that little Hans could hardly see, and the wind was so strong that he could scarcely stand, But the storm grew worse and worse, and the rain fell in torrents, and little Hans could not see where he was going, or keep up with the horse. At last he lost his way, and wandered off on the moor, which was a very dangerous place, as it was full of deep holes. The second whole story last some months, because we have to notice that we are said that the winter went by. But the concrete story takes just some days, in spring. We notices this because throughout the story we see temporal marks such as The next day, Early the next morning , etc. We have in this tale a linear account marked by these temporal particles, and we do not find any flashback. At the middle of the second story, there is an interruption in which we go back to the first story (that of the animals) because the Water−rat thought that the story was finished. • Style The main words in this tale belong to the semantic fields of nature and feelings and values. Now, we are going to see different examples of this. 7 We see the semantic field of nature in The little ducks were swimming about in the pool, asked a Green Linnet, who was sitting in a willow−tree, Sweet−william grew there, and Gilly−flowers, and Shepherds'−purses, and Fairmaids of France. There were damask Roses, and yellow Roses, lilac Crocuses, and gold, purple Violets and white. The semantic field of feelings and values can be seen in Love is all very well in its way, but friendship is much higher, Lots of people act well, but very few people talk well, which shows that talking is much the more difficult thing of the two, and much the finer thing also, Well, really, that is generous of you, idleness is a great sin, and I certainly don't like any of my friends to be idle or sluggish, At present yhou have only the practice of friendship; some day you will have the theory also. Apart from these semantic fields, we can find some stylistic resources, such as personification or irony, that is present in the whole story. Personification can be seen in the story in which the main characters are animals: But the little ducks paid no attention to her, said the Water−rat, in a very angry manner. Irony is present in the whole story, and we find examples of this in Lots of people acts well, but very few people talk well, which shows that talking is much the more difficult thing of the two, and much the finer thing also, or when the Miller's Wife says How well you talk! we see that it is a stupid comment looking at the Miller's character. • Other outstanding features To start with, we must remark that, as we say that the number three is present in Oscar Wilde's stories, the characters of the first story (that of animals) are three, a Water−rat, a Green Linnet and a Duck. The Devoted Friend has the form of a reversed fable: the facts are staged by human beings, and try to give a lesson to animals. Some literary critics say that Hans could be the alter ego of Oscar Wilde because he sometimes felt exploited by his friends. This tales has a moral, but Wilde did not want to lecture anyone, and it is clearly stated at the end of the story: `I am rather afraid that I have annoyed him', answered the Linnet. `The fact is, that I told him a story with a moral' `Ah, that is always a very dangerous thing to do', said the Duck. And I quite agree with her COMPARISON BETWEEN THE TWO STORIES We can set some points in which we find similarities between the two stories. One of these points is what I have described as a typical feature in Oscar Wilde's writings: the number three. As I said before, in both tales the number three is present: in The Nightingale and the Rose three are the Rose−trees that our main character visited, and in The Devoted Friend three are the animals that appear in the first story. Another feature that I talked about was the simplicity of the characters, and that in the same story we find conflicting characters. In The Nightingale and the Rose, our characters have no name, they are just the Student, the Nightingale, etc., and these two characters are in complete opposition: the first one represents materialism and the second one represents ethereal beauty. In The Devoted Friend, we find simple names for our characters Hans and Hugh the Miller, and we also find characters with no name, such as the Duck, the Green Linnet or the Water−rat. Here, we have characters in complete opposition too: In the first story we have The Duck and The Linnet, who are against the Rat (the first ones defend love, and the last one defends friendship), and in the second story, Hans and Hugh have different conceptions of friendship, or, at least, they act in a very different way. 8 Another common thing of the two tales is that, in both of them, there are animals. In The Nightingale and the Rose all the characters are animals except the Student and the daughter of the Professor. In The Devoted Friend, the first story is made up of animals, only animals, and the second story is made up of human beings, only human beings. In both stories, feelings are treated: in The Nightingale and the Rose the main theme is Love, whereas in The Devoted Friend the main theme is Friendship. And, although apparently, the only story that has a moral is The Devoted Friend because the word moral appears written down in the paper, we can say that The Nightingale and the Rose has a moral too: we should appreciate everything, even the most insignificant thing, not only those thing of which we know their price, because in the smallest thing we can find the bigger one. But each one can have his own interpretation. PERSONAL OPINON I chose these two stories due to different reasons. I decided, firstly, to talk about The Nightingale and the Rose because when I read it I thought it was a beautiful story, although it was very sad too. I also thought that it was teaching the reader a lesson, so I considered that it was a nice tale to include in my work. Secondly, I decided to add one more tale to my work because I thought it would be interesting to compare two different tales of the same author. I chose The Devoted Friend because it had a different structure from The Nightingale and the Rose: it was made up of two stories, with different characters. But I also chose it because it had many similarities with The Nightingale and the Rose, all the similarities that I tried to explain above. And I also chose The Devoted Friend because it was a sad story and had an explicit moral. I noticed that in the two tales, the good characters die. I think it is curious that in both stories the good characters end badly, and the reason of their death in both cases is having a kind heart and helping the others, and curiously too, these others do not appreciate this help. I have read that this disloyalty in The Devoted Friend and the sad events in both stories could be a reflection of Oscar Wilde's feelings and life, so, in this case, it is understandable the pessimism of both tales. BLIBLIOGRAPHY Official Web Site of Oscar Wilde, www.cmgww.com/historic/wilde WELCH, ROBERT. The Oxford Companion to Irish Literature. Oxford Clarendon Press, 1996. WILDE, OSCAR. Complete Shorter Fiction, edited with an introduction by Isobel Murray. Oxford [etc.] Oxford University Press, 1980. WILDE, OSCAR. Cuentos; introducción y notas de Antonia González López. Fuenlabrada (Madrid) Magisterio D.L., 1994. 8 9