PERUVIAN PRIMARY EDUCATION: IMPROVEMENT STILL

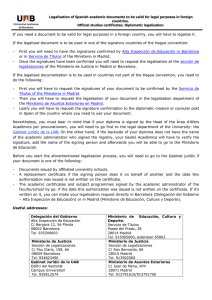

Anuncio